[Residents] might also ask why the city insists on ever-taller buildings and doubling or tripling density in single-family zones with accessory dwelling units, even though planners say current zoning has plenty of capacity.

So declared the Seattle Times editorial board, parroting one of the most persistent and ubiquitous arguments made during zoning debates far and wide, a rallying cry in neighborhood preservation circles not only in Seattle but in cities across Cascadia and beyond. “We have plenty of zoned capacity” is repeated credulously and earnestly by citizen activists and homeowners at city council meetings and community forums and in online debates (see here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here).

The zoned capacity argument is also false. It’s a myth. That’s what anyone who carefully looks into the numbers on zoned capacity and the methodology for estimating them can’t help but conclude.

What makes the myth plausible, though, is that zoned capacity—how many new homes could theoretically be built under zoning rules—is a real data point that Seattle and other cities estimate and publish. (You can find it here for Seattle and here for Portland, for example.) And these estimates invariably indicate that there is plenty of zoned capacity to accommodate projected population growth, leading people to wrongly assume that their city is making enough room for newcomers. Reaching that conclusion may be an understandable layperson mistake. For knowledgeable advocates, however, it’s more like malpractice.

In this article, I explain what zoned capacity actually is and detail what it reveals about the availability of sites for housing development. I focus on Seattle, but many of the same lessons apply across the Pacific Northwest and beyond.

“Zoned capacity,” in a nutshell

What is it, and how is it calculated?

The rules governing housing development are typically found in municipal zoning regulations that set maximum heights and other physical limits on building size and may also cap the number of homes allowed per lot. A critical question for any growing city is: does zoning leave room for enough new homes to meet the needs of residents, current and future?

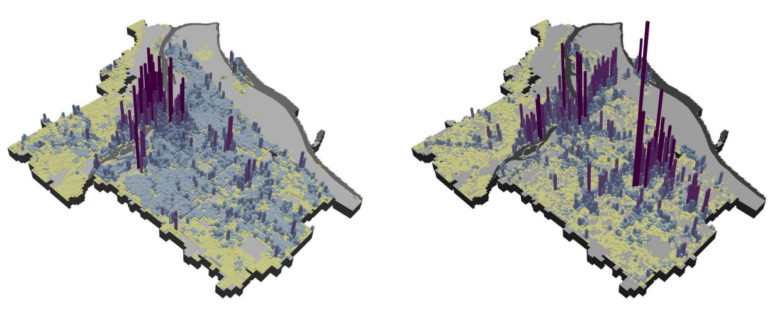

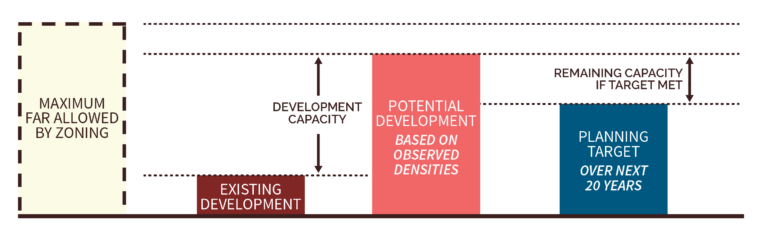

To answer that question, many cities assess how much new housing construction their zoning would allow. They generate estimates of “zoned capacity” (or “development capacity” or “housing capacity” or “buildable lands,” but I’ll call it “zoned capacity” throughout). You can think of zoned capacity as an imaginary city laid down over the existing one, with larger buildings on many parcels sprouting up from the current buildings. Zoned capacity is the sum of the additional apartments and houses in this imaginary city.

To estimate zoned capacity, planners do not simply tally the total number of living spaces that could be built under existing laws; they don’t assume every lot in town has been scraped bare and replaced with a new building holding the maximum permissible number of homes. Instead, they try to take into account what’s already standing on each parcel and what might be financially feasible to construct there, if anything. To get to their conclusions, they make a bevy of assumptions, and they extend the timeline into the distant future.

Seattle’s 2014 evaluation estimated that the city has a zoning capacity for 224,000 new homes, on top of the existing 308,000. Official population projections for the year 2035 anticipate an extra 120,000 people, in addition to the 684,000 already residing in Seattle in 2015. These figures and simple arithmetic give anti-growth voices all the ammo they need to push back on proposals for upzones, that is, changes to zoning to allow more homes. It makes for a powerful talking point, conveniently glossing over the fact that zoned capacity is exceedingly difficult to estimate correctly and is employed by planners only as a crude yardstick.

In a minute, I’ll go over the ways error creeps in. But first, a more important point—in fact, the most important thing to know about zoned capacity: in every city, zoned capacity is a side show to the main event. The main event is housing prices.

Housing prices are the crux of the matter. They reveal if people have enough housing choices. If vacancy rates are low and rents and housing prices are rising, then a city needs more homes. Period. The city needs to remove zoning-code barriers to more housing, so that builders can construct more homes. Compared with the evidence of the actual housing market, zoned capacity is just fuzzy math.

Compared with the evidence of the actual housing market, zoned capacity is just fuzzy math.

In Seattle, as in Portland, Vancouver, BC, and other tech-booming cities where housing prices and rents are spiraling upward, the gap between zoned capacity and actual home building demonstrates how inadequate are existing methods of estimating zoned capacity, as well as how misguided is the refrain that “we don’t need to upzone because there’s plenty of capacity.”

To preview the discussion that follows, here’s a summary of the key reasons Seattle’s zoned capacity estimate is misleading and does not justify halting upzones:

- The assessment overestimates zoned capacity. It ignores many real-world obstacles to housing development.

- Most of Seattle’s zoned capacity is in dense commercial areas, which are less family-friendly and more likely to expose residents to air pollution and automobile hazards.

- Seattle’s zoned capacity is shrinking as construction booms. The best building sites are already gone, and others are going fast. The faster a city grows, the sooner it makes sense to upzone and keep plenty of buildable sites available.

- Delaying upzones has the paradoxical effect of reducing future zoned capacity. Every building erected to four stories rather than eight, because zoning is too restrictive, represents four floors of potential homes denied to the city for as much as a century.

- Seattle’s population is growing much faster than projected.

Cities in Washington, as in Oregon, are required by their respective states’ growth management laws to assess their zoning and ensure that it allows sufficient development capacity to meet regional growth targets. To derive its estimate, Seattle first excludes properties unlikely to ever redevelop, such as cemeteries, churches, and schools. From the remaining parcels of land, the city identifies those that are likely to redevelop using one of two measures, depending on the location:

- Development Ratio: the existing homes on the parcel compared to the number of units that could be built under current zoning. The more units that could be built, the more likely redevelopment will occur. For example, a single-family house on a parcel where an eight-unit apartment building is allowed would have a development ratio of one to eight.

- Improvement to Land Value Ratio: the value of buildings and other improvements on a parcel compared with its land value, according to King County’s property-tax assessments. The lower the ratio—that is, the more valuable the land is, relative to whatever structures stand on the site—the more likely redevelopment will occur. A run-down, one-story commercial building in a neighborhood zoned for six-story apartment buildings might have a ratio of one to three, because the land’s redevelopment potential is worth three times as much as the building.

Lastly, for all the parcels flagged as likely to develop, the city applies assumptions extrapolated from historical trends to project how many homes would be built there.

Applying this methodology to 2012 data, Seattle estimated a zoned capacity of nearly 224,000 additional housing units. That’s enough to accommodate more than three times the city’s adopted growth target of 70,000 new households over 20 years. But does that really mean there’s more than enough land for new housing construction and no upzones are needed? Nope.

The numbers are wrong: Why Seattle’s zoned capacity estimate is too high

1. It ignores how buildings actually get built.

Seattle’s zoned capacity estimate is an abstraction disconnected from the on-the-ground realities of real estate development, as acknowledged in the city’s own definition:

[Zoned] capacity is an estimate of how much new development could occur theoretically over an unlimited time period under current zoning. [Zoned] capacity is not a forecast of how much or when development will occur.

Two phrases stand out: “over an unlimited time” and “not a forecast of how much.” Basically, zoned capacity is not the same thing as capacity that is actually buildable, certainly not within the next 20 years. Multiple factors not accounted for in the city’s estimate influence whether or not housing gets built. Seattle planners call out the following limitations:

- Financial feasibility: Home prices and rents change by location, and construction costs depend on the housing type—and both of these factors vary over time. A substantial share of “zoned capacity” is unprofitable to build: the rents won’t cover the construction costs.

- Demand for a particular type of housing: If there is little demand for the housing type assumed by the capacity estimate, then developers may choose either to build a higher-demand type that doesn’t use all of the theoretical capacity or to not build at all.

- Landowner’s willingness to sell or redevelop: Owners may have a variety of personal, unpredictable reasons for not selling or redeveloping a property, regardless of whether it has capacity according to the city’s estimate.

The willingness-to-sell factor compounds when housing projects need multiple parcels of land, which is usually the case for all but the smallest buildings. To assemble a big enough site, developers must cut deals with several property owners. Each land sale is subject to the whims of each owner, so the more pieces that have to be put together, the lower the likelihood of success. One unwilling seller can block new homes on two, three, or even more parcels that the city’s methodology has nevertheless counted as contributing to zoned capacity.

Zoned capacity is not the same thing as capacity that is actually buildable, certainly not within the next 20 years.

Another factor left out of Seattle’s capacity estimate is neighborhood opposition to new housing projects. Pushback from residents can introduce enough uncertainty and delay to literally scare developers away from otherwise workable sites. Three recent cases illustrate some ways zoned capacity overstates what home builders can actually do when neighbors mobilize against them, causing exceedingly drawn-out approval processes, whittling down of building size and housing units, and even the mid-stream abandonment of projects.

For all these reasons, Seattle’s estimate of zoned capacity is too high. If a crystal ball could reveal—through all the shifting complications of time and space, construction costs and real-estate markets—a reality-based zoned capacity, it would far less than 224,000 new homes. If that crystal ball could also reveal the appropriate figure not for all time but just for the next 20 years, the zoned capacity would be a fraction of that number. And that’s the primary reason why housing prices are soaring in Seattle: demand for homes is surging past the limited space to put them, causing economic displacement of longstanding communities and shutting out hopeful newcomers before they can even say “Emerald City.”

2. It ignores that Seattle is using up its “lowest hanging fruit” zoned capacity and neglecting future capacity needs.

Dynamic factors add to the distortion of zoned capacity estimates. First, zoned capacity gets consumed by construction. The sites that are easiest to redevelop go first, and unless cities upzone to keep pace, land on which building is feasible grows scarce. This scarcity slows the production of housing, driving up prices. To prevent this logjam, policymakers can implement ongoing upzones to retain an ample zoned capacity “budget.”

Second, delaying upzones annihilates future zoned capacity. By design, zoning often forces developers to plan buildings that are smaller than what they would have built were they only responding to the number of home-seekers who can afford to pay the rent. That is, many of Seattle’s new housing projects would have included more homes if zoning didn’t prohibit it.

Adjacent to downtown Seattle, in the Capitol Hill neighborhood, for example, high-rise housing construction is financially feasible, but height limits preclude it, depriving the city of thousands of new homes. Every new apartment building erected there that’s shorter than housing demand would have made profitable is an opportunity lost for the life of the building, which could be 100 years or more. In metropolitan centers such as Seattle, delaying upzones depletes future zoned capacity.

3. It relies on a too-low population projection.

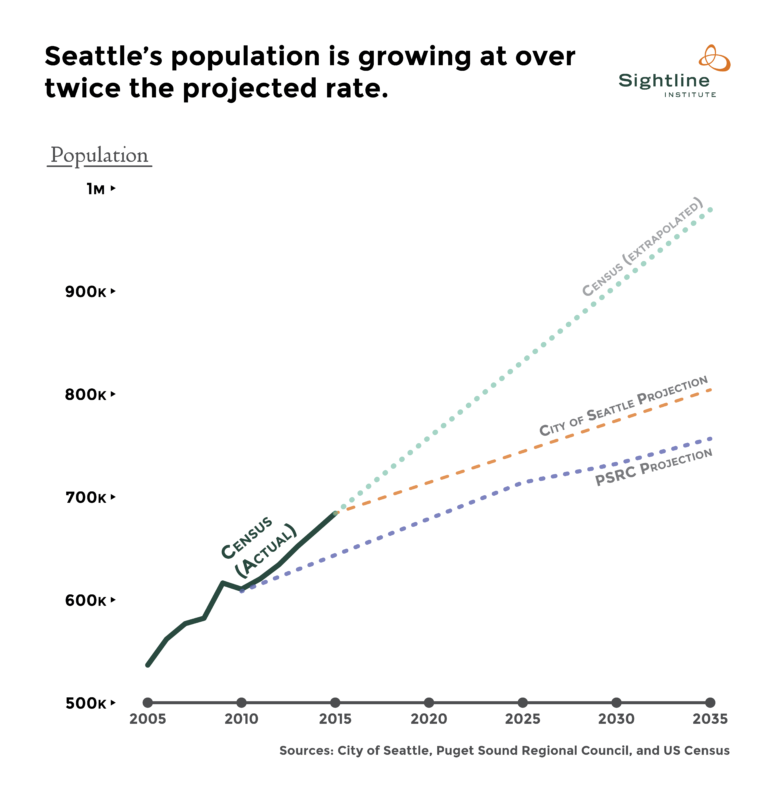

The “plenty of zoned capacity” myth is wrong not only on the supply side. It’s also likely wrong on the demand side, as illustrated in the graph below.

The official growth projections published by the City of Seattle and by the Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC) are both far below the actual rate of growth over the past decade, according to the US Census. Linearly extrapolating the 2005-2015 growth rate yields a population of about 979,000 in 2035, corresponding to a gain of 172,000 households (assuming the city’s projected household size of 1.7). That’s two and a half times the official forecast of 70,000 new households, and over three quarters of the (too-high) capacity estimate of 224,000 housing units (for a visual illustration of the implications, see the zoned capacity analysis diagram above).

Seattle’s population growth in recent years has been high compared with historical norms. Few predicted such off-the-charts job growth in the tech sector, with Amazon alone spawning new office buildings that could eventually hold some 65,000 employees. Over the longer term, Seattle’s temperate climate makes it a possible destination for climate refugees, which could bring additional residents.

Linear extrapolation is a blunt projection method that may overestimate future growth. However, it does demonstrate that Seattle’s assumptions about the future need for zoned capacity could be much too low. When equitable access to opportunity for so many is at stake, policymakers would do well to err on the side of providing extra zoned capacity.

The values are wrong: Seattle’s zoned capacity does not promote equity

1. The capacity is not zoned as a shared responsibility across neighborhoods.

Seattle’s zoned capacity estimate is further flawed by ignoring where in the city new housing can go. Current zoning doesn’t make room for new homes in the right places, the places that offer the best opportunities, the places people most want to live.

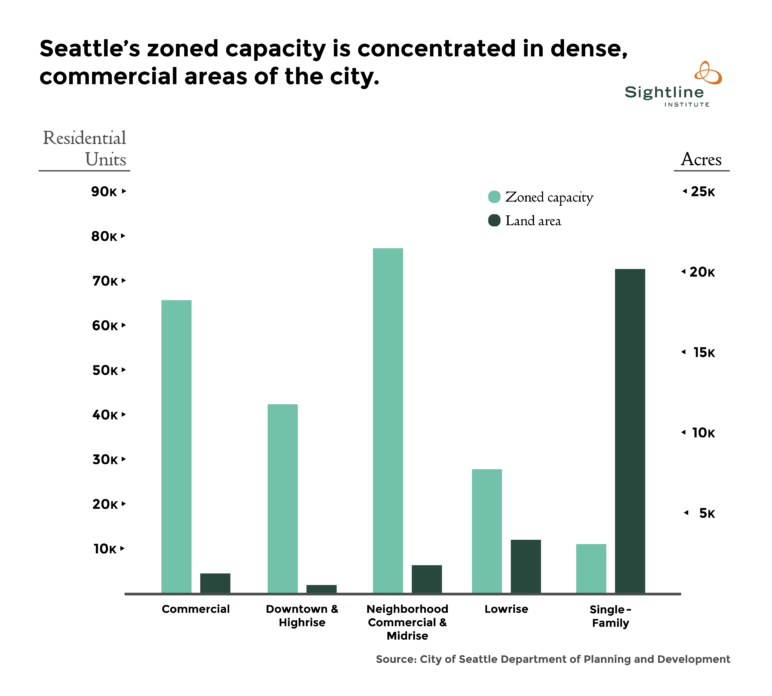

Some 77 percent of Seattle’s zoned capacity for housing is in the city’s urban centers and villages. These relatively dense, transit-rich commercial centers range from the downtown core to neighborhood business districts. And Seattle policy singles out these centers for upzones in order to create even more capacity:

While the city may have enough [zoned] capacity overall, upzones may be proposed… where the potential for job and housing growth increased because of transit investments. Upzones may… encourage residential and job growth in urban centers and villages.

But this policy effectively dictates that any future expansion of the city can only occur in areas with predominantly multifamily housing around busy streets. These places may be great for some Seattle residents, who perhaps prioritize access to lively street-life corridors or proximity to their workplaces. But what about lower-density areas that may offer greater access to amenities such as parks and good public schools, or that provide a quieter, more family-friendly environment?

The figure above shows how zoned capacity is distributed among Seattle’s zoning categories, along with the total acreage of parcels in each zone. Areas where higher-density housing is allowed—the commercial, downtown, highrise, neighborhood commercial, and midrise zones— hold almost all the city’s capacity. Together these zones provide fully 83 percent of the city’s capacity, though they cover just 13 percent of the city’s housing land (that is, land on which housing can be built, which excludes industrial zones, city-owned parks, and other land where housing is not allowed).

Areas where higher-density housing is allowed hold almost all the city’s capacity. These zones provide fully 83% of the city’s capacity, though they cover just 13% of the city’s housing land.

Lowrise zones cover 12 percent of the city’s housing land and yield 12 percent of the city’s zoned capacity. Townhouses, rowhouses, and single-family clusters are the most common lowrise types, also known as “missing middle” housing that fills the gap in scale between single-family houses and large apartments and condos.

Lastly, single-family zones cover a whopping three-quarters of the city’s housing land but contribute just 5 percent to the city’s zoned capacity.

Current zoning mandates that most of Seattle’s new homes will be apartments in the city’s most built-up areas. Is that an outcome that supports the city’s stated goals for diversity and equity, for every neighborhood doing its part to support Seattleites old and new?

2. The capacity is not zoned as family-friendly or environmentally just.

Just 19 percent of Seattle households have children—of all major US cities, only San Francisco has fewer. In response, city authorities established a goal to “promote households with children and attract a greater share of the county’s families with children.”

The disconnect is hard to miss. Seattle’s zoning severely restricts the construction of the kind of new housing that is desirable to most families with children. Advocates lament the construction of so many small apartments suitable only for singles and childless couples, but that’s exactly what city zoning mandates: thousands of apartments, and few duplexes, triplexes, townhomes, or cottages. (Of course, building small apartments does help families indirectly. It frees up larger houses for families with children by creating more options into which empty-nesters can downsize or young singles or couples can live.)

The City of Seattle is currently debating policy to address environmental justice concerns about “the health impacts of rezones to allow or increase residential development adjacent to… sources of air pollution such as transit and freight corridors and highways, and industrial areas.” But the city’s zoning has already relegated most of the capacity for new housing to busy commercial areas and arterial corridors that are likely to expose residents to more air pollution compared with single-family neighborhoods. Likewise, living near busy roads increases the risk of getting hit by cars, an especially grave concern for children and the elderly.

Concentrating new housing growth in high-density areas also reduces equitable access to parks. The city has not published data on park access broken out by zone, but the general pattern that is observable in maps, along with the limited data available, strongly suggest that the people living in single-family zones are more likely to be near the city’s best parks and open spaces.

Single-family zones cover a whopping three-quarters of the city’s housing land but contribute just 5 percent to the city’s zoned capacity.

About 90 percent of city-owned parks and open space are zoned single-family (albeit some parks are located adjacent to zones that allow multifamily). In 2012, there were 8.9 acres of park per 1,000 residents citywide; in contrast, the city’s goal for urban centers and villages is just 0.5 acres per 1,000 residents. The City’s 2011 Gap Analysis Update—a report on open space accessibility or lack thereof—found gaps in the distribution of useable open space in almost half of the urban centers and villages throughout the city.

Not only does the lack of zoned capacity in single-family zones drastically limit the number of people who can enjoy the benefits of living in them, but it also locks in a high cost of entry. Detached single-family homes are the most expensive form of housing in the city, on average, yet city laws allow only this inherently unaffordable type of home on three-quarters of the housing land. The result is economic exclusion.

There is a straightforward fix for the above-described affronts to diversity, social justice, and affordability: make more room for missing middle housing in single-family zones. And that’s exactly why Seattle’s Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda (HALA) recommended legalizing duplexes, triplexes, cottages, and small apartments in all single-family zones, as long as they conform to existing restrictions on the physical form of single-family houses. The backlash against that proposal is now legendary, with opponents citing the city’s own zoned capacity estimate as a reason to leave single-family zones untouched.

HALA also recommended eliminating barriers to accessory dwelling units in single-family zones and upzoning about 6 percent of the city’s single-family land—all the single-family land that’s a) inside of urban villages, b) adjacent to those villages and within a 10-minute walk of frequent transit service, or c) backed up to mid-rise development along arterials with frequent transit service. It’s a small ask of high-opportunity single-family neighborhoods, but its impacts would be great. Implementing all these recommendations would help rectify the imbalance between the location of the city’s zoned capacity and city’s goals for equity, affordability, family-friendliness, and social justice.

Conclusion

Zoning that limits how many people can live in a place is a definitive feature of modern cities. But in fast-growing cities such as Seattle, making room for more homes is essential to preventing economic displacement and creating an equitable and environmentally sustainable city. This tension is the prime urban planning challenge of our era.

Addressing this challenge hinges on a clear understanding of the amount of new housing allowed by zoning. Unfortunately, assessments of zoned capacity tend to frame the debate around the idea that growth is at best a necessary evil, and the results all too often end up as fodder for opposition to opening up the city to more people.

Seattle’s estimated zoned capacity for new homes is enough to accommodate three times the official projection of new residents over the next 20 years. Any reasonable novice would ask, “Why upzone?” But experts should know better—zoned capacity doesn’t mean what most people think it means. However, that doesn’t stop the myth from proliferating and from fanning the flames of popular resistance to upzones.

As detailed in this article, estimating zoned capacity is a theoretical exercise that ignores many of the factors that determine whether or not housing gets built: timeline, fluctuating costs and prices, unwilling sellers and the challenges of parcel assemblage, mismatches between zoning and demand, neighborhood opposition that delays or shrinks or scares away new housing, concentration of zoned capacity in dense districts with worse air and traffic and that are outside of the most desirable neighborhoods.

Zoned capacity also gets consumed by new construction itself, especially when zoning causes smaller buildings with fewer homes to be built, which locks in housing shortages in desired locations for decades. And lastly, in Seattle’s case, the “plenty of zoning capacity” myth implodes not only because the estimate itself is so flawed, but also because the city’s population is growing twice as fast as planners projected.

But as I noted at the outset, zoned capacity is a sideshow, a technical curiosity. Invoking zoned capacity as an argument against more homes for people in Seattle or any other growing city reveals nothing so much as the misunderstanding of those making the argument.

Zoned capacity is not plentiful in Seattle. If it were, housing prices wouldn’t be going through the roof. The fact that housing prices are skyrocketing is the smoking gun of our severe shortage—no matter what the Seattle Times editorial board and platoons of earnest anti-builder activists say.

[list_signup_button button_text=”Like what you|apos;re reading? Get the latest Sightline housing research right to your inbox.” form_title=”Housing Shortage Solutions Newsletter” selected_lists='{“Housing Shortage Solutions”:”Housing Shortage Solutions”}’ align=”center”]

Comments are closed.