Low-income families typically cause far less greenhouse gas pollution than their better-off peers; yet because they make less money, they spend a larger share of their income on carbon-based fuels. They’ve done the least to cause climate change, but they’re the most vulnerable to its impacts. They’re also most vulnerable to the single best policy for taming carbon pollution—putting a price on it—which would hit them in the pocketbook harder than anyone, relative to their incomes.

Moreover, they have fewer opportunities to unplug from fossil fuels: they often live in drafty old buildings whose heating systems and insulation levels they do not control; what housing they can afford is, increasingly, far from jobs, transit, good schools, and other services; and if they have cars, they cannot afford electric ones. More than anyone else, therefore, low-income households deserve at least to be held harmless during the transition to clean energy and preferably to get a helping hand to make the transition.

How to do that is easier said than done, especially in the Northwest states. As we’ve recently published, Oregon’s Healthy Climate Bill earlier this year argued for a climate equity approach borrowed from California, which would have proved an awkward fit for Oregon and left behind many of its intended beneficiaries. The draft climate policy proposal of Washington’s Alliance for Jobs and Clean Energy calls for the same California model. And Washington’s Initiative 732 leaves some hundreds of thousands of low-income households partially unsheltered from the costs of the clean energy transition.

So how could Northwest policymakers better ensure that low-income families benefit from a smart carbon pollution price? Sightline has a novel idea… that may in fact sound helpfully familiar.

What are Green Stamps?

Here, we propose a way to ensure that no low-income families are harmed and most are actively helped by a steadily rising price on pollution: send each of them “Green Stamps.”

Like food stamps (or the old customer-loyalty S&H Green Stamps that were popular in the United States until the 1980s), Green Stamps would be coupons that families could use for any qualifying purchase. Qualifying purchases would include just about anything that advances climate and clean energy solutions. State authorities would finalize the list of approved goods and services, but it might include things like:

- transit passes,

- car-sharing trips,

- energy efficiency upgrades to home or appliances,

- utility green power plans,

- utility bills from zero-emissions utilities,

- bicycle purchases or repairs,

- fuel-saving car tune-ups,

- fuel-saving car tires,

- biofuels,

- leasing or buying a super-efficient or electric vehicle,

- healthy local food from a community-supported agriculture farm, farmers’ market, or local grocery,

- solar panels,

- solar water heaters,

- train or long-distance bus tickets,

- job training in a green field,

- low-energy cooling devices, such as fans, and

- clotheslines.

People could also contribute Green Stamps to neighborhood, school, and charitable funds or to community-based organizations to spend in highly impacted areas on local community projects, such as:

- tree planting,

- shared electric vehicles,

- walking and cycling infrastructure,

- bus stop infrastructure,

- increased transit frequency,

- energy-efficiency retrofits of public and nonprofit buildings, and

- solar power on the roof of a community church.

Who could qualify to receive Green Stamps?

In principle, Green Stamps could go to every resident of the state—a variant of the “Cap and Dividend” approach to pricing carbon. But a targeted, and cheaper, plan would sidestep a potential legal barrier to dividends in Washington by delivering Green Stamps to all residents who already qualify for means-tested or hardship-related federal or state government programs, such as unemployment insurance, free and reduced-price school lunch, food assistance, and energy assistance.

For example, food stamps—officially called the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)—reach more than 1 million Washington residents, or about 15 percent of the state’s 7 million people. WorkFirst, Washington State’s temporary cash assistance program, reaches about 20,000 adults and 15,000 children. In Oregon, SNAP reaches around 300,000 households, or nearly 20 percent of Oregon’s 1.7 million households.

How could states administer Green Stamps?

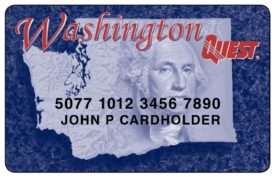

Some might wonder about the added administrative cost of a Green Stamps program. But Northwest states could easily and cheaply piggy-back on Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) cards, which are already widely used to distribute existing means-tested benefits, such as food stamps. People use the Oregon Trail Card and the Washington Quest Card just like a debit card to purchase approved food items. The Washington card also handles cash benefits, and other states use a single EBT card to issue benefits from multiple programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) and low-income cash assistance.

Trafficking—selling food stamps for cash—is the most common type of food stamp fraud, but it impacts less than 0.5 percent of food stamps. Still, this type of fraud would not be a critical concern for Green Stamps, because even if some recipients sold their stamps for cash, the program would still achieve its twin goals: assisting Oregon and Washington’s low-income residents and directing money towards clean energy and climate solutions. The person purchasing the green stamps could still only spend them on things like energy efficiency retrofits, riding the bus, or green job training, and the low-income family would get the cash it needs for other goods or services. That’s not a bad outcome.

Why opt for benefit recipients over geography to qualify?

As we mentioned, some social justice advocates favor California’s approach to equity—that is, investing carbon pollution revenue in disadvantaged neighborhoods. And we noted that Sightline’s recent report about climate justice in Oregon outlines how awkwardly California’s climate justice approach would fit the Beaver State: investing only in certain census tracts would effectively neglect the neighborhoods where the majority of low-income families and people of color live. Furthermore, even within beneficiary neighborhoods, investing in community-based projects might leave hundreds of thousands of individual households worse off.

For example, let’s say a climate policy, instead of cutting the sales tax as Washington’s I-732 would do, dedicated about one-quarter of all the carbon revenue—$500 million per year, minus some funds for administering the program, so say around $450 million—to investments in disadvantaged communities. If an oversight committee directed all of the money, say, to install rooftop solar arrays, at $10,000 per roof, within qualifying census tracts, it could reach 45,000 households per year. Many low-income households would not be within the qualifying census tracts, but even if they were, it would take almost 18 years to reach all 800,000 low-income households in Washington. The families who received the solar panels might save around $500 per year on electricity bills (low-income families wouldn’t qualify for federal solar tax credit), but their neighbors and friends without solar panels would fall behind each month as they paid more for energy but received no benefit. Weatherizing low-income homes, often lauded as a cheaper and lower-tech energy-use reducer, would similarly be beneficial, but again, on the census tract model, it would not reach all low-income households nor completely compensate those that it reached for increased energy costs.

Or say the committee used the carbon revenue to build affordable, transit-oriented housing. The families who lived in such housing would gain substantially and the surrounding neighborhood overall would benefit from the existence of affordable housing that relieved housing pressure and from convenient transit that relieved congestion. But $450 million per year would build only about 1,500 affordable units (at $200,000 per apartment, a common rate for subsidized units): a drop in an ocean of need. And again, the other 798,500 low-income families would incur direct monthly costs from the carbon price and no direct benefits from the revenue.

Even one of the most broadly beneficial potential investments—public transit projects—would still fall short of equity. For example, Washington could invest more in Bus Rapid Transit (BRT)—bus lines that provides similar service as rail at a fraction of the cost—to give tens of thousands of people a convenient option for getting around while also reducing pollution and easing congestion on crowded corridors. BRT lines are huge boons to the people who ride them and to their neighborhoods more generally because they improve access to jobs.

But investing the polluters-pay revenue in BRT would still only benefit some members of the community. Public transit commuters, on average, make less money than their car-commuting counterparts. Even in the relatively transit-rich Seattle metropolitan area, 74 percent of employees earning less than $15,000 per year commute by car, and statewide in Washington, 85 percent of households living in or near poverty own a car.

So, say the committee spent $35 million per BRT line to outfit ten new RapidRide bus routes plus $2 million per year to operate each. Together, say the ten lines served 100,000 riders per day, and say three-quarters of riders were low-income. Each year, the committee could build fewer new lines because more money would need to go to operating existing lines, so after five years of dedicating all the polluters-pay revenue to building and operating bus lines, the program would directly benefit fewer than 375,000 people, leaving around 1,625,000 low-income Washingtonians worse off.

We’re not arguing against any of these clean energy investments. We’re just saying that they cannot shelter all low-income households from a carbon price, nor can they help all low-income households move beyond carbon. They’re good projects; they’re just a bad safety net.

But Green Stamps could be a good fit for the Pacific Northwest

Green Stamps would be a more equitable use of carbon revenue than investments that only benefit certain individuals or households within certain census tracts. Or Green Stamps could provide the safety net while other resources go to transit, affordable housing, and renewable energy. Or Green Stamps could combine with other policies such as Washington’s Working Families Tax Credit or utility bill climate credits, such as California issues, to further shelter low-income families both from carbon pricing and from the worst effects of climate change.

For example, if Washington voters approve I-732 in November, some share of 340,000 low-income households will come out behind in financial terms: sales tax reductions will not compensate them fully for increased energy costs. But the state legislature, or voters themselves, through a future initiative, could use Green Stamps to fill this gap in coverage. Green Stamps could provide monthly benefits to all families who qualify not only for the Working Families Tax Credit but also for SNAP, WorkFirst, free or reduced-price lunches, or other means-tested programs. Some 57 percent of the more than one million Washington SNAP recipients do not qualify for the Working Families Tax Credit.

Similarly, more than half of the 780,000 Oregonians receiving food stamps do not qualify for the modest state Earned Income Tax Credit. If Oregon used carbon revenue to expand the state credit, it would still need Green Stamps to ensure non-qualifying needy families benefit from the pollution price.

Green Stamps would also be a powerful addition to the draft policy of Washington’s Alliance for Jobs and Clean Energy and to the next incarnation of Oregon’s Healthy Climate Act. In both cases, climate justice advocates have mostly focused on emulating California’s geography-based approach, dedicating a portion of the carbon revenue to projects located in the state’s most highly-impacted census tracts (California dedicates 25 percent, while Oregon’s 2016 bill would have dedicated 40 percent). Dedicating a similar amount of money, but sending it directly to disadvantaged households instead of disadvantaged census tracts, could ensure that every low-income household comes out ahead and gets a big help in moving beyond carbon.

In Washington, the $450 million described above could give all 800,000 low-income Washington households $560 per year in Green Stamps to spend or to pool. Or, if Washington dedicated 40 percent of the carbon pollution revenue to Green Stamps and sent more money to the poorest families, it could send around $1,500 per year to roughly 360,000 households living in poverty (a parent and two children living on $19,530 or less) and about $600 per year to the remaining 440,000 low-income households (a parent and two children living on $39,060 or less).

Oregon, unfortunately, faces constitutional barriers to spending carbon pollution revenue on transit, trees, and efficiency. However, if Oregon could manage to amend its state constitution, it could issue Green Stamps at similarly beneficial levels.

Conclusion

Sightline is committed to ensuring a carbon pricing policy equitably benefits people who are hardest hit by the climate gap. A household-based approach might be more equitable in the Northwest than California’s census tract-based approach because it would benefit all identifiable disadvantaged households, not just some of them.

Moreover, it would give every low-income household a role in the decision-making about those benefits—whether to spend them on transportation, energy, food, or community projects. Small public grants to community-based organizations, too, could enable them to help community members spend their Green Stamps wisely. A model like this—giving poor people, as well as the organizations based among them, leading roles in steering the clean energy transition—could elevate the voices and interests of historically marginalized communities and in turn help build their lasting influence at the public policy table.

[list_signup_button button_text=”Like what you|apos;re reading? Get the latest Sightline democracy research to your inbox.” form_title=”Reclaiming Our Democracy Newsletter” selected_lists='{“Reclaiming Our Democracy”:”Reclaiming Our Democracy”}’ align=”center”]

Comments are closed.