Portland needs to repair potholes and improve street safety. #PatchPDX

If you live in Portland, you have your May ballot in hand. Don’t just pick a presidential candidate and mail it in. Keep going: past all those unopposed judicial positions, yes, all the way at the bottom of the second page you’ll find “Measure 26-173: Temporary Motor Vehicle Fuel Tax for Street Repair, Traffic Safety.” You might not know it from this well-below-the-fold placement, but it’s important for sustainability, livability, climate change, and good local governance. Here’s what you need to know.

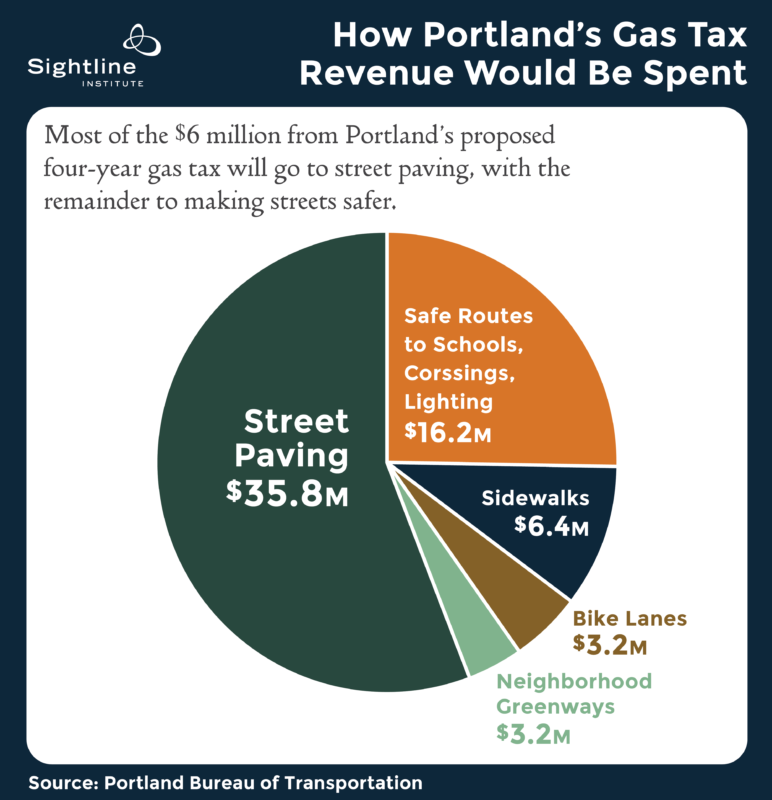

A yes vote on Measure 26-173 would approve a four-year, 10-cent-per-gallon city gas tax that could raise $64 million over the course of those four years. The city will use a majority of the revenue for much-needed repair to and paving of city streets. And a little less than half of the revenue will go to projects that make streets safer—particularly improving routes to schools, investing in neighborhood greenways, and upgrading the intersections where people are most likely to be killed or injured. Those are investments that benefit all Portlanders.

If you care about sustainability, you might like the Portland gas tax

Vibrant, affordable, livable, well-run cities are key to our sustainable future. To keep things running smoothly, cities need to spend money building and maintaining a safe and efficient transportation system. The City of Portland has, sadly, been underfunding streets for decades. And it shows. More than half of local streets are in poor or very poor condition.

Even more frightening for a city that aims to be a multi-modal mecca of sustainability, Portland’s streets aren’t safe. In fact, Portland’s streets are less safe than they were a decade ago. More people per total population are killed on Portland streets than in New York, San Francisco, or Seattle. To rescue Portland’s vibrant, sustainable identity, the city needs to repair potholes and improve safety. The gas tax will enable the city to get a start on some of that much-needed work.

If you care about climate change, you might like the Portland gas tax

Oregon’s biggest source of greenhouse gas emissions is the transportation sector. One key to cutting transportation emissions is to empower people to get around without an internal combustion engine. For longer trips, this might require an electric bus or car, but many trips are short.

Nationwide, nearly half of all trips are three miles or less, and in a city with lots of 20-minute neighborhoods, probably even more trips are hyper-local. Able-bodied people could walk or bike for those trips if they felt pretty sure they could do so safely, including kids who could opt to walk or bike to their neighborhood school. By improving safe routes to schools and upgrading the city’s most dangerous intersections, the city can empower Portlanders and Portland kids to go by foot or bike. In short, safer streets mean more people walking and biking and less pollution.

If you care about equity, you might like the Portland gas tax

People of color in the Portland area drive less than white people. Nationwide, higher-income households spend about four times as much money on gas as do lower-income households. So lower-income Portlanders and households of color will likely pay less for the gas tax than higher-income white households. The tax will cost the average Portland household about $5 per month, but it will cost many lower-income households about half that amount, and higher-income households about twice as much.

However, low-income households still pay more for gas as a percentage of their income than do higher-income households, so the gas tax will still hit them harder relative to their income. Low-income advocates worked with city commissioners to ensure that this regressivity is offset by much-needed investments in low-income communities.

The burden of under-investment in streets, in the form of poorly maintained streets and avoidable injuries, falls disproportionately on low-income Portlanders and communities of color. Most of the city’s dangerous “high-crash corridors” run through east Portland. Affordable housing advocates, including Oregon Opportunity Network, Community Alliance of Tenants, Portland Community Reinvestment Initiatives, Orange Splot, OPAL – Environmental Justice Oregon, and ROSE Community Development all support Measure 26-173, because the money will improve streets and safety in the neighborhoods that need it most.

If you care about livable neighborhoods, you might like the Portland gas tax

Many cities in the western United States are built around the needs of cars rather than people, and these places are paying the price in the form of sprawl, pollution, lack of access, noise, injuries, and deaths. Portland has been trying to buck the trend and build for people, but the growing potholes and worrying uptick in injuries signal the need for Portland to make a renewed commitment to livability. The gas tax is a step in the right direction, enabling the city to maintain infrastructure and preserve livability.

If you care about local solutions, you might like the Portland gas tax

State and federal legislators can’t seem to bring themselves to authorize gas taxes that keep up with inflation, much less increase taxes to meet the needs of changing transportation patterns. Congress hasn’t increased the federal gas tax in over two decades; it is still languishing at 18.4 cents per gallon. Oregon legislators have been more responsible, increasing the state gas tax regularly throughout the 1980s. However, the current 30-cents-per-gallon state tax buys fewer road repairs than the 24-cent-per-gallon tax did in 1993.

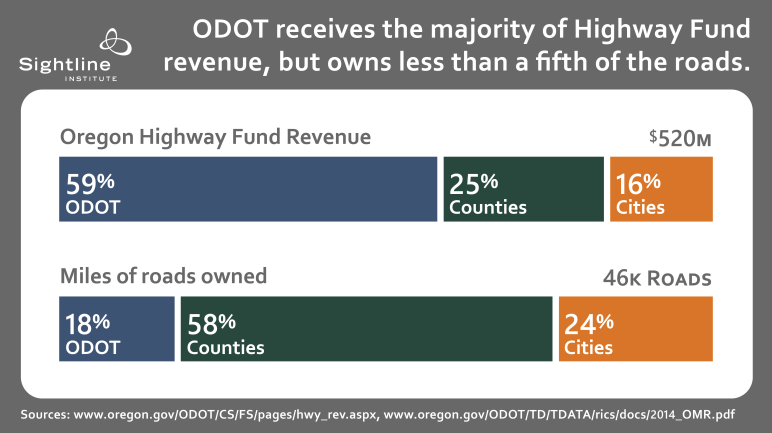

The Oregon state legislature also sends most of the gas tax revenue to the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT). Only 16 percent of the revenue comes back to cities, which need more cash to invest in prudent repair and maintenance of local roads. Cities can’t depend on federal and state coffers to keep local roads in good repair. Two counties and twenty-one cities (Troutdale just approved a city gas tax in November) have taken matters into local hands and enacted local gas taxes to repair local streets. Portland could do the same.

If you care about fiscal responsibility, you might like the Portland gas tax

Decision-makers face hard financial calls all the time, but some tradeoffs just determine which thing will get funded this year and which will have to wait until next. With street maintenance, unfortunately, every year of delay doesn’t just kick the can down the road; as this City Club of Portland report points out, it grows the problem at an accelerating rate (full disclosure: I was the lead author of this report). One dollar in street repairs delayed can grow to $10 in repairs just a few years in the future. Infrastructure maintenance doesn’t sound thrilling or urgent, but maybe Edward Norton’s new movie will amp up your excitement for this inarguably necessary investment.

Did someone just say “expensive bureaucracy”? Not so fast. Because Oregon already collects and distributes revenue from a gas tax, Portland won’t have to set up a new collection mechanism. Administrative costs will be low, and compliance will be high. Avoiding ballooning future costs and keeping overhead low: the gas tax is a frugal accountant’s dream.

If you harbor an inner economist, you might like the Portland gas tax

Last year, brilliant local economist Joe Cortright laid out some guidelines for how Portland should pay for streets. He advised Portlanders to employ the “user pays” principle so that those who use streets more will pay more, and anyone can change the amount they pay by using less. With the exception of electric vehicles, a gas tax adheres to the “user pays” principle. Similarly, Cortright recommended rewarding those who drive less because they are helping the whole transportation system work better.

Portland is growing; if the car population grows as fast as the people population, the city and its streets will truly be in trouble. The gas tax creates a small carrot for those who get around car-free. Cortright also warned that Portland should not tax houses to subsidize cars. Another point for the gas tax. Finally, the economist urged Portland to fix existing streets and not spend money building shiny new projects. Gas tax, for the win.

If you are Big Oil, you hate the Portland gas tax

Everyone from community groups to neighborhood associations to the Portland Business Alliance supports the gas tax. Who is opposed? People who sell gasoline. The Oregon Fuels Association, which helped defeat a city gas tax in Pendleton in November, has raised nearly $400,000 to fight street improvements in Portland. About one-quarter of the money, including a check for $50,000 from the Western States Petroleum Association, came from out-of-state interests. I myself recently received a big glossy mailer, paid for by Big Oil, beseeching me to vote no on Measure 26-173. While it’s flattering that Big Oil has been paying so much attention to little old Oregon lately, perhaps we Portlanders can make our own decisions about improving our streets.

The temporary gas tax is a step in the right direction

To be clear, a temporary 10-cent gas tax won’t solve all of Portland’s street woes. But sixty-four million dollars over four years will let the city tackle the most urgent paving and safety projects. Perhaps, too, it will remind Portlanders why investing in city streets is well worth our tax dollars. As neighbors see potholes getting filled and intersections operating without injury, they might feel a sense of satisfaction that local taxes are improving local livability. Our streets, our safety, and our sustainability depend on investments like this.

[button link='{“url”:”http://www.sightline.org/2015/02/10/portlands-vision-zero-plans/”,”title”:”Like what you|apos;re reading? Here|apos;s how Portland is designing safer streets.”}’]

Comments are closed.