For the fifth time in US history, and for the second time in the past five presidential elections, the candidate who won the most votes lost the presidential election. The fault lies with the archaic Electoral College, an 18th-century compromise that still controls the elections of the 21st century’s most powerful country.

But the notoriously hard-to-amend US Constitution has the solution baked in: the states control the Electoral College, so the states have the completely legal, practical, and actionable power to change the Electoral College so that it elects the popular winner. And some of them are actually making moves to do just that.

How the winner-take-all Electoral College strategy fails the voters and states

The winner-take-all Electoral vote overrides the popular vote

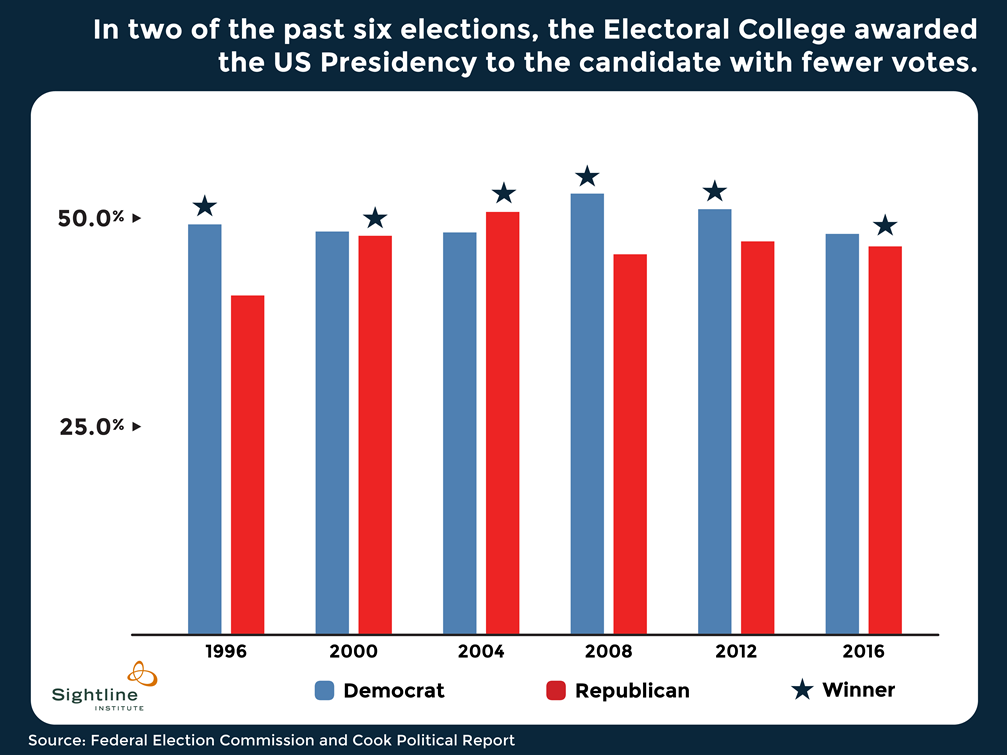

The chart below shows the percentage of the vote that the Democratic and Republican candidates for president won in the past six elections. When the election is clear-cut—greater than a few percentage points’ difference between the top two candidates—the Electoral College agrees with the people.

But when the election is close—within two percentage points—the Electoral College sometimes picks a president that a majority of voters didn’t want. Not only can a candidate become President of the United States without support from a majority of voters (more than 50 percent), he doesn’t even need to win a plurality (more votes than any other candidate). And that makes Americans wonder what “one person, one vote” really means.

The winner-take-all Electoral vote skews campaigns and policies to favor swing states

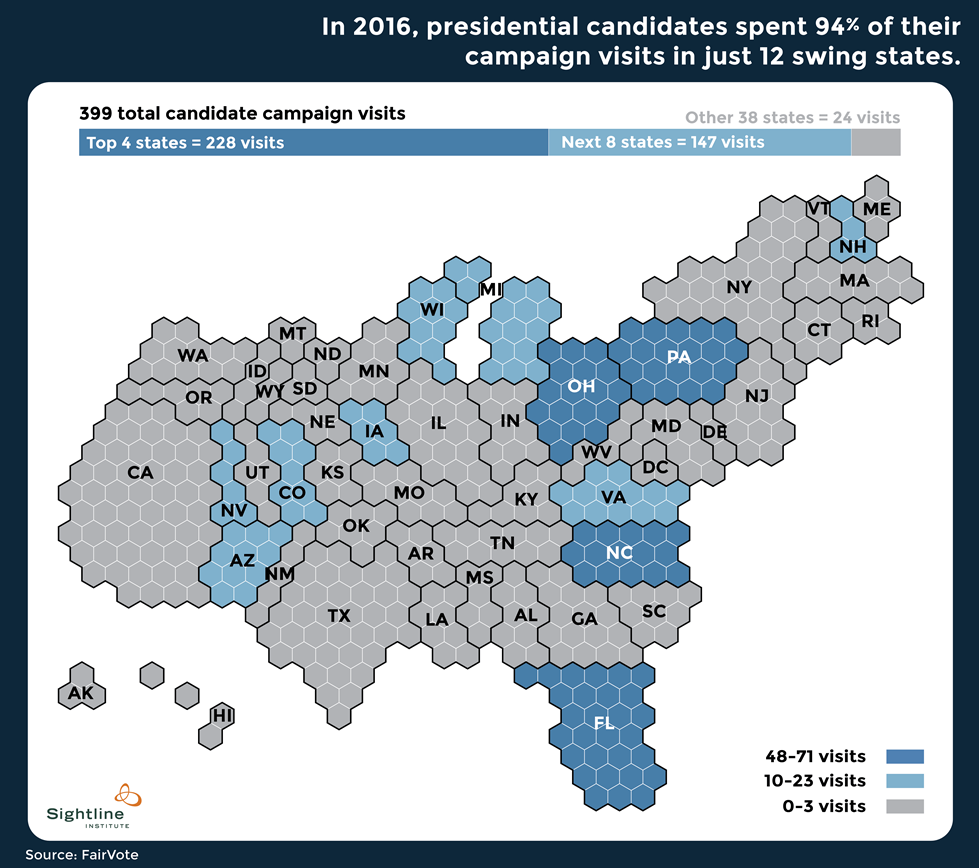

President-elect Trump correctly pointed out in his tweets that he would have campaigned differently if he were trying to win the popular vote. Under the current Electoral College system, candidates spend 91 percent of their campaign stops in just 11 states and two-thirds of their campaign stops in just six states. The map below shows the states sized according to their electoral college votes. Candidates did at least 48 events in each of the four dark blue swing states, but flew over most other states.

And swing states don’t just get candidate visits; they get more money and special treatment after the election is over, too. Swing states receive seven percent more presidentially controlled grants, twice as many disaster declarations, more Superfund and education requirement exemptions than “safe” (non-swing) states do, and their priorities more influentially shape federal policies on economics and trade.

Year after election year, Oregon—and other “safe” states like it—get exactly zero presidential campaign visits. Oregon votes just don’t make a difference to candidates: as long as the Democratic candidate wins more votes than the Republican, she will get seven Electoral votes whether she wins one million or two million Oregon votes, and the Republican candidate will get zero electoral votes whether he wins a half-million or one million Oregon votes.

Because one million Oregon votes potentially hanging in the balance are basically worthless, candidates continue to ignore the Beaver State. New Hampshire, with just one-third as many residents as Oregon, received 21 visits this presidential campaign season, and thus likely more grants and influence after the election, too. Iowa and Nevada, also with well fewer residents than Oregon, received 21 and 17 visits respectively.

So what to do instead? A national popular vote via the Electoral College

Enter the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, by which state legislatures would pledge to assign Electoral College votes to the popular winner once enough other states have also signed on to guarantee the popular winner. The Compact would not abolish the Electoral College, but instead use it to execute the will of the people.

Who controls Electors? The Constitution says: The states

The original United States Constitution gave state legislatures great power in the federal government: state legislatures chose their respective US Senators, as well as their Electors to choose the US President. In 1913, the 17th Amendment changed Article I, Section 3, to instead elect US Senators by a popular vote of the people. But state legislatures still control presidential elections through the Electors: Article II, Section 1, Clause 2, of the US Constitution mandates, “Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors.” The Supreme Court affirmed that state legislatures have exclusive control of the Electors.

If enough states chose to cast their Electoral votes for the popular winner, US voters would no longer see a mismatch between who wins the popular vote and who wins the presidency.

Initially, in many states, people voted for Electors who pledged to vote for a particular candidate, and the state cast its Electoral Votes between tickets according to how many votes each Elector won. Eventually, states realized they could have more say by shifting to a winner-take-all Electoral College strategy, instructing their Electors to cast all their Electoral votes for one ticket instead of splitting them between tickets. Today, in all states, people vote for the presidential candidates, and most state legislatures require Electors to cast their Electoral College votes for the candidate who wins the state’s popular vote.

But the Constitution leaves the decision of how to select Electors and how to distribute their votes completely up to state legislatures. State legislatures could instead, for example, require Electors to cast their Electoral College votes for the candidate who wins the national popular vote. And if enough states chose to cast their Electoral votes for the popular winner, US voters would no longer see a mismatch between who wins the popular vote and who wins the presidency. The Electoral College would always agree with the people.

States support a national popular vote—when they can do it together

When it comes to casting Electoral votes for the national popular winner, states don’t want to do it alone. Acting alone, a “blue” state like Oregon would have simply made President George W. Bush’s 2004 Electoral College win even bigger and would not have changed the 2000 outcome. States will only want to switch if enough other states do the same to ensure they are collectively electing the popular winner.

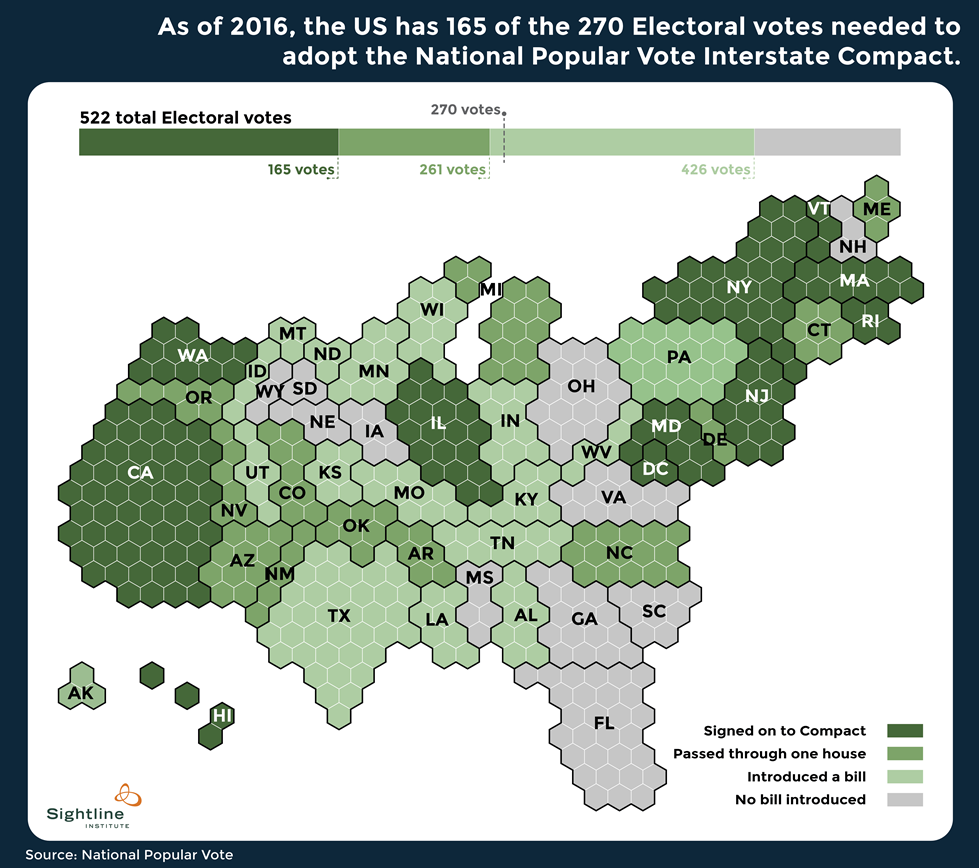

The Interstate Compact takes effect once states controlling at least 270 Electoral Votes have signed on, ensuring that the most popular candidate will also win the Electoral College. So far, 11 states representing 165 electoral votes have signed on. Among them are California and Washington. Oregon would bring the total to 172.

Oregon, Colorado, Nevada, and eight other states have passed the National Popular Vote bill through one legislative chamber in recent years but failed to do so in the other (more proof that Nebraska’s unicameral legislature is a better idea than “having the same thing done twice, …by two bodies of men elected in the same way and having the same jurisdiction”). If each of those eleven states managed to get the bill past the finish line, the compact would have 261 electoral votes—just 9 away from implementation. Fifteen other states have introduced a bill, sometimes passed it through committee, but not passed it out of a house.

The map below shows the states sized according to their electoral college votes. Dark green states have signed on to the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact; light green states have passed it through at least one house; and the lightest green have introduced a bill in the legislature.

Only so-called “blue” states have signed so far, but many of the states that have passed it through one chamber are solidly red. For example, “safe,” “red” Oklahoma passed a bill through the state Senate in 2014; Arkansas passed bills through the House in both 2007 and 2009; and in 2016, the Arizona House of Representatives, a Republican-controlled body in a fairly “red” state, passed a National Popular Vote bill with a whopping two-thirds support: 40-16!

Voters support a national popular vote, too

By wide margins, Americans think the candidate with the most votes should win the presidency. Even President-elect Trump said in a 60 Minutes interview on November 13, 2016:

I would rather see it where you went with simple votes. You know, you get 100 million votes and somebody else gets 90 million votes and you win. There’s a reason for doing this because it brings all the states into play.

By wide margins, Americans think the candidate with the most votes should win the presidency.

Yes, the person with the most votes should win. Not only does that seem fair and make it seem to people like the system isn’t “rigged”; it also makes every voter in every state important, because every state is a swing state, and every vote counts. (Trump changed his tune on November 15, tweeting that the “Electoral College is actually genius.”)

Oregonians on both sides of the aisle support a national popular vote. In a 2008 poll, 76 percent of Oregonians, including 82 percent of Democrats and 70 percent of Republicans, supported a national popular vote for president. The Oregon House of Representatives has listened to the people and supported a National Popular Vote bill year after year:

- In 2009, the Oregon House of Representatives passed the National Popular Vote bill by 39-19.

- In 2011, 23 representatives sponsored a National Popular Vote bill.

- In 2013, the Oregon House of Representatives passed the National Popular Vote bill by 38-21.

- In 2015, the Oregon House of Representatives passed the National Popular Vote bill by 37-21.

- In 2015, a majority of Oregon Senators also sponsored a National Popular Vote bill, but it still didn’t get a vote on the Senate floor.

In 2017, Oregonians could pressure Senate President Peter Courtney to put the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact bill to a vote.

And candidates could support even an unofficial compact

Even if the Compact didn’t get to 270 by 2020 but made impressive progress, the top two candidates could choose to honor the expressed will of the people. They could both agree, publicly, that the candidate with the most votes would win. Then, both candidates would campaign for people’s votes, not for Electoral votes, and they would ask pledged Electors to honor their public agreement.

A popular vote would be good for “safe” states like Oregon, no matter who wins

Better representation for all of a state’s voters

With a national popular vote, every single vote would count. Every vote could put a candidate over the top in the race to win the most votes nationwide, so candidates would come to previously written-off “safe” states like Oregon and fight to win over every one of its nearly three million eligible voters.

For example, three-quarters of a million Oregonians voted for Trump this year, yet their votes meant nothing under the current winner-take-all Electoral College system. One hundred percent of Oregon’s Electoral College votes went to Clinton. With a national popular vote, conservative Oregonians could mail in their ballots for the conservative candidate and know that their votes contributed to his win.

Greater rewards for states that honor and encourage voting rights

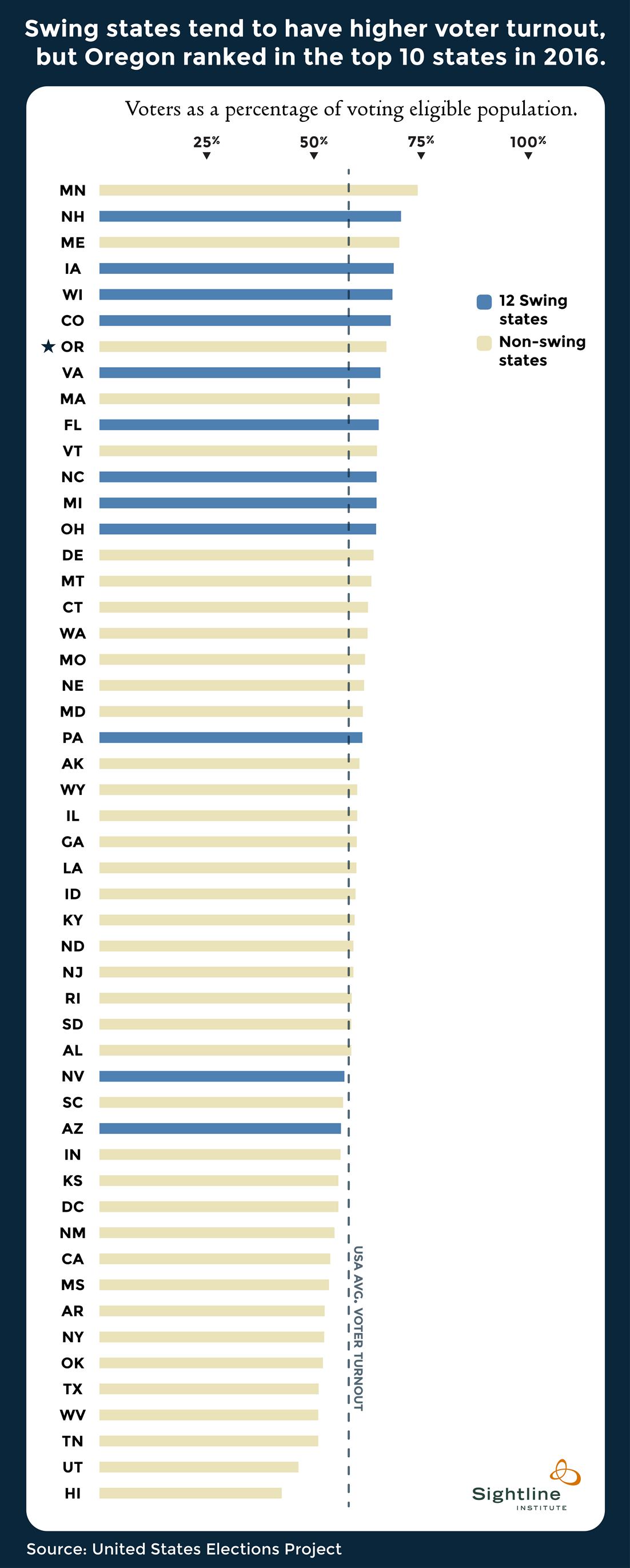

Because the winner-take-all Electoral College strategy makes every vote matter in swing states, swing states tend to have higher voter turnout than average. (The graph below shows states arranged by percentage of eligible voters who actually voted in 2016, with the 12 swing states colored blue.) The Electoral College as it currently operates doesn’t reward Oregon for its enviably high voter turnout, consistently among the top 10 even though it is not a swing state. Oregon will get seven Electoral College votes whether all three million Oregon citizens mail in their ballots or only one-third of them do.

But if America’s Electoral College were held accountable to the vote of the people with something like the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, Oregon’s model efforts over the years to honor Oregonians right to vote, which have already paid off financially, would pay off politically. Oregon’s high voter turnout would have a bigger impact on the national popular vote results because its eligible voters would be turning in more ballots. And with a record 88 percent of eligible voters in Oregon registered to vote thanks to New Motor Voter, Oregon would be positioned to punch well above its weight in presidential elections.

A better Electoral College system means a more balanced democracy

Voters across the United States think the candidate who earns the most votes should win the nation’s highest office. An Electoral College system that answers to the voters of today rather than archaic rules of yesteryear would advance that shared vision.

It would also mean that voters in states traditionally considered “safe” for one party or another, like Oregon, would finally be important to presidential candidates, who would have to court voters in every state to help them win the national popular vote. And all of those safe states and their voters would finally have more of a say in determining the outcome of the presidential election.

By supporting the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, Oregon could do its part in helping American make that ideal a reality. And along the way, thanks to its hard work to honor every Oregonian’s right to vote, Oregon could win more power and influence as a state and for each of its more than three million eligible voters. That’s what a more balanced democracy could look like.

[list_signup_button button_text=”Like what you|apos;re reading? Get the latest Sightline democracy research to your inbox.” form_title=”Reclaiming Our Democracy” selected_lists='{“Reclaiming Our Democracy”:”Reclaiming Our Democracy”}’ align=”center”]

Comments are closed.