Just after midnight on October 13, 2016, the tug Nathan E. Stewart and its 287-foot oil barge ran aground on British Columbia’s central coast, spilling about 27,000 gallons of diesel and 1,300 gallons of oily lubricants. The inadequate response to the spill’s aftermath confirmed the fears many in BC and Washington have about the two oil pipelines proposed in the province, each of which would drastically increase tanker traffic in the Salish Sea and remote coastal waters. The Northern Gateway and Trans Mountain projects would, if built, deliver nearly 1.5 million barrels of heavy crude oil per day to Northwest shores.

Responding to growing concern about the projects, BC Premier Christy Clark in 2012 announced five conditions that any oil pipeline company would need to meet before receiving approval to build. Among those conditions are “world-leading marine oil spill prevention, response, and recovery systems;” “world-leading practices for land oil spill prevention, response, and recovery systems;” and respect for First Nations treaty rights. The October 2016 spill and cleanup efforts, which are still ongoing, show that BC is not ready to meet any of those conditions, despite assurance from provincial officials and pipeline backers Enbridge and Kinder Morgan.

The first hours of the Nathan E. Stewart spill

The Nathan E. Stewart and its barge were returning to Vancouver from Alaska when the tug collided with Edge Reef in Seaforth Channel, a passage up the central coast, less than twenty miles from Bella Bella. Though the barge was empty, the tug itself can hold thousands of gallons of diesel that are used to power the vessel. The reef punctured three fuel tanks on the tug.

Within 12 hours, the leaking tug was two-thirds underwater. The Western Canada Marine Response Corporation, an industry-owned private company responsible for oil spill cleanup, deployed support vessels with an oil containment boom from a base in Prince Rupert, about 200 miles away, a journey of more than 20 hours by water. Response vessels from closer by arrived on the scene by 11 AM, about ten hours after the spill, but their supplies were insufficient to contain the oil.

Devastation for the Heiltsuk First Nation

Diesel fuel quickly spread onto beaches and into the nearby waters, including the traditional fishing waters of the Heiltsuk First Nation. The nation’s clam fishery, a significant part of its winter economy, was due to open three weeks from the date of the spill. Heiltsuk Chief Councillor Marilyn Slett told newspapers that the spill area is “one of our primary breadbaskets,” hosting twenty-five species that the band harvests. Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans has ordered the emergency closure of shellfish harvesting in the area until further notice, depriving the band of a critical source of income and sustenance. A subsistence crab fishery in the area has also been shuttered.

The Heiltsuk First Nation were among the first responders to the diesel spill, as First Nations so often are when oil spills in BC. The volunteers included elders and youth, and all were largely unprotected from the oil’s toxins save for gloves provided by the Canadian Coast Guard. The Heiltsuk had some modest spill response equipment, but even after combining these with resources of the Coast Guard and the tug’s crew, they were unable to contain the fuel as they waited for the spill response team to arrive with more substantial equipment.

“[T]he spill response we have on our coast is totally inadequate, not just for what some people argue should come if pipelines come from Alberta; it’s not adequate for what we have now going up and down out coast.”British Columbia Premier Christy Clark

Ten hours passed before responders put the first oil containment booms in place, but strong currents pulled those apart before the end of the first day. The replacement booms have stayed in place, but they arrived too late to contain the majority of the spilled oil, which spread throughout surrounding waters. Severe weather caused numerous clean-up delays and continued to spread the oil.

“The spill response is totally inadequate”

The collision occurred in an area classified as a “Voluntary Tanker Exclusion Zone,” a designation along the British Columbia coast from which loaded oil tankers are excluded to help avoid potential spills. The tug and barge involved in October’s collision were able to travel within the passage because the fuel barge is smaller than a standard offshore tanker. The tug had also been given a waiver to operate without a local marine pilot.

The events proved that BC does not have the oil spill response and recovery procedures that officials promised to Northwest residents before oil companies increase their transportation volumes on the Salish Sea. Premier Clark said after the spill that she agreed with pipeline critics regarding the inadequacy of coastal spill response. “[T]he spill response we have on our coast is totally inadequate, not just for what some people argue should come if pipelines come from Alberta; it’s not adequate for what we have now going up and down out coast,” Clark said.

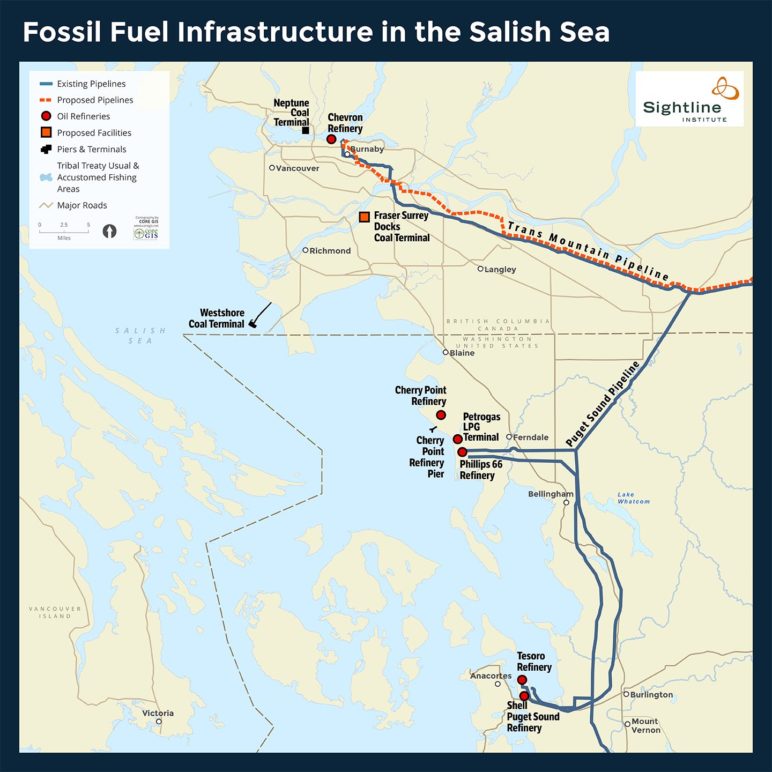

The current response and recovery procedures are certainly not adequate to support the expansion plans for the Trans Mountain pipeline system, which would triple the pipeline’s capacity by “twinning,” or installing a parallel pipeline that closely follows the route of the existing line. The Trans Mountain system transports heavy oil sands crude, sometimes called diluted bitumen, from Edmonton, Alberta, to a terminal near Vancouver, BC, and to several refineries in Washington State. The Trans Mountain Pipeline would increase marine traffic in transboundary US and Canadian waters by at least 348 additional tanker trips annually, which would thread their way through a labyrinth of reefs and islands in the treaty-protected fishing waters of numerous Salish Sea tribes.

Bitumen is particularly hard to recover in the event of a spill, an appalling prospect given how little oil is recovered even from spills of conventional crude. According to Transport Canada, only 10 to 15 percent of a marine oil spill is likely to ever be recovered from open water. Many of the recovery efforts are performative acts that reduce the visibility of oil rather than effective ones that actually remove it from the environment, and what the industry bills as “world class” technologies are in reality highly ineffective except for small spills on sheltered waters. That is, even if Clark’s conditions lead to marine spill response resources that meet the current standard of “world class,” they would not be enough to protect the Northwest’s environment or economy in the event of an oil spill in the notoriously strong currents and tides of the San Juan Islands and Strait of Juan de Fuca.

International opposition to Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain proposal

The Trans Mountain expansion proposal faces strong opposition. In January 2016, the BC provincial government announced that it would formally oppose plans to expand the Trans Mountain pipeline because Kinder Morgan had failed to provide adequate plans for oil spill responses. (The province did not rule out the possibility that Kinder Morgan could meet those requirements in the future.) The cities of Vancouver and Burnaby oppose the expansion. Burnaby, where the new pipeline would terminate, has refused to cooperate with the project and banned project workers from city property. The Tsleil-Waututh Nation in North Vancouver has filed two legal challenges against the project in federal court, and US tribes have raised concerns that an oil spill in the Salish Sea could harm their fishing rights and cultural heritage. First Nations representatives and activists have called on Prime Minister Trudeau to halt Canada’s federal-level review of the Trans Mountain expansion, calling the review process “inadequate,” “flawed,” and “incredibly broken.”

Even so, in May 2016, Canada’s National Energy Board recommended that the governor in council approve the Trans Mountain project, finding that “the benefits of the project would outweigh the residual burdens.” The Energy Board’s recommendation included a list of 157 primarily environmental conditions Kinder Morgan would have to meet. Energy Minister Bill Bennett said in mid-July that Kinder Morgan was close to meeting the 157 conditions and that the main outstanding issue is marine spill response.

A history of similar spills

The Nathan E. Stewart spill showcased BC’s woeful lack of marine oil spill preparation, but it’s hardly a unique incident. In fact, it strongly resembles several previous incidents. In 2011, the very same barge and tug went adrift after an engine failure in the Gulf of Alaska. The tug contained 45,000 gallons of diesel, and the barge contained 2.2 million gallons of diesel fuel, over 1,000 gallons of aviation fuel, and 700 gallons of other petroleum products. (That time, the tug and barge were safely brought under tow and no oil was spilled.)

The Gitga’at Nation is still struggling after the sinking of the BC ferry Queen of the North in early 2006, which for ten years has prevented First Nations members from harvesting seaweed and clams in the area. There are also strong similarities to the Nestucca oil spill, which became an international scandal after inclement weather spread black tar crude from Grays Harbor, Washington, along the outer coasts of Washington and British Columbia.

The Canadian government is expected to make a final decision on the Trans Mountain project by December 2016.

Comments are closed.