In 2014, Tim Sheldon and Irene Bowling ran a tight race for the Washington State Senate seat to represent the state’s 35th District, covering Mason and parts of Kitsap and Thurston counties. In addition to the candidates’ own spending, Political Action Committees (PACs) spent over a million dollars attempting to influence the campaign. These expenditures pumped out political radio and TV ads for weeks.

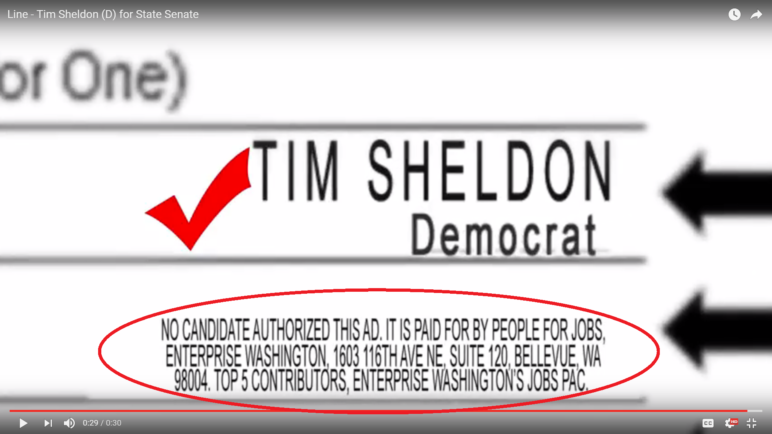

In accordance with current Washington requirements, all of these ads disclosed their top five contributors, but even these disclosures didn’t tell voters who was really behind the ads. For example, this ad in support of Tim Sheldon told voters that Enterprise Washington’s Jobs PAC funded the ad, but it failed to inform voters that this particular PAC consisted primarily of business and energy interests, including the Washington Association of Realtors, the Building Industry Association of Washington, and Puget Sound Energy. Naming these specific groups, rather than just a generically titled PAC, would have told voters a lot more about the types of groups that had an interest in Sheldon’s victory.

In our last article, we detailed how the Washington Government Accountability Act (WGAA), Initiative 1464 on the state’s November ballot, would crack down on the influence of big money in Evergreen State politics by reducing campaign contributions from lobbyists and state contractors, closing the revolving door between former public servants and lucrative lobbying positions, and tightening definitions of coordination between candidates’ campaigns and independent expenditures.

This article details additional ways that I-1464 would make Washington elections more ethical and transparent to voters. These provisions include more disclosure of the funders of political ads, a requirement that lobbyists file their monthly activity statements electronically to speed public accessibility, and the provision of dedicated funding to the perpetually under-resourced Public Disclosure Commission (PDC), the agency charged with monitoring campaign finance and election ethics for state elections.

I-1464 means more transparency in political ads

Current Washington State law effectively permits various political interests to mask their identities behind non-descriptive PAC names.

Masking donors: It happens on the left…

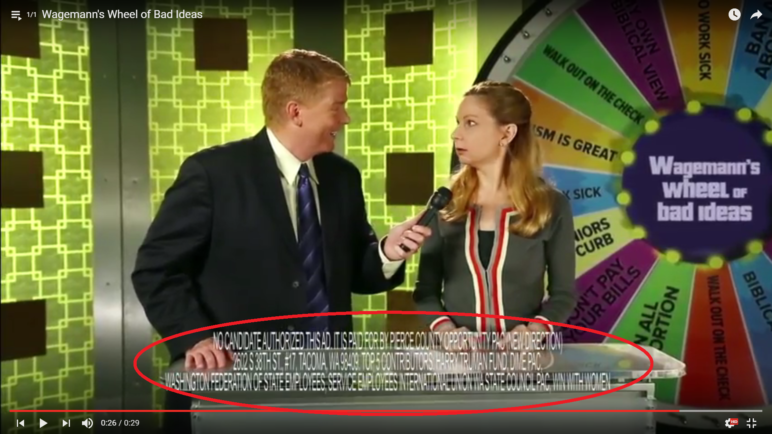

For example, this 2014 attack ad against Paul Wagemann, a candidate for the House District 28b seat (covering parts of Tacoma, Lakewood, and several other Pierce County cities), listed the top five contributors to the ad’s sponsor, Pierce County Opportunity PAC. All five of these contributors, though, are PACs themselves.

Most of these PAC names wouldn’t have meant much to average voters. For example, the Harry Truman Fund has no connection to the former president. In fact, the Fund’s main contributors in 2014 were the Washington Education Association union and the NextGen Climate Action Committee, a PAC almost entirely funded by California-based philanthropist Tom Steyer and dedicated to electing candidates committed to clean energy.

Similarly, DIME PAC, an acronym for the Washington state labor council’s Don’t Invest in More Excuses PAC, would have been difficult for Washington viewers to unpack. DIME PAC’s 2014 top contributors were unions and union-affiliated PACs. Finally, Win with Women’s top contributors were mostly individuals, but also included the SEIU Washington State Council PAC. Wagemann eventually lost the election.

I-1464 would require that political advertisements identify not just the top five contributors, but rather the top five contributing individuals or entities that aren’t PACs.

To help voters more easily comprehend exactly who is promoting or defaming any candidate for state government, the Washington Government Accountability Act would require that political advertisements identify not just the top five contributors, but rather the top five contributing individuals or entities that aren’t PACs. Had I-1464 been in place in 2014, the attack ad targeting Paul Wagemann would have listed not the Harry Truman Fund, DIME PAC, or Win with Women, but rather the top unions and individuals funding these groups, including Tom Steyer, the Washington Education Association, and the Washington State Council Service Employees International Union.

…And it happens on the right

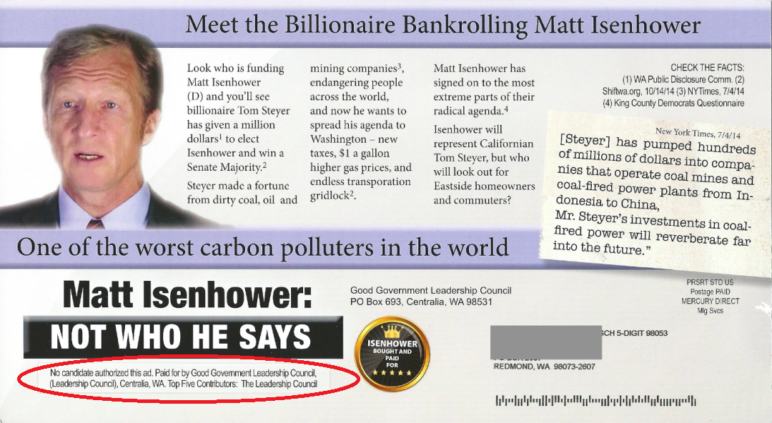

Masking the identities of political donors is a bi-partisan game, of course. Another example of attack ads with opaquely named funding sources were these 2014 mailers blasting three Democratic candidates for state legislative seats, including Matt Isenhower. They don’t disclose that they were paid for by out-of-state money from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and other business interests, including tobacco, gambling, and pharmaceutical companies.

Instead, they note that they were paid for by the Good Government Leadership Council, and this PAC’s top—and only—contributor was the Leadership Council. The Leadership Council’s top funder that year was the Republican State Leadership Committee (RSLC), which is a Washington D.C.-based PAC—an interesting irony, considering that these attack ads attack their opponents for receiving out-of-state funding.

So, voters must follow the complicated trail from the Good Government Leadership Council to the Leadership Council to RSLC, where finally, they will find those specific business interests listed above. RSLC’s top contributors included the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and business interests including tobacco, gambling, and pharmaceutical companies. Perhaps as a demonstration of the power of attack ads, all three of the targeted candidates lost their 2014 seat bids.

It even happens for state judge races

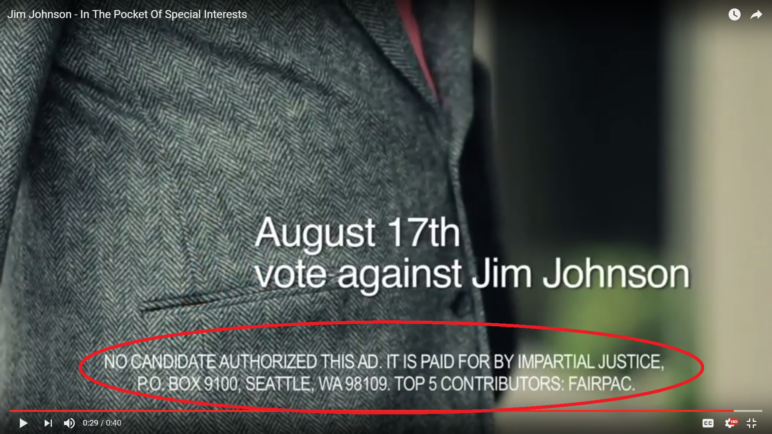

Hiding the special interests behind political ads is particularly troubling in elections for state judges, too. Arguably, the judicial branch should be furthest from the influence of special interests. The Brennan Center for Justice, a research center affiliated with New York University’s School of Law, scrutinizes judicial attack ads across the United States and flagged this 2010 attack ad against Jim Johnson, a candidate for Washington State Supreme Court Justice.

The ad was sponsored by the Impartial Justice PAC, which listed as its top contributor yet another PAC, FairPAC. Again, these generically named PACs gave Washington State voters little idea of who was funding the attacks. Digging deeper through archived reports on the PDC website, though, reveals that FairPAC’s top sponsors featured yet another set of PACs, including several unions, such as the Washington Education Association and the SEIU Washington State Council. I-1464 would have required Impartial Justice to reveal its union backers, clarifying for potential voters the specific interests that wanted to keep Johnson off the bench.

But I-1464 could restore the transparency voters need

To put it mildly, it’s quite a trip down a rabbit hole to untangle these nested levels of political ad funders. Journalists and researchers, and even more so the general public, would have to put in long hours to access even this basic information about who is really supporting or attacking certain candidates.

Had I-1464 been in place in 2014, it would have made tracking these contribution webs a great deal easier. So though Initiative 1464 unfortunately can’t put an end to attack ads, the measure would force PACs to be transparent about their backers, giving voters the opportunity to understand the true source of election ad propaganda.

I-1464 means electronic filing and easier public access to information

Initiative 1464 would also make the electoral process in Washington State more transparent by making information regarding lobbyists’ activities more publicly accessible. Currently, lobbyist reports are submitted in PDF format. To see the whole picture of who is giving how much to whom, and through whom, over the course of a year, one must download each PDF individually and enter the information into a spreadsheet by hand.

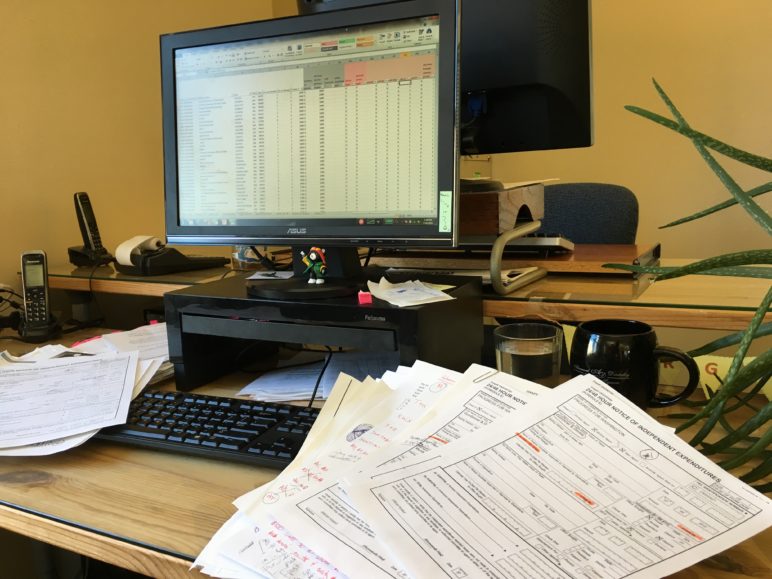

Such analog reports slow and hinder deep analysis regarding lobbyists’ activities and influence. For example, during Sightline’s own research for our previous article on I-1464, in which we detailed contributions to candidates that passed through top lobbyists’ hands, we had to sift through dozens of individual PDF files to track the contributions. Since each report amends and refers to other reports, we had to study each PDF to untangle the web of contributions. In short, this is what it looks like to trace political contributions in Washington state:

I-1464 would require that lobbyists’ reports with the PDC, including their registration and monthly activity reporting, be machine-readable on the PDC website starting in 2018. These reports would then be easily searchable via an online database, and journalists, researchers, and concerned citizens could quickly search, sort, compile, and compare lobbying data to bring important political contribution patterns to voters’ attention.

These reporting measures would make information more accessible to voters and also make other provisions in the initiative easier to enforce, such as those regulating contributions lobbyists handle on behalf of their employers. Especially in a tech-savvy state like Washington, such a minor requirement should be standard practice.

I-1464 means more support for Washington’s elections watchdog

The state’s Public Disclosure Commission (PDC) is the warden of Washington’s campaign accountability and transparency laws and the government body responsible for tracking and reporting campaign spending. The Washington Government Accountability Act charges the PDC with enforcing the additional rules outlined in I-1464.

Unfortunately, the PDC is persistently underfunded and understaffed. Local and national reporters have been writing about the need for more PDC resources for over a decade. A 2002 article written by the Center for Public Integrity, a nonpartisan, nonprofit investigative news organization focused on democracy and corruption, quoted PDC spokesman Doug Ellis saying, “Washington’s budget-writers leave the PDC understaffed and underfunded, year after year.” At the time that article published, Ellis was referring to a 25-member staff. Since then, the staff has been reduced to 19, even while the complexity and amounts of campaign, committee, IE, and lobbyist spending that the commission is supposed to track has skyrocketed.

I-1464 would empower the PDC by establishing the campaign financing and enforcement fund.

Chronic underfunding and understaffing prevents the commission from doing its job. In May of 2015, the executive director of the PDC, Andrea McNamara Doyle, resigned and released a letter explaining her decision. In it, she cited an insufficiently small staff, a prolonged and difficult period of downsizing, and antiquated technology.

A handicapped PDC probably contributed to Washington’s D+ grade in government accountability, transparency, and enforcement. The Center for Public Integrity’s annual report showed Washington state’s rank has fallen from second place in 2002 to eighth place in 2015.

I-1464 would empower the PDC by establishing the campaign financing and enforcement fund. The majority of these dedicated funds would support the democracy credit program (which we will describe in our next articles), but some would buttress the PDC’s ongoing work and help the agency to be able to do its job better on behalf of all Washington voters.

I-1464 boosts voter power—with the power of information

Initiative 1464 would increase transparency in Washington State by shedding light on the real funders of privately funded political ads, making political contribution information more accessible, and providing adequate funding to the PDC to effectively carry out its mission.

Armed with additional information and a robust oversight commission, more Washington residents could access the information that helps them learn more about their candidates, civically engage with their fellow citizens, and ultimately build a healthier democracy in the Evergreen State. In the following articles in this series, we’ll introduce another provision proposed by the Washington Government Accountability Act to empower voters and potential candidates.

[list_signup_button button_text=”Like what you|apos;re reading? Get the latest Sightline democracy research to your inbox.” form_title=”Reclaiming Our Democracy Newsletter” selected_lists='{“Reclaiming Our Democracy”:”Reclaiming Our Democracy”}’ align=”center”]

Comments are closed.