At a recent town hall-style meeting about money in politics, a speaker asked the audience how many of them thought they themselves could run for political office. Absolutely no one raised their hand. Then the speaker asked, what if a campaign funding system made it possible for you to raise money from regular people, even if you don’t have a rolodex of big check writers? Hands popped up.

People-empowering campaign finance systems are currently in place in 31 jurisdictions around the United States, and if Citizen’s Initiative 1464 passes in November, Washington State will become the thirty-second. In the previous article in this series, we described how the Washington Government Accountability Act’s Democracy Credits work for you if you’re a voter. In this article, we take the candidate’s view.

The quick guide to Credits for candidates

If you want to run for state legislature using I-1464’s Democracy Credit program, here is what you do:

- Qualify. To show you’re a viable candidate—not a GoodSpaceGuy or a Mike the Mover—you collect signatures and small contributions of support from at least 75 Washington voters. (See details in Appendix 1.)

- Register. Once you have these signatures, you fill out a form with the Public Disclosure Commission (PDC) agreeing to limit personal funds you use to finance your campaign to $5,000 and to fund your campaign by collecting Democracy Credits and other limited contributions.

- Talk to voters. Now, the fun part! You spend your time meeting voters. You might do so at house parties, candidate forums, union halls, street festivals, farmers’ markets, or on hundreds of doorsteps. You talk with voters about their concerns and your positions, ask for their votes, and ask for their Credits. You might bring an iPad, too, so people can assign their Credits to you on the spot. You might also seek the support of organizations with big memberships or loyal audiences—they may turn out to be the gatekeepers to their constituents’ Credits. (See two scenarios of Democracy Credit campaign plans in Appendix 2.)

- Cash your Credits. Credits are like electronic gift cards for your campaign. Once a voter signs them over, the PDC disburses your funds. Cha-ching!

Credits, credits everywhere

As state legislative campaigns are currently run, raising money and winning over voters are two separate activities. The former consists of phoning and visiting PACs and rich people to harvest $2,000 checks; the latter involves talking to people, giving speeches, reaching out to the media, knocking on doors, shaking hands, winning influential endorsements, and advertising.

I-1464’s Democracy Credits would shrink the time candidates have to spend courting wealthy influencers for their donations. Credits make it possible for candidates to consolidate raising money and persuading voters into a single endeavor of reaching out to everyday people.

I-1464’s Democracy Credits mean candidates can make everyday people their donor class.

For you as a candidate, the essential feature of Democracy Credits is that they will be everywhere. They will transform every registered voter—and eventually every eligible resident—into a prospective $150 contribution to your campaign treasury. Washington has more than 4 million registered voters. Four million! Another roughly 800,000 adults are eligible to vote but not registered: convince them to register, and they’ll become potential $150 contributors, too. Starting in 2020, permanent residents and other adults who are not eligible to vote but are eligible under state and federal law to give to campaigns will become potential contributors, too.

In short, almost every adult you meet will be a prospective donor. If they like your positions, these donors will be glad to support you with their Credits, which are otherwise worthless to them. To you, however, they’re real campaign cash from new conversations with ordinary constituents.

[list_signup_button button_text=”Like what you|apos;re reading? Get our monthly democracy reform updates straight to your inbox!” selected_lists='{“Reclaiming Our Democracy”:”Reclaiming Our Democracy”}’ align=”center”]

Changing the rules of the game

Democracy Credits, like the rest of Washington Government Accountability Act’s ethics reforms (described here and here), aim to fix one acute problem: the outsized influence of big money in politics. You, candidate, ran for public office because you wanted to serve the people of Washington. But to run, you have to spend all your time raising money by talking to rich people and special interests, and so, not surprisingly, you gradually assimilate their views.

We’re not blaming you—or any candidates or elected officials. You are playing by the rules. It’s just that, unfortunately, the rules in the era of Citizens United make you answer to the elite donor class, and as noted at the start of this article, they limit who even feels they can run for office in the first place.

The solution, then, is to change the rules. The Washington Government Accountability Act opens up a different path to office, a path that does not have to primarily traverse the terrain of the one percent. Instead, on the Democracy Credit path, you can spend more time courting the votes of ordinary people, regardless of whether they have deep pockets. Or, you could be an ordinary person yourself, engaged in your community and now, thanks to Democracy Credits, with a competitive shot at winning office to represent your community.

The Washington Government Accountability Act makes everyday people into a more empowered political class—be they baristas or barbers, nurses or network analysts. And that makes for a more balanced and representative democracy for Washington State.

Appendix 1: Details about Democracy Credits

If you are running for the state legislature—house or senate—you can qualify to use Democracy Credits by raising a certain number of contributions from eligible individuals, then agreeing to stricter contribution limits and a cap on the amount of Democracy Credit funds you can raise.

Qualifying thresholds

To qualify as a candidate for state legislative office, you must gather 75 contributions of at least $10 each from individuals (not PACs, corporations, or other “corporate persons”) (Section 13(5)). The program may expand in 2024 to include other state offices such as Governor and Secretary of State (Section 13(1)), and the PDC will set the qualifying thresholds for those offices. Over time, the PDC will adjust the number of qualifying contributions to ensure that only viable candidates are able to participate and vanity candidates can not access public funds.

Eligible Democracy Credit contributors

To start, you can only receive Democracy Credit contributions from registered voters (Section 10(3)). But by 2020, the PDC will develop regulations to verify adults who are not registered to vote but who are both residents and also eligible under state and federal law to donate to candidate campaigns. Then, they too will be able to give you Democracy Credits (Section 16(4)).

Contribution limits

If you opt into using Democracy Credits, you must agree to limit personal funds you use to finance your campaign to $5,000 (Section 13(4)). You must also limit most contributions from individuals and groups to half the current amount (Section 10(7)). Specifically, at present, individuals, PACs, unions, and corporations may contribute up to $1,000 per election to legislative candidates. The primary is an election and the general is an election, so candidates who make it to the general can receive $2,000 total from each contributor. If you opt into accepting Democracy Credits, though, you won’t be able to accept more than $500 per contributor per election, or $1,000 per contributor for both primary and general, including any Democracy Credit value they gave you (Section 12(2)). For example, if someone gave you all of her Democracy Credits—$150—plus a $350 check in the primary, she would be maxed out for that election but could write you another $500 check for the general election.

At first glance, you might think opting into the Democracy Credit program will cut your fundraising ability in half. But remember the millions of ordinary voters who don’t currently have enough cash to write you a campaign check, but who under I-1464 would suddenly have $150 to give you if you opt into using Democracy Credits. This new everyday donor class tips the scales and makes fundraising through the Democracy Credits program imminently feasible.

Also, you will still be able to raise money from political parties. I-1464 will not change the amount you can receive from state political parties and caucus political committees—they can still contribute $1.00 per registered voter per cycle, or around $60,000-$100,000 per year, depending on the district. It also doesn’t change the limits on contributions from county and legislative district party committees—they can still give you $0.50 per registered voter per cycle, or around $30,000 to $50,000 per year, depending on the district.

Parties will likely continue to play an important role in state legislative elections, and possibly an even bigger role. Under I-1464, individuals and organizations can give an unlimited amount to exempt state Party Committees, and individuals can give unlimited amounts to non-exempt Party Committees and Caucus Political Committees. These committees, in turn, can then pass on sizable amounts to candidates, including those who opted into using Democracy Credits.

Funding limits

If you participate in the Democracy Credit program, you must agree to a ceiling on the amount of Credits you can cash in. If you’re running for state representative, you may not receive more than $150,000 in Credits. If you’re running for state senator, you may not receive more than $250,000 in Credits (Section 13(7)).

These caps are at the high end of campaign contributions in Washington legislative races in 2012 and 2014: average winning house candidates raised $113,230, and average winning senate candidates raise $262,560. If you collect some checks in addition to maxing out on Credits, you will be able to run a highly competitive campaign.

Other limitations

By opting to use Democracy Credits, you also agree to other limitations, including vowing not to solicit, accept, direct, or coordinate any funds other than Credits and qualifying contributions (Section 13(2)(c)); agreeing to spend Democracy Credit contributions only for specified purposes (Section 13(8)); and opening your books to the PDC at any time (Section 13(2)(c)(vi)).

Schedule

You may begin collecting small contributions in July, sixteen months before a general election. If you want to participate in the Democracy Credit program, you will make sure you don’t collect more than $500 per person leading up to the primary. (The primary counts as one election and the general as another, so if you make it to the general, you can collect another $500 in contributions per person.)

Once you collect 75 qualifying contributions of at least $10 each, you can turn in your paperwork to the PDC. Starting on April 1st of an election year, you may start collecting Democracy Credits (Section 10(1)). The PDC will have sent out Democracy Credit information to registered voters 10 days earlier (Section 11(1)). The PDC will set the last date by which you must qualify to participate. You can collect Credits before you qualify, but you cannot redeem them until you do.

Penalties

If you break the rules, you’re in deep trouble. If you try to buy Credits, for example, you could go to prison (Section 15). If your campaign breaks other rules, you might have to give PDC all the money back.

Appendix 2. Sample Campaign Plans

To figure out how a Democracy Credit candidate might campaign, we pulled campaign numbers from all Washington state house and senate races from 2012 and 2014. We parsed the data to see how much money winning candidates raised, from whom they raised it, and how the numbers differed for incumbents and challengers, and between hotly contested and less competitive races. The scenarios below are hypothetical but rooted in this data. (The Campaign Finance Institute recently constructed hypothetical Washington campaigns with Credits, and came up with similar numbers.)

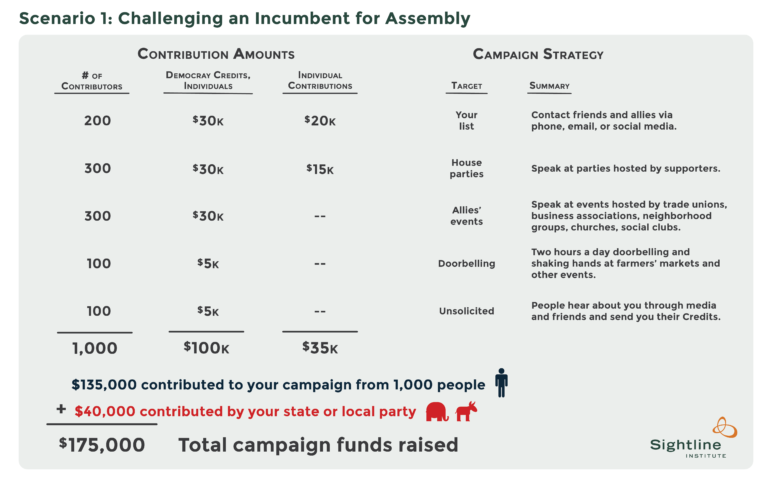

Scenario 1: Challenging an Incumbent for Assembly

The average successful house incumbent raises $105,000 to fund his or her race—about $24,000 from individual people and $81,000 from parties, PACs, unions, and other organizations. An average successful house challenger raises $175,000—about $48,000 from individual people and $115,000 from organizations.

If you’re challenging an incumbent house member, you might aim to raise $175,000: enough for a paid campaign manager, lots of flyers for doorbelling and community forums, and two campaign mailers to likely voters in your district. You can raise a maximum of $150,000 from Democracy Credits (DCs), but you aim to raise about $100,000 from Credits and the remainder from individuals and your political party. Successful challengers in 2012 and 2014 raised an average of $72,349 from political parties, but the scenario below conservatively assumes the Credits lead you to rely more heavily on individuals.

Wow: 1,000 people powered your $175,000 campaign, and you took no money from PACs, corporations, or unions. By contrast, the average successful challenger in a house race in 2012 and 2014 received contributions from just 231 people and raised 65 percent of his or her money from parties, PACs, unions, corporations, and other non-individual donors. The scenario above shows how dramatically I-1464 could shift your campaign strategy, allowing you to spend more time reaching out to a lot of regular people: 1,000 contributors of either Credits or money, and just 23 percent from political parties.

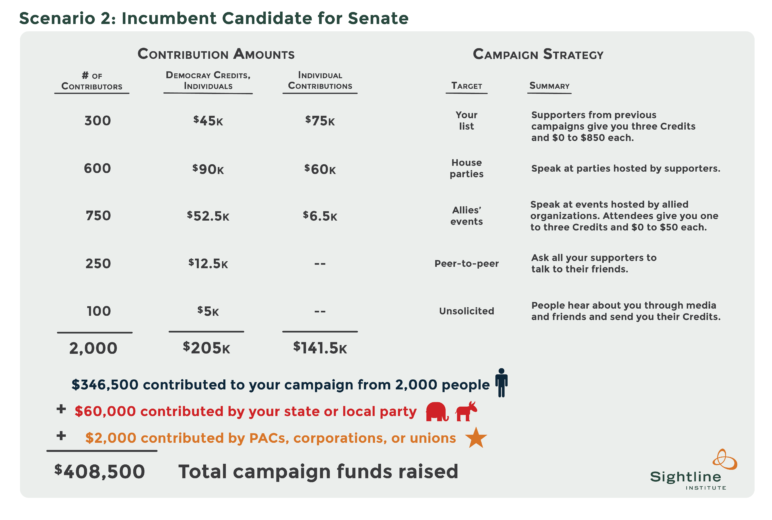

Scenario 2. Incumbent Candidate for Senate

The average senate incumbent raises more than $250,000, and senate candidates in tight races average $375,000. If you expect a hard-fought race and want enough budget for a campaign staff, lots of mailers, flyers, and yard signs, plus radio, television, and online ads, you may aim to raise $400,000.

That’s an ample but achievable budget. For example, in 2014 incumbent Pamela Roach raised $261,724 to successfully fend off competitive challenger Cathy Dahlquist. In a very tight 2014 race, incumbent Andy Hill raised over $1 million in his winning senate bid.

You are limited to $250,000 in Democracy Credits, so you’ll need to raise at least $150,000 from individuals and organizations. Successful incumbents in tight races in 2012 and 2014 raised an average of $85,905 from political parties, but the scenario below conservatively assumes the Credits lead you to rely more heavily on individuals.

Is collecting some or all the Credits from 2,000 people achievable? Yes. In 2014 Andy Hill reached 1,463 individual donors in his successful senate campaign. And collecting Credits will be much easier than raising actual money. In fact, many people will be looking for someone to whom they can give their Credits. Most senate candidates currently only collect contributions from 300 to 500 people, depending on parties and PACs to fill 70 to 80 percent of their war chests. Running with Democracy Credits will shift your campaign strategy away from big political players and toward everyday people.

Comments are closed.