I want a political party that represents my views. Like many Oregonians, Washingtonians, and a growing number of Americans, I’m not a Democrat, and I’m not a Republican.

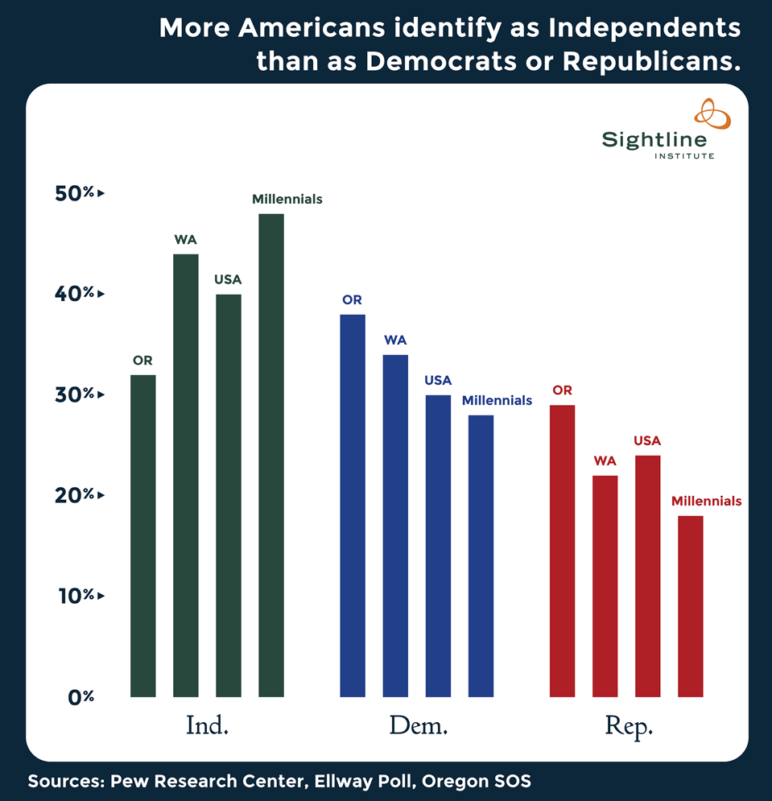

Independents—people who don’t identify with one of the two major parties—are the biggest and fastest-growing group of US voters. At last count, 40 percent of Americans considered themselves independent. The same is true in Cascadia: in Washington, an estimated 44 percent of registered voters identify as independent; in Oregon, one-third of registered voters are not registered Democrat or Republican. The trend is even more stark among younger Americans: nearly half of millennials consider themselves independent.

Yet Cascadians who live in the United States are continually shoe-horned into the two major parties because, like Richard Gere in An Officer and a Gentleman, we’ve got nowhere else to go.

More parties would better represent voters’ views

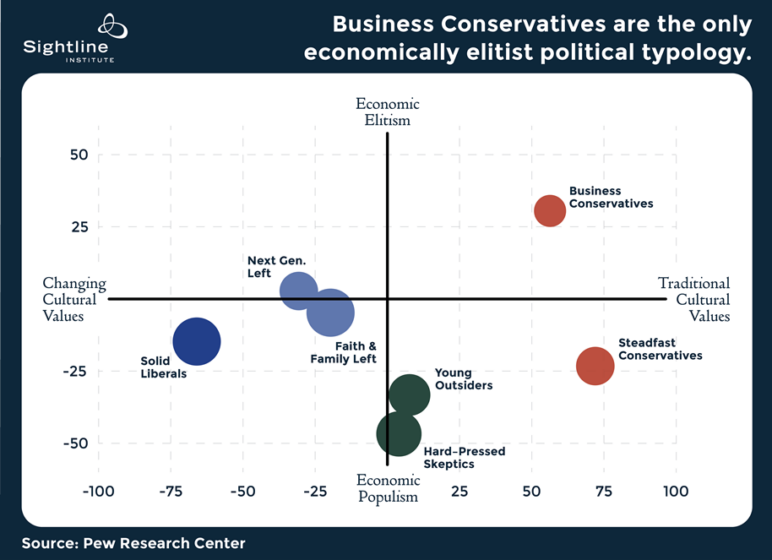

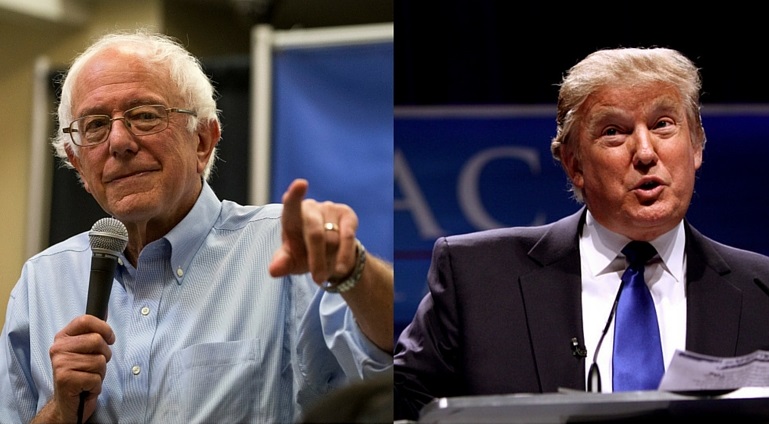

The growing number of Americans who don’t identify with either major party and the surprising popularity of party-outsiders Sanders and Trump indicate Americans want options outside the two major parties. Two parties can adequately represent people’s views along a single axis, but when views bifurcate along two different axes, two parties cannot reflect the diversity of political views. American voters span a spectrum from progressive to conservative on a left-right cultural axis, and they span a spectrum from elitist* to populist on an up-down economic axis.

Using data from the Pew Research Center’s 2014 Political Typology Report, I charted seven of Pew’s political typologies left to right—progressive to conservative—and top to bottom—economic elitist to economic populist. (See the Methodology section at the end of this article for details.)

This two-axis analysis suggested several points:

- Culturally conservative and economically elitist Americans, the “Business Conservatives” in the upper right quadrant, feel at home in the Republican party. However, business elites are worried that rising populist sentiments may hurt their bottom line, and the elitist GOP establishment is horrified that an uncouth populist like Trump is laying claim to its party banner.

- Culturally conservative and economically populist voters, the “Steadfast Conservatives” in the lower right quadrant, are relatively satisfied with the Republican party’s cultural conservatism but may feel alienated from the Republican party’s elitist economic policies. It follows that many of these voters are thrilled to hear Trump trumpet a culturally conservative worldview while also expressing populist economic messages, like limiting free trade and spending taxpayer dollars solving problems at home—not playing world police. Many Trump supporters also favor increasing taxes on the wealthy.

- Culturally moderate and economically populist voters, the “Young Outsiders” and the “Hard-Pressed Skeptics” in the lower middle quadrant, are dissatisfied with both parties, possibly because both parties are too focused on cultural issues rather than economic populism. Many of these voters are delighted to hear Sanders hammer on wealth inequality, financial access to college, a living wage, limiting free trade, and solving economic problems at home rather than paying to play world police.

- Culturally progressive and economically moderate Americans—“Faith and Family Left,” “Next Generation Left,” and “Solid Liberals” in lower left quadrant—feel pretty happy with the Democratic party. But the Democratic establishment is uncomfortable with Sanders’ strident populism.

For the parties to maintain control of their banners and for more voters to see candidates they can get excited about, the United States needs parties that represent more of this diversity of views.

Winner-take-all voting suppresses third parties

The United States’ archaic winner-take-all voting system allows the candidate with the most votes to win the whole election, even if he or she does not win a majority of the votes. Third-party candidates are almost always doomed to fail, either to become “spoilers” who hand the election to the less popular of the two major party candidates (Nader spoiled it for Gore, Perot spoiled it for Bush) or else to get weeded out in top-two primaries like Washington’s.

The popularity of party-outsiders Sanders and Trump shows voters are looking for views outside the two major parties’ orthodoxies.

Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump understand the constraints of the winner-take-all system. Sanders, an Independent-Socialist-Democrat, and Trump, an Independent-Democrat-unaffiliated-Republican, figured the odds of successfully infiltrating a major party’s primaries were higher than the odds of successfully running as third-party candidates. The popularity of party-outsiders Sanders and Trump shows voters are looking for views outside the two major parties’ orthodoxies. But when the voting system works against third parties, third-party candidates can’t win, third parties can’t grow, and voters who prefer third parties can’t vote their conscience without feeling like they are throwing away their votes.

Many Oregonians (including yours truly) are members of the Independent Party of Oregon: enough of us that the state awarded us major party status last year. But despite our numbers, winner-take-all voting prevents independents from winning elections in part because voters are afraid to spoil the election for their preferred Democrat or Republican candidate. Practicality propels us to keep voting for the Democrat or the Republican. Independent voters are barred from even voting in May’s closed presidential primaries unless we defect and register as Democrats or Republicans.

In most stable Western democracies, Sanders and Trump wouldn’t have to foist themselves on hostile parties; they could just run on their own parties’ platforms. Simple. Most Western democracies use a form of voting that enables three or four viable parties. Of the 34 OECD countries, only the United Kingdom and its former colonies Canada and the United States still use winner-take-all voting—an eighteenth-century system that enables two parties to disproportionately dominate elections. Almost all other prosperous democracies use some form of proportional representation—a twentieth-century voting systems that enable multiple parties to accurately represent voters’ views.

Yet even there, the wildly unrepresentative 2015 UK election results stirred calls for adopting a more modern voting system, and Canada has vowed that 2015 will be the last first-past-the-post election it ever holds. In 1996, New Zealand broke its eighteenth-century English winner-take-all voting bondage and adopted twentieth-century proportional representation voting, immediately adding several viable parties and making the legislature represent the full range of voters.

It is time for the United States to join the civilized world and shed its archaic voting system. The Cascadian parts of the country, especially Oregon and Washington, could lead the way, as I will detail in my next article.

[button link='{“url”:”http://www.sightline.org/2016/03/07/how-trump-is-winning-even-though-most-republicans-arent-voting-for-him/”,”title”:”Find out how trump is winning—even though most Republicans aren|apos;t voting for him.”}’]

Proportional representation voting enables multiple parties

Robert Reich envisions rising economic populism manifesting itself as a new “People’s Party.” While he is right that many people on both sides of the left-right divide are desperate for more economically populist candidates, he is, sadly, wrong that America will create a viable additional party just because lots of people really, really want one (or two).

If really wanting were enough, the United States would have created more viable parties during the Progressive Era. If wanting were enough, Ross Perot’s Reform Party would still be around. The paucity of parties stems not from a lack of interest but from a lack of a modern voting system. Until the United States updates how it votes, American voters will only have two viable options on their ballots, no matter how many people click their heels and wish it weren’t so.

By design, winner-take-all voting disproportionately advantages two major parties, while proportional representation voting empowers parties in proportion to how many voters their platforms actually represent.

The example of New Zealand

New Zealand used winner-take-all voting for most of the twentieth century, and two major parties, National (conservative) and Labor (progressive), consistently won almost all the seats. Since switching to proportional representation in 1996, the Green Party (progressive, environmental), the New Zealand First Party (centrist, populist, nationalist), and the Maori Party (representing indigenous people) have gained seats in Parliament proportional to the number of voters who support them (12 percent, 9 percent, and 2 percent, respectively).

The example of Canada

In Canada, thirteen commissions, assemblies, and reports over the years recommended proportional representation. But Canada continued to suffer disproportional elections: Stephen Harper and the Conservative Party ruled for nearly a decade even though only a plurality of voters (36 to 40 percent) voted for the Conservative Party. Conservatives formed a minority government with 36.3 percent of the votes in 2006, but won a majority 53.9 percent of the legislative seats in 2011 with just 39.6 percent of the votes.

In 2015, the Liberal Party and the progressive New Democratic Party (NDP) both campaigned on the promise to abolish first-past-the-post voting. The Liberal Party swept to power with 54.4 percent of the seats (but only 39.5 percent of the vote), while the NDP won 13 percent of the seats (with 19.7 percent of the vote). The Liberal Party favors instant runoff voting (IRV), likely because it might let Liberals continue to win close to a majority of seats. The NDP favors proportional representation (specifically, a form called Mixed Member Proportional).

Prime Minister Trudeau has promised to form a multi-party committee to explore the question of which voting system is best. The NDP recommended that, in keeping with the spirit of the exercise, committee membership should be proportional to the parties’ share of the vote in fall 2015: five Liberals, three Conservatives, two New Democrats, one Bloc Quebecois, and one Green.

The US opportunity

In the United States, hardly anyone even talks about the benefits of proportional representation. In 1967, the US Congress mandated single-member districts, foreclosing proportional representation at the federal level. Good news: there are no Constitutional barriers to repealing this law and replacing it with something like the Fair Representation Act. Bad news: passing such an act through Congress will be a hard slog. As with most important changes in the United States, national reform is a long road that starts with the states.

States can experiment and spread success. Oregon and Washington could implement proportional representation in state legislatures. As more states follow suit, a bevy of benefits would compound: more voters would gain experience electing representatives through proportional voting, viable parties would gain ground, Sanders and Trump supporters would grow accustomed to electing like-minded representatives at the state level, and Congress would feel the pressure to adopt, or at least allow, proportional voting at the national level. States could make the first inroads into reforming federal elections by creating an interstate compact for fair representation and taking it to Congress asking for permission.

[button link='{“url”:”http://www.sightline.org/2015/05/19/no-taxation-without-proportional-representation/”,”title”:”Want more? Kristin explains proportional representation with fruits and veggies.”}’ color=”orange”]

Proportional representation could also boost civic engagement, cripple gerrymandering, and end partisan gridlock

I am not constructing an elaborate ruse to bolster my pet political party. I am advocating to improve democracy in Cascadia so that Cascadians can make progress towards sustainability. Updating the US voting system to one that empowers more than two major parties would not only give me, other independents, and Sanders and Trump supporters a political home; it would convey copious other benefits.

As I have previously described in greater detail, winner-take-all voting yields negative campaigns that turn off voters. Because a candidate can win by gaining more support than the other guy, but not necessarily majority support, smearing an opponent, or even sullying the whole election process so that voters simply stay home on election day, can be a successful strategy. When voters have the option to more fully express their preferences because they can rank candidates or choose a party that more closely aligns with their views, candidates and parties are motivated to attract voters to their ideas, not to repel voters from their opponents or from participating in civic life at all.

Proportional representation voting encourages voters by ensuring that every vote counts.

In addition to encouraging negative campaigns, winner-take-all voting also discourages voters with disproportionate or unrepresentative election results. What’s the point in voting when you can never actually elect someone who represents your views? Voters who prefer third-party candidates, conservative voters who live in urban areas, and progressive voters who live in rural areas face this disheartening situation every election: if you don’t agree with the plurality of voters in your district then your vote doesn’t matter. Proportional representation voting encourages voters by ensuring that every vote counts. Conservatives, progressives, and third-party enthusiasts can all elect legislators in proportion to their strength at the ballot box.

A winner-take-all system also fuels the gerrymandering blight that plagues the United States. Gerrymandering can only exist when single-winner districts lines can be drawn around a particular demographic of voters. With proportional representation, it doesn’t matter who draws the district lines, because districts are multi-winner or are balanced by a regional or statewide vote that ensures proportional results no matter how or by whom the districts are drawn.

Winner-take-all voting and the resulting two dominant parties also jam the system with partisan gridlock. The two-party system often rewards legislators for being obstructionist and punishes them for forming inter-party alliances to get things done. With more parties, obstructionists would become irrelevant to the art of governing, which would be carried out by skilled deal-makers. For example, imagine the United States added two additional parties—a conservative populist party that would occupy the political space around where the “Steadfast Republicans” are located in the graph above, and a moderate-progressive populist party near the “Hard-Pressed Skeptics” and “Young Outsiders.” A single party could no longer shut down public functions by taking its toys and going home. The other three parties would work out solutions and ignore the obstructionists. The two populist parties and the Democrats might come together to bolster Social Security and install Universal Health Care. Or they might draw enough support from the Democrats and Republicans to ensure trade agreements include protections for the American middle class.

The question of governmental effectiveness

Conventional wisdom in the United States says that, while a multi-party system might be more representative of the people, additional accuracy comes at the cost of governmental effectiveness. In a two-party system, the thinking goes, the party in charge can get things done, but in a multi-party system the small factions would be constantly fighting and never accomplish anything. If Congress is gridlocked now with two parties, just imagine what it would be like with three or four!

Researcher Arend Lijphart conducted an exhaustive international study and found that multi-party systems are more effective at governing, maintaining rule of law, controlling corruption, reducing violence, and managing the economy—particularly minimizing inflation and unemployment while managing the economic pressures arising from economic globalization. His conclusion boils down to: good management requires a steady hand more than a strong hand. Two-party systems provide more of the latter with a strong, decisive, government, while more representative multi-party democracies provide more of the former with steady governance.

The party in charge in a two-party system can make decisions faster, but once the other party gains control it often abruptly reverses course, throwing things into disarray. And the ruling party often has a hard time implementing decisions that they made over the vehement objections of important sectors of society, since those sectors continue to oppose the outcome at every turn. A multi-party government may take longer to form the consensus needed to make a decision, but once made, decisions are durable, implementable, and not at constant risk of being overturned.

Conclusion

A representative democracy means voters elect representatives who share their values, beliefs, and priorities. With more than one set of issues at stake, two political parties cannot possibly field candidates who reflect the different permutations of voters. The growing number of independent voters and the Sanders and Trump insurgencies demonstrate voters’ discontent with the deficient representation that two major parties can offer. So while outsiders like Sanders and Trump may never win a single-winner seat like the presidency, with proportional voting, the many voters rallying to the Sanders and Trump flags could elect legislators in proportion to their numbers.

Next time, I’ll tell you how Oregon and Washington could take the hint and forge a path towards adopting modern voting systems that facilitate more representative democracies.

*I use the term “elitist” for lack of a better term: it represents a preference for policies that benefit the economic elite, including corporations, financial institutions, and the wealthy. Economic elitists tend to oppose policies that distribute economic benefits to working- or middle-class people, like Social Security, taxes on wealth or capital gains, limits on “free trade” to protect domestic blue-collar jobs at the expense of corporate profit, and prioritizing domestic spending that may benefit Americans broadly over international interventions that may benefit corporations.

Methodology for Two-Axis Graph

For nearly three decades, the Pew Research Center, a nonpartisan research center, has conducted research to understand the nuances of Americans’ political ideologies. The latest iteration of its research efforts, based on a large survey and follow-up interviews conducted in 2014, identified eight political typologies, seven of which are at least somewhat politically engaged. (“Bystanders,” the eighth typology, aren’t registered to vote and don’t follow politics.)

Defining the left-right axis

The left and right split on the question: should we welcome cultural changes, or should we honor traditional or historical values? (An informal litmus test: if you think it is super-cool that the new “Star Wars” protagonists are a woman and a black man, you are probably culturally progressive; if you feel uncomfortable with the change in casting, you are likely culturally conservative.)

Other research confirms the change-v-tradition divide closely tracks the left-right, Democrat-Republican, and urban-rural divide. Most progressives choose to live in dense, ethnically diverse cities where they are exposed to cultural differences; most conservatives choose to live in rural areas or small towns where most neighbors stick to traditional lifestyles.

To calculate each typology’s left-right placement, I used three Pew survey questions that seemed to address the change-v-tradition divide. Respondents chose one of the two options in each question below.

- In your view, has this country been successful more because of its ability to change OR more because of its reliance on long-standing principles?

- Should the U.S. Supreme Court base its rulings on its understanding of what the U.S. Constitution meant as it was originally written, OR should the court base its rulings on its understanding of what the U.S. Constitution means in current times?

- What do you think is more important – to protect the right of Americans to own guns, OR to control gun ownership?

I subtracted each typology’s average agreement with the welcome cultural change type option from the average agreement with the honor traditional values type option and found the average. Higher numbers placed that group further to the right, and more negative numbers place them further to the left.

The three Democratic-affiliated typologies (Solid Liberals, Faith & Family Left, Next Generation Left) all welcome cultural changes, saying that the United States has been successful because of its ability to change, that judges should interpret the US Constitution as appropriate for current times, and that it is important to control gun ownership. The two Republican-affiliated typologies (Business Conservatives and Steadfast Conservatives) both honor traditional or historical cultural values, agreeing with the statements that US success is due to reliance on long-standing principles, that judges should interpret the Constitution as originally written, and that it is important to protect the right to bear arms. The two moderate or culturally ambivalent groups (Hard-Pressed Skeptics and Young Outsiders) are mostly evenly split on these questions.

Note: Left and right often correlate with religious views, but not always. For example, Faith & Family Left are religious Democrats who oppose same-sex marriage and don’t believe in evolution. Affluent, educated Business Conservatives are staunch Republicans who believe in evolution and have mixed views on same-sex marriage. Young Outsiders lean Republican but support same-sex marriage and abortions and believe in evolution. Democratic-leaning Hard-Pressed Skeptics are slightly opposed to same-sex marriage and lean towards making abortions illegal.

Defining the up-down axis

To separate economic elitism from economic populism, I used four of Pew’s questions that addressed whether the government and the economy should cater to the interests of economic elites such as the wealthy and corporations, or spread wealth widely, protect domestic jobs, and solve domestic economic problems. Unfortunately, Pew did not ask respondents about wealth inequality or tax reform, so I used these four Pew questions:

- Which comes closer to your view: The economic system in this country unfairly favors powerful interests OR The economic system in this country is generally fair to most Americans?

- Thinking about the long term future of Social Security, do you think some reductions in benefits for future retirees need to be considered OR Social Security benefits should not be reduced in any way?

- Which comes closer to your view: It’s best for the future of our country to be active in world affairs OR We should pay less attention to problems overseas and concentrate on problems here at home?

- In general, do you think that free trade agreements between the U.S. and other countries have been a good thing OR a bad thing for the United States?

As above, I subtracted each group’s level of agreement with the more populist position from their level of agreement with the more elitist opinion and took the average. Higher numbers placed the group higher up, and negative numbers placed them lower.

The 10 percent of Americans Pew identifies as “Business Conservatives” are probably most closely aligned with GOP economic views but stand almost alone among Americans on economic issues. Business Conservatives believe the economic system is generally fair to most Americans; every other group believes the economic system unfairly favors powerful interests. Business Conservatives believe the US should consider cuts to Social Security benefits; every other group agrees that Social Security benefits should not be reduced in any way; solidly Republican Steadfast Conservatives support Social Security every bit as much as Solid Liberals, and Republican-leaning “Young Outsiders” support it even more vehemently than Solid Liberals. Business Conservatives strongly believe the US should be active in world affairs, whereas Hard-Pressed Skeptics and Young Outsiders fervently believe, and Steadfast Conservatives strongly believe, the US should concentrate on solving problems at home. Business Conservatives are also at odds with Steadfast Conservatives on free trade: the former support free trade, and the latter oppose.

Note: Immigration is often cast as a cultural issue (opposition to cultural changes that immigrants bring), but it also has an economic dimension. More competition can drive down wages, so the US Chamber of Commerce supports immigration reform while blue-collar Americans often it. Put the two together and it is no surprise that culturally conservative and economically populist Steadfast Conservatives are more likely to oppose illegal immigration than any other group.

Comments are closed.