Imagine two towns, both committed to helping their low-income residents but short on funding for social services. Both decide to require retailers to sell 5 or 10 percent of their wares at steeply discounted prices to families who qualify for benefits: milk, jeans, refrigerators, whatever. But they do it two different ways.

The first town flat-out forces stores to do it, giving them nothing back in exchange. The place gets a little better for the lowest-income families who qualified for the discount, but there are other unintended, but inevitable, consequences that hurt the whole community. Retail is highly competitive, so only the most profitable shops can afford to sell a share of their products at a loss. Lots of stores go out of business, and surviving stores tend to be ones with bigger markups and higher prices: Nordstrom, not Payless; Whole Foods, not Safeway. Prices for everybody not qualified for discounts go up. Even for those who receive the discounts, there are fewer places to shop and marked-down supplies are limited. The town overall becomes less prosperous.

The second town also requires “inclusionary pricing”—the same 5 or 10 percent discounts to qualifying families—but this town also compensates stores with economic benefits of comparable value: they can build a bigger shop than otherwise allowed under local laws; add profitable new ventures, such as liquor sales; dispense with expensive parking lots that were otherwise required; and win exemptions from certain taxes. In this community, retailers come out even and stay in business. The money they lose on their inclusionary sales is balanced out by gains from new benefits. Families with lower incomes shop where everyone else does, in a range of stores. Unlike the town that does not balance out the cost of its inclusionary pricing, this second town makes sure low-income families can thrive and be part of the local social fabric without shuttering stores and pushing up prices for those who don’t get the discount—keeping the whole community thriving and intact.

These hypothetical towns may strain belief. But as illustrations, they provide an apt analogy for the potential benefits and pitfalls of inclusionary zoning. Inclusionary zoning (IZ) is the same principle applied not to shopping but to housing. It requires builders to lease or sell a share of their new homes at below-market prices to families and individuals whose low incomes qualify them for it. Some communities balance out these affordability mandates while some do not—a difference that makes all the difference.

IZ done right, IZ done wrong

IZ done right—balancing new requirements with equal benefits to homebuilders, called “offsets” by urban planners—holds immense promise, because although where you shop does not matter much to how your life unfolds, where you live certainly does. Empirical research now demonstrates that among the best things society can do for families with lower incomes and wealth, and especially for their children, is to enable them to live in “high-opportunity neighborhoods”: neighborhoods with excellent public schools, access to good jobs, high levels of public safety, and public amenities such as parks and libraries.

Without new homebuilding, IZ can effectively freeze neighborhoods in architectural amber.

IZ balanced with offsets is more than an affordable housing policy. It’s a policy for opening opportunity to those long denied it. It’s a bold approach to integrating neighborhoods by class; over time, it would give chances to a substantial share of people with lower incomes and wealth to live in opportunity-rich areas otherwise affordable only to people with greater means. If the offset for developers takes the form of permission to build extra apartments—extra density—IZ is also a path beyond carbon: compact, walkable, bikable, transit-rich communities may be the most effective antidote to internal-combustion-based transportation yet discovered.

Yet few policies that cities have legal authority to adopt on their own hold so much potential for doing good if they’re done right but also for doing so much ill if they’re done wrong. If IZ imposes costs that it doesn’t sufficiently offset, it will suppress homebuilding. Without new homebuilding, IZ can effectively freeze neighborhoods in architectural amber, choke off housing choices, inflate home prices, accelerate the displacement of working families, erect walls to opportunity and inclusion, and forestall both density and affordability. Done wrong, IZ is a curse.

The two main obstacles to getting IZ done right

Though the argument for IZ with benefits to balance costs that we’ve just summarized is not controversial among most housing analysts and economists, it is deeply at odds with popular perceptions. Many people active in local politics—including many neighborhood groups, social justice advocates, politicians, and ordinary voters—seem convinced that developers make so much money they can easily absorb the costs of subsidizing rent for a share of their tenants. Go to any community meeting on housing in a prosperous city in Cascadia or beyond, and you’re likely to hear statements along the lines of: “Developers make huge profits and need to pay their fair share.” “If landlords weren’t gouging tenants, we wouldn’t have to force them.” “We need affordable housing, and they’re just going to have to pony up.”

No, real estate developers don’t win many popularity contests, and sticking it to them holds great appeal for many. The truth is, though, imposing IZ not balanced with offsets sticks it to the community, not developers. IZ without offsets will cause developers to build fewer homes—but only temporarily. When the paucity of construction yields a worsening shortage of housing, the heightened competition for homes pushes rents up that much faster. Once housing prices rise enough to make up for the expense of the new IZ rules, developers resume construction. But now every home-seeker in town has to pay more for her home, not just during the slowdown in building but ever after.

Other IZ advocates make a more nuanced argument. They do not criticize developers or landlords, do not assume outsized profits, and do not aim to punish them for their purported greed. Rather, they argue that homebuilders can cover the full costs of IZ by paying less for development sites. This argument has just enough truth in it to require examination. But in the end, it—just like the developers-are-rich-so-make-them-do-it argument—collapses under scrutiny. In this article, we take these arguments apart, piece by piece, but first, we fill in some details about how IZ works.

IZ: How and where it works across North America

IZ leverages private dollars, rather than scarce public ones

Inclusionary zoning is an increasingly popular response to the housing affordability squeeze in prospering North American cities. As sources of funding for housing subsidies in the United States have been drying up, IZ has gained favor because it provides subsidized housing without tapping strapped municipal budgets.

Nearly 500 municipalities across the continent have adopted IZ rules of one kind or another; California and New Jersey account for almost two-thirds of the programs. In Washington State, the Seattle-area cities of Redmond, Kirkland, and Kenmore have adopted IZ, and Seattle is currently developing a new IZ policy. Last spring, Oregon repealed a 17-year-old ban on IZ, and in response, Portland has already proposed an IZ program. About a third of the cities in the Metro Vancouver, BC, region have IZ in place, including Vancouver proper since 1988. This month Los Angeles became the latest major US city to join the IZ club.

IZ takes many forms

The requirements of IZ programs vary. In Boston, for example, 13 percent of the units in new buildings must be offered at rent affordable to a household earning 70 percent of the area median income ($62,000 for a household of three). New York City requires 20 percent affordable units for 80 percent of area median income ($78,000 for a household of three). Some cities allow developers to pay a comparable fee in lieu of providing subsidized units in their buildings; that money funds affordable housing projects elsewhere.

To compensate for the cost of the affordability mandates—whether that’s subsidized units or an in-lieu fee—good IZ policies are balanced with “offsets” for homebuilders. Typical offsets include expedited permitting, fee waivers, tax abatements, modified development standards, density bonuses (typically height increases), and reduced parking requirements. Seattle’s proposed Mandatory Housing Affordability program, for example, is coupled to modest upzones that give builders the opportunity to create more valuable buildings to help them manage the cost of including subsidized homes. New York City allows a 33 percent increase in building size. In contrast, San Francisco offers nothing at all to offset the financial encumbrance of its IZ requirements.

IZ’s impacts are difficult to assess

A handful of empirical studies have attempted to assess the real-world performance of IZ programs, and not surprisingly, the results are inconclusive (here is a literature review)—not surprising because isolating the effects of IZ is a triply daunting prospect. First, IZ programs are mostly municipal (city-based), while their effects spill outward into whole housing markets, which are metropolitan (regional) in scale. Second, IZ programs tend to be modest, and their effects are difficult to discern from the background noise of other policies and changing economic conditions. Third, some IZ programs are well-designed with balanced offsets, and some are not. If the value of the offsets negates the expense of the subsidized housing, a finding of no measurable effects on the housing market is just what you would expect (for examples, see this previous discussion). Indeed, a common thread in the literature is that offsets matter:

Programs with no offsets can lead to lower overall numbers of units produced…. Programs in strong housing markets that have predictable rules, well-designed cost offsets, and flexible compliance alternatives tend to be the most effective.

IZ’s potential performance can also be gauged at the project scale using standard real estate economics. For example, the New York City Housing Development Corporation recently commissioned a study of that city’s IZ policy. The report corroborates the importance of offsets, concluding that “[IZ] requirements work best… where returns are aided by the revenue from additional units allowed by changes in zoning.” Furthermore, feasibility “requires the availability of a 421-a benefit,” a valuable city property tax exemption that also functions as an IZ offset. (For those interested in running the numbers on IZ and offsets, try one of these online calculators.)

[list_signup_button button_text=”Like what you|apos;re reading? Get the latest Sightline housing research right to your inbox.” form_title=”Housing Shortage Solutions” selected_lists='{“Housing Shortage Solutions”:”Housing Shortage Solutions”}’ align=”center”]

Why developers can’t eat the costs of IZ

The rules of risk versus return

Like any financial investment, private housing development is ruled by one equation: risk versus return. Developers, like them or not, build homes when they expect their income from rents or sales to cover all the costs of building (from land acquisition to lawyers, architects, engineers, construction materials, contractors, marketing, and interest on their loans) and still provide them a surplus that justifies the risk.

And the risk is considerable. A few things going wrong—a major construction defect, a slump in the market, a lawsuit, a delay in permitting—can easily lead to losses or even bankruptcy. Regulations that impose costs on developers worsen the risk-reward ratio and ultimately result in fewer new homes built.

Regulations that impose costs on developers worsen the risk-reward ratio and ultimately result in fewer new homes built.

In specific instances, a developer may be willing to take on a project even after its potential profit has been pared down by un-offset IZ. But overall housing production does not behave in such a binary fashion, as if there’s a certain profit threshold at which development turns off and on like a light switch. No, the sum of real estate development decisions across a city is probabilistic. The rate of new housing constructed is proportional to the potential payoff. Reduce the incentive to build by imposing new requirements for reduced-price units, and you get less housing.

In cities such as Seattle and Portland, where a housing shortage and white-hot local economies are driving up prices fast, construction is currently booming. Still, the number of new homes is trailing the ballooning pool of home seekers. Any slowdown in construction will raise prices even faster. Housing development rendered infeasible by added regulatory costs becomes feasible again if and when climbing prices boost the proposed building’s future income high enough to make up for those added costs. Developers wait it out. The real losers in this dynamic are the people with low incomes who are priced out of the city because homebuilding was delayed.

No free lunch with investors

Can developers wriggle out of the cardinal rules of real-estate economics, so that any net expenses imposed by IZ do no harm to housing affordability? Can they just eat the cost, with no ill effects? The short answer is, almost always, no. Here’s the long answer.

In most cases, investors, not developers, establish the required return on investment for housing construction. Banks will not lend to fund construction if the potential returns are low. Investors always have the option of directing their capital to investments with better return/risk profiles. They might, for example, divert their funds to an apartment project in a neighboring municipality or move it from real-estate loans to business loans or some entirely different type of investment. The same goes for the few developers with pockets deep enough to finance their own projects: if more lucrative options present themselves, why build homes?

Two ways to meet investors’ demands

To satisfy investors and lenders, developers must find a way to maintain sufficient return on investment when faced with added costs, and there are only two ways they can do that: (1) increase the income derived from the building or (2) reduce the cost of developing it.

The first option—setting higher rents or sales prices—typically isn’t an option at all. Competition among renters or buyers (a.k.a., “the market”) establishes how much they will pay, and developers are already assuming that their projects will deliver the maximum market price. No investor would take seriously a developer proposing a project that can only pay for itself by charging above-market rents. In a slim minority of cases, it may be possible for developers to make up for added costs by modifying their apartment designs to command higher rents. If so, IZ will undermine its own intent by driving up average market rents—the city gets more “luxury” homes and fewer homes affordable to the average working family. But such cases are rare, because developers already search for the most profitable building design.

That leaves the second option, namely, cutting the cost of development. Can developers make cheaper buildings? Not by much. They have no choice but to pay market rates for labor and materials. Sure, some developers manage to squeeze more out of a dollar than others, but competition among them already creates immense pressure to maximize efficiency and cut expenses. The adoption of IZ doesn’t suddenly open a door to closets full of new cost-saving techniques.

Of course another way developers can cut costs is to accept smaller paychecks, and in the end, that’s what they all do when hit with unforeseen expenses—it’s a high-risk business. But before a development project begins, all the foreseen expenses go into a developer’s spreadsheets, and they all come down to the bottom line. Expenses imposed by IZ without balancing offsets can only cut so far into the paycheck before developers will take a pass altogether and build no new homes at all. This effect is, again, not like a light switch: on average, the smaller the potential paycheck, the less likely it is that a developer will pursue construction. Some developers will still build, but not as many, and across a whole metropolitan housing market, prices will rise.

Landowners don’t have to eat IZ’s costs either

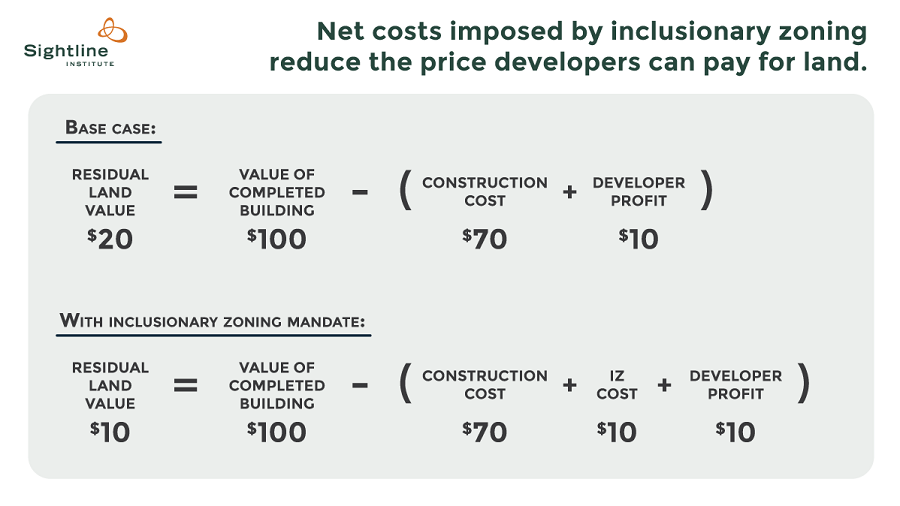

The one remaining major outlay is for land, and developers can decide how much they are willing to offer for that. The maximum price a developer will bid for land—known as residual land value—is set by how much is left in a project’s total budget after all the other development expenses are covered. If IZ drags down the balance sheet, a developer will have less to spend on the land, and the residual land value—the maximum land price that still allows a profitable development—drops accordingly (see diagram below).

But there’s a catch: sellers do not have to accept lower prices.

Consider a hypothetical small commercial property owned by someone who hopes to sell out and retire but needs to accumulate a big enough nest egg before he can do so. The sooner he gets the requisite offer, the sooner he can sell. If the city enacts a new IZ program that cuts what developer can pay for land by, say, 20%—a price hit likely in the range of half a million dollars for a small apartment development site—that owner will likely hold off on selling. He will bide his time and continue collecting the commercial rent until housing prices rise enough to counteract the bite IZ took out of his property value.

This “willingness-to-sell” factor was the basis for the San Francisco Controller’s Office study of “Prop C,” a ballot initiative passed in June 2016 that raised the city’s IZ requirement. The controller assumed that if Prop C reduced the amount developers could pay for building sites enough below the norm, property owners would decline to sell. The report concluded that Prop C’s 25 percent maximum mandate—requiring a quarter of new units be reserved for households with incomes from 55 to 100 percent of the area median—was too heavy a burden: the drop in the prices bid for land would stymie sales and therefore impede the construction of new homes.

Analogous to the suppression of construction caused by added costs, however, it is misguided to assume, as the San Francisco analysis does, that willingness-to-sell turns on and off like a light switch among all land owners. On average across a city, the rate of property sales to housing developers will decline along with the dollar amount developers offer. Scaling back IZ’s affordability mandates to lessen the hit on land values—as recommended by the San Francisco Controller’s study—will relieve the suppression of housing production to some degree, but it won’t shrink that negative impact to zero.

Or do they? IZ and land economics

Peculiarities about the economics of land, some IZ advocates contend, contradict what we’ve just argued. Here’s how their reasoning goes.

Within any city, the supply of land is fixed. (“Buy land,” joked Mark Twain, “they’re not making it anymore.”) This fixed supply yields an unusual relationship between price and supply. For conventional commodities—donuts, let’s say—the higher the price people will pay, the more donuts produced, and vice versa. Supply varies with price. In contrast, economists call land an “inelastic” resource: the price buyers are willing to pay has no effect on the supply. As such, any regulation or fee that knocks down the value of raw land does not reduce the availability of land for purchase.

Because supply is inelastic, the argument continues, when developers bid less for land, landowners have no choice but to sell at the reduced price. Landowners are forced to eat those losses, and sales for housing construction proceed unimpeded. For example, the Seattle-based Urbanist blog made this argument (here, here and here) in support of an all-fee form of un-offset IZ called a “linkage fee.” But this reasoning is critically flawed: it erroneously assumes that a targeted fee on development works like a “land value tax” (see Appendix A-2 for background).

A land value tax is a like a property tax with one key difference: it’s assessed only on the land itself and not on the improvements, that is, not on the value of the buildings standing on the land. Because bare land is inelastic, a pure land value tax does not reduce the availability of land that can be purchased for housing development or any other use—and that’s a big part of its appeal. Under a land value tax, all landowners pay a uniform rate, and they cannot avoid it. IZ, in contrast, takes effect only when new housing is built. The property owner can avoid IZ’s mandates entirely (or its in-lieu fees) simply by not building anything at all. IZ without offsets is, in short, a disincentive to build.

Furthermore, in urbanized areas, most new housing is built on property that had been generating revenue for the previous landowner—another reason expenses imposed by IZ do not behave like a benign land value tax. If the existing revenue stream is large relative to the land value, a reduction in land value caused by IZ is more likely to tip the scales against selling the property. In other words, unlike a land value tax, IZ without balancing offsets most certainly can strangle land supply (see Appendix A-3 for more details).

Un-offset IZ especially hinders property sales for housing development in places where prices and rents only marginally justify construction of new apartments and homes in the first place. Ironically, these areas are often the ones that already suffer from lack of investment. In Seattle, for example, neighborhoods in the Rainier Valley located near light rail stations fall into this category.

In high-demand US cities, lowering land values leads to fewer new homes in the near-term and escalated rents and home prices thereafter.

Conversely, in many locations in any growing city, the rent revenue from housing that could be developed dwarfs the existing use’s revenue stream, in which case un-offset IZ—as long as it’s not exceptionally onerous—will carry relatively little weight in the decision to pursue development. Other places fall somewhere in between. But the inescapable truth is that un-offset IZ will decrease the likelihood that new homes get built. And each project rendered infeasible might be 200 homes not available, which through the machinations of the housing market shuts about 200 low-income households out of the city.

Lastly, while bare land may be inelastic, the construction of housing is definitely not. Higher prices spark greater production, as can be observed in any city experiencing a housing boom. For example, a study of Manhattan found that “permitting activity was strongly positively correlated with lagged [housing] price changes…, a pattern we would expect in a well-functioning, unregulated market.” In other words, when prices dropped, so did homebuilding. And if prices affect the rate of housing development, then by default, prices must also be affecting the rate of property sales for development—that is, the sales are elastic.

To sum up, the key point here is that the depression of land values isn’t a get-out-of-jail-free card for IZ. Because in high-demand US cities, lowering land values leads to fewer new homes in the near-term and escalated rents and home prices thereafter.

IZ: Avoiding the backfire and realizing the potential

In cities where the lack of new homes is sending prices soaring, policymakers must carefully assess regulations that may hold back housing construction. Inclusionary zoning is no exception, notwithstanding its intent to create subsidized affordable housing. The allure of IZ is understandable: it “makes the developers pay.” It adds no expense to public budgets. It integrates affordable units into great neighborhoods.

But the promise of IZ is matched by its perils. If IZ imposes costs on homebuilding, on net, fewer homes will be built. There is no free lunch. There is no wiggling out of the economics. IZ without balancing offsets will push some prospective housing developments from black to red ink, suppressing housing choices and driving up housing prices for everyone. Rising prices, in turn, drive displacement of cities’ families and individuals with low incomes and wealth. In this way, un-offset IZ can effectively function precisely as what its proponents aim to overcome: exclusionary zoning. In places with housing shortages and rising prices, un-offset IZ is a zero-sum game at best: it helps affordability by creating some subsidized homes, but hurts affordability overall by hampering the creation of more homes overall.

Fortunately, balancing the costs of inclusionary zoning—especially with upzones, as Seattle proposes to do—can realize IZ’s promise: more market-rate housing, more affordable housing, more integration of neighborhoods by class, more choice for families and individuals, slower housing price increases for everyone, more density, more walkability, less climate change.

That’s a future worth imagining—and fighting for.

Appendix

The following notes provide additional details that support the main thesis of this article. We relegated them to this appendix because we suspect only the IZ aficionados will want this level of detail.

A-1: Something even better than IZ with offsets?

Our argument for the importance of offsetting IZ’s costs—ideally with upzones—begs a question: Even if properly offset, doesn’t IZ result in fewer feasible housing projects compared to the case of those same offsets applied alone? Wouldn’t offsets without IZ be even better than IZ with offsets? For maximizing overall housing choices, the answer is: yes!

Accordingly, in a perfect world, cities could do best by enacting naked upzones and integrating subsidized housing throughout their neighborhoods using tools other than IZ. Upzoning to maximize private development minimizes the need for subsidized housing in the first place, because it helps control everyone’s housing prices. The best way to fund subsidized homes is a land value tax (more on why, below), but a regular property tax would be a good second choice. Other potential sources include property tax abatements in exchange for below-market-rate units, municipal bonds, dedication of publicly owned land, real estate excise tax, and hotel tax (ideally including Airbnb).

A drawback of IZ is that its burden falls only on those who build housing. Property owners of existing buildings reap the benefits of appreciation in fast-growing cities: they sell at higher prices or collect higher rents. Yet under an IZ program, these owners, whose property values have increased largely due to the efforts of the surrounding community as a whole, nevertheless contribute zero toward the public good of providing affordable housing. IZ lets the majority of landowners off the hook. In contrast, land value taxes, standard property taxes, and bonds are shouldered equitably by all property owners.

All that said, in the real world, where public perceptions define what is politically possible, IZ with offsets is a good compromise, especially if it yields upzones that wouldn’t have been politically acceptable otherwise. Upzones allow more housing on less land, and that’s what matters most for creating an inclusionary, sustainable city. On the other hand, imposing IZ as a means to capture land value increases caused by past upzones is counterproductive: it is effectively a downzone—it results in less housing built compared to doing nothing.

A-2: Land value taxes

We love land value taxes, a rarely used variant of property taxes that are powerful tonics for prosperity, social equity, and compact development. And that’s why it’s so important to understand why IZ is a different animal.

The idea of a land value tax was first popularized in the late 19th century by writer Henry George, who advocated “taking for public use those values that attach to land by reason of the growth and progress of society.” This rationale still resonates today as property values surge in high-demand cities such as Seattle. Why should a landowner reap unearned gains largely derived from the work of all the people who invested in the surrounding community?

Unlike IZ, land value taxes encourage landowners to maximize income from all parcels by making full use of them. It discourages land speculation, a parasitic investment strategy that involves buying and holding underused urban land, such as surface parking lots and depreciated old buildings in prime locations, then waiting for land values to surge. By taxing land values, not building values, land value taxes encourage dense development.

An IZ program, absent sufficient offsets, acts like a targeted tax that penalizes conversion of existing uses to housing. In contrast, a land value tax penalizes landowners for not developing their properties to the highest and best use—the owner pays the same tax whether it’s a trash-strewn vacant lot or a $200 million glass tower. In fast-growing cities, the highest and best use is usually high-density multifamily housing, which is precisely what’s most needed to correct for a housing shortage.

A-3: Existing uses and land elasticity

In the largely built-out, fast growing cities where IZ is most commonly found, most new housing is developed on property that had been generating income for the previous owner. Almost all land in any expensive city produces revenue—even if there’s no building on the site, it can be used for paid parking.

The important role of existing uses in the dynamics of housing construction is reflected in countless zoned capacity estimates in which municipal planners assess development probability according to the improvement-to-land-value ratio: the lower the ratio, the more likely a parcel of land will be developed. Improvements that generate robust revenue have higher value, reducing the likelihood that the property will be sold for development. Likewise if a costly regulation forces land value down, the probability of development also drops.

The income stream from existing uses can vary drastically compared to the value of the land alone. If it’s a surface parking lot in a zone that allows skyscrapers, for example, the value of the revenue from parking is a tiny fraction of the value of the land, since it has the potential to hold a very expensive building. In this scenario, added regulatory costs would likely have little impact on willingness to sell because the price offered, though reduced, would still be much higher than the value of the income stream from parking.

In contrast, if it’s a functioning retail strip mall in a zone that only allows four-story apartment buildings, the value that could be created by developing may not be much more than the value of the existing commercial rent revenue. In this scenario, added regulatory costs could be enough to push down the price developers can offer for the property to the point where keeping the income-generating strip mall becomes more financially attractive than selling it. In other words, land is clearly not inelastic in this situation: a financial encumbrance on development reduces the availability of land for the construction of new housing.

A-4: When the landowner is the developer

In some cases, a would-be-developer already owns a site when a regulation is enacted that jacks up development expenses. In this scenario, the landowner is flat out of luck because she cannot make up for lost returns by paying less for land that she already owns, and there are no other options to recoup the loss. Any extra costs imposed by IZ will decrease the likelihood of housing construction, end of story.

Furthermore, if a feasibility assessment gives the thumbs-down to development for the owner/would-be-developer, then the same assessment will also give the thumbs-down to an offer for the property at the residual land value. After all, the buyer and seller both do the same math to estimate how much money could be made by redeveloping the site. Added regulatory costs put the brakes on homebuilding regardless of whether a property sale is involved.

A-5: Some inconvenient contradictions

The contention that the inelasticity of land renders regulatory fees on housing construction benign leads to contradictions that further illustrate the flaws in the argument.

First, consider the hypothetical case in which a fee is high enough to reduce the residual land value to zero—that is, the fee has pushed the cost of building so high that there’s no budget left to pay anything for land. Certainly no landowner will accept an offer of zero dollars. How can one reconcile the fact that a large fee would reduce the land supply for development to zero with the contention that a smaller fee has no impact at all on land supply?

Second, if one asserts that added costs on development don’t curtail production, it follows that reduced costs won’t boost production. A developer incentive that cuts the cost of construction would only result in builders bidding more for development sites. And so according to those who believe that the economics are controlled by land inelasticity, higher prices would not increase the rate of property sales for development, yielding no gain in housing production. And worse yet, all the financial benefit of the publicly funded incentive would be pocketed by private landowners who garner higher land prices.

Where that reasoning leads is that any time a city proposes expedited permitting or a property tax exemption or any other means of incentivizing housing development, it is unknowingly giving away cash to lucky landowners. In fact, it means it’s impossible for governments to use financial tools to influence private development in any way whatsoever because any such intervention is just absorbed into land prices! That would likely come as a surprise to the thousands of municipalities that have such policies on the books.

A-6: Are the negative impacts only temporary?

Many IZ advocates who concede that added development costs can choke the availability of development sites and impede housing production argue that the effects are temporary. In short, the claim is that “over time, developers should be able to negotiate lower prices from landowners.” It’s a curious assertion. None of the arguments presented in this article become any less valid with the passing of time. What could enable such a shift in economic decision making? Some amount of subjective irrational judgement likely plays a role in evolving expectations, but that’s shaky ground on which to base the expected outcome of a far-reaching affordable housing policy. If eventually “the requirements may be absorbed as a cost of doing business in the jurisdiction,” that is only another way of saying that housing production will proceed when rents rise high enough to overcome IZ’s costs—and that’s no win for affordability, inclusion, or the struggle against displacement.

Thanks to Rick Jacobus and Kristin Ryan for reviewing this article, and to Margaret Morales for help with research.

Comments are closed.