Northwest fossil fuel export schemes have brought a flood of coal and oil proposals to the region’s shores. But the fossil export tsunami has a third wave as well: fracked fuels, including the massive liquefied natural gas (LNG) export proposals in British Columbia, as well as several projects that would export liquid petroleum gases (LPGs) such as propane and butane.

In fact, West Coast propane exports have increased six-fold in the past year—most likely because a Canadian energy company called Petrogas recently expanded a fracked fuel export facility at Cherry Point in Whatcom County, Washington. The risks posed by this facility are a direct threat to the interests of the Lummi Nation, who have lived and fished in the area for millennia, and consider Cherry Point a site of central cultural and economic importance.

30,000 barrels of propane exported per day?

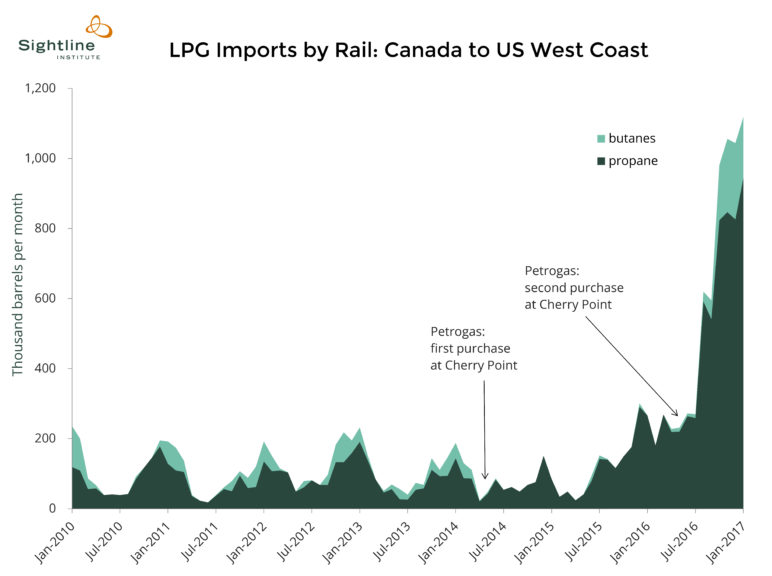

In two separate purchases—one in March 2014 and the other in September 2016—Petrogas acquired land, a pair of liquid fuel storage tanks, and a wharf capable of loading oceangoing tankers at the site of an aluminum smelter at Cherry Point, Washington. From about 2009 to 2014, the terminal averaged just two or three ships per year, or less than 5,000 barrels per day, of butane exported to Asia or Latin America. There is now compelling evidence suggesting that exports have increased six-fold, with the facility now exporting to Asia 30,000 barrels of propane per day refined from Canadian fracked gas.

The West Coast now receives more than a million barrels of propane and butane each month delivered by rail from Canada.

Petrogas has invested heavily in the project. The county has assessed the value of the site—including the smelter, which Petrogas did not purchase—at $67 million. Yet the company has spent at least $404 million on purchases and improvements for its fuel export operations alone—demonstrating both the value of grandfathered shoreline and tideland permits and the expectation of robust profits from fracked fuel exports.

Petrogas likely ships some fuel to the site via pipeline from two nearby refineries. But RBN Energy has reported that the site’s expansion relied on rail deliveries. Similarly, the US Energy Information Administration reports a dramatic rise in rail shipments of propane from Canada to the West Coast. The sudden increase in exports coincides exactly with the Petrogas takeover of the site, which remains the only large propane export site on the West Coast.

Official figures from the US Energy Department show that the West Coast now receives more than a million barrels of propane and butane each month delivered by rail from Canada. That works out to more than 30,000 barrels daily—roughly the equivalent of a mile-long train arriving every other day.

The West Coast context

With the acquisition of the Whatcom County facility, Petrogas has laid claim to the sole major propane export facility on the West Coast. Based on public statements by the project backers, Petrogas ships the propane to Japan for use in heating and petrochemical manufacturing. The company hasn’t revealed how much it is exporting from the site, but the US Department of Energy says that facilities on the US West Coast shipped 37,000 barrels per day in 2016, “nearly all” of which came from Cherry Point.

The beachhead Petrogas established at Cherry Point comes on the heels of three failed attempts by the industry to build out propane export capacity on the Columbia River. In March 2015, the Port of Longview rejected a proposal by Haven Energy to construct a propane-by-rail facility that could have moved 47,000 barrels per day. Shortly afterward, Portland blocked a propane train proposal backed by the Canadian energy giant Pembina that would have exported 37,500 barrels per day. Then in February 2016, Longview cut off talks with a company called Waterside that was planning a 75,000 barrel per day propane train site that would have been paired with a proposed small oil refinery nearby.

The industry has angled for large-scale propane export terminals in British Columbia, though none have yet materialized. The backers of Watson Island LNG, an export facility planned for a site near Prince Rupert have proposed shipping propane too. In fact, Petrogas’ Cherry Point facility seems to be a reincarnation of a failed LNG project of its two partners, Altagas, a Canadian energy transport company, and Idemitus, a Japanese energy supplier. Altagas originally planned two LNG facilities for Kitimat: Triton LNG and Douglas Channel LNG. In early 2016, however, Altagas halted development on Douglas Channel, and also put Triton on the back burner. Triton’s joint venture partner, Idemitsu, “suspended all efforts” on the project in mid-2016, though Altagas is apparently still planning to build a propane export facility on Ridley Island near Prince Rupert.

Safety not guaranteed

And it’s not just a theoretical risk: rail cars filled with propane exploded recently in the Sacramento area, New Brunswick, Alberta, and Tennessee among other places.

Propane by rail comes with some notable risks. It has a propensity for “boiling liquid expanding vapor explosions” (BLEVEs) when it is in tank cars or other above-ground pressurized storage tanks. When breached, the refrigerated tanks release a heavy vapor cloud that can spread at the mercy of the wind. “Pools of fire” caused by propane explosions can burn hot enough to cause second-degree burns a mile away.

Accident data show that the largest propane risk areas are in pressurized storage, pressurized transport, and transfer. Moreover, LPG trains bound for Cherry Point are at meaningful risk of derailment along their journey. And it’s not just a theoretical risk: rail cars filled with propane exploded recently in the Sacramento area, New Brunswick, Alberta, and Tennessee among other places.

Transferring liquid propane—from rail cars to refrigeration units, to storage tanks, and to marine vessels—creates many further opportunities for catastrophe. At each juncture, pipes can breach, valves can fail, hoses can rupture, and even a small flaw can compound into a conflagration. In 1984, a small propane pipe leak in San Juanico, Mexico set off a chain of explosions that culminated in one of the worst industrial accidents in history, a blast that flattened parts of town, killing 500 people and severely burning more than 5,000.

What’s next for Whatcom County?

The terminal owners applied for Whatcom County permits to replace equipment in 2015 and 2016. Their official documents do not indicate further expansion plans—in fact, the most recent application explicitly says that it would not increase total rail cars to the facility—but RBN Energy has reported rumors of Petrogas exploring a third tank, which would increase the site’s storage capacity to one million barrels.

Meanwhile, news reports suggest that propane demand could grow in Asia, where it can be deployed either as a heating fuel or as raw material for manufacturing petrochemicals used to make plastics. Energy analysts point to China in particular as a major destination for US exports, largely for petrochemical use.

At the same time, Whatcom County officials have enacted a moratorium on fossil fuel export development at Cherry Point while they move forward with more permanent zoning changes at the site. What happens there may well have a major impact not only on the health of Salish Sea, but also on the global trade in the fracked fuels.

Update 6/22/17: RBN Energy has a new analysis that provides a bit more information about Whatcom County’s LPG exports, calling it a 30,000 barrel per day facility. Among other things, it notes:

Generally speaking, the LPG exported out of Ferndale is produced by AltaGas and other natural gas processing plants and fractionators in western Canada, loaded onto Petrogas tankcars at Petrogas rail-loading terminals, and railed to Ferndale, where much of it is loaded onto VLGCs owned by Astomos Energy (a joint venture of Idemitsu and Mitsubishi Corp. that owns more than 20 VLGCs) destined for Japan. In short, the network functions as a sort of floating bridge that carries LPG from North America to Asia.

This article benefited from editorial review and research by Clark Williams-Derry and Tarika Powell.

[list_signup_button button_text=”Like what you|apos;re reading? Get our latest fossil fuel research right to your inbox.” selected_lists='{“Sightline Flashcards”:”Sightline Flashcards”,”Reclaiming Our Democracy”:”Reclaiming Our Democracy”,”Fighting Fossil Fuels”:”Fighting Fossil Fuels”}’ align=”center”]

Comments are closed.