Images can be powerful tools for connecting climate change to people, to strike an emotional chord, and to broaden the range of audiences who might start paying more attention.

Cue the polar bears? Think again!

Are polar bears & glaciers still your go-to #climatechange images? Pro tip: they shouldn’t be.

Polar bears have become a handy visual signal for a climate change story, but this shorthand doesn’t cut it when it comes to gripping people and motivating action. Neither do penguins, glaciers, icebergs—that whole clutch of iconic climate imagery. Ditto: shots of rallies and protesters. They’re easily ignored. Worse: they can prompt cynicism or trigger problematic climate frames (far away, impersonal, overwhelming, “not my kind of people”) rather than connecting with the values and priorities of a wide range of audiences.

So why do these same old images still crop up all over the place? One problem is simply that better options aren’t obvious or easy to find.

Until now, that is. Climate Visuals—a project of Climate Outreach (formerly COIN), in collaboration with the Global Call for Climate Action, the University of Massachusetts, 10:10, and the Minor Foundation—has developed guidelines for better climate imagery based on extensive testing involving thousands of people in the UK, US, and Germany in 2015. They’ve also launched a first-of-its-kind, interactive, evidence-based online image library (I know! Exciting, right?).

The research is solid. The seven principles are good ones to follow, but, to be honest, I see the real value of this resource in the detailed notes you’ll find accompanying each photo, explaining why it’s powerful and the responses it’s likely to draw. In fact, browsing the library is a learning experience at every turn; you can even search for the type of response you’re after—for instance, images that evoke positive emotions or are likely to be shared or encourage demand for change.

Here are MY TOP TAKEAWAYS:

Skip photos of polar bears and protesters, and find photos that tell new climate stories.

Feature real people and human stories.

Not staged photo ops or stock photos, but shots of people that tell a real, human story. Close ups and “eye-contact” = good. Photos of children = really good, and more likely to be shared. Photos of politicians = not so good.

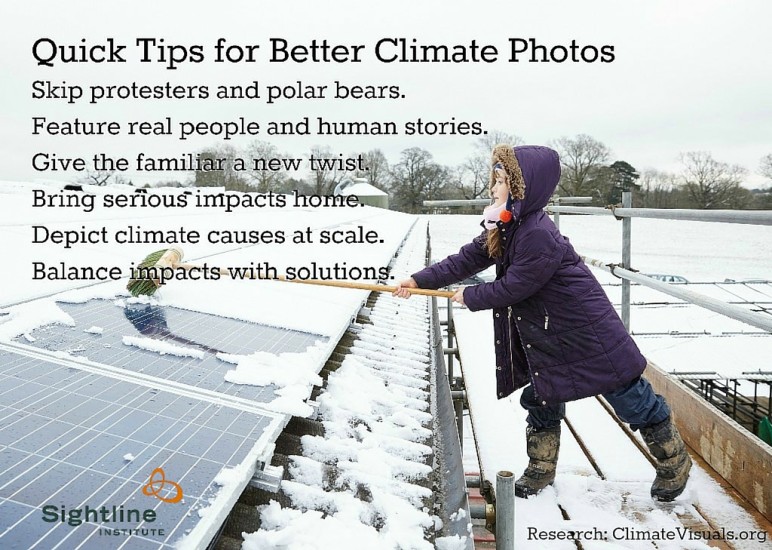

Surprise and contrast (and subvert) to give the familiar a new twist.

Photos that combine something easy to understand with something extraordinary—visually extreme or out of whack or even funny—grab attention and connect on an emotional level. For example, instead of a canned photo of solar panels, show a surprising new solar energy story: a child in the routine act of sweeping snow off her family’s panels. Or, the bleak yet heartwarming contrast of a young couple’s wedding day shot against the backdrop of devastating flood damage.

Bring serious impacts closer to home.

Images showing climate impacts should tell a human story. Show faces and places—and situations—that your audience will readily relate to (recognizable and local scenes, common family activities, people working together or helping one another).

Show causes at the community or industrial scale.

Photos that single out an individual in her car to illustrate climate causes can trigger defensiveness rather than engagement. It’s far better to show traffic congestion, illustrating a shared carbon pollution problem—and one that just about everybody loves to hate. Photos of the collective and industrial-scale causes of carbon pollution motivate demand for community solutions. Also emotionally compelling are photos that depict the shocking scale of fossil fuel operations, damage, and accidents.

Show a way forward. Balance imagery of impacts and causes with photos of positive, practical solutions.

Balance climate impacts and causes with photos showing solutions, especially regular people putting everyday solutions to work—and being better off for it. (Again: skip the staged celebrations of clean energy and efficiency measures. People don’t buy a contrived scene; they know authentic when they see it.) The emotional response to damage and human suffering is strong, but these images on their own can leave people feeling powerless to act. Another photo or accompanying text should offer a constructive response. Solutions spark positive emotions across the political spectrum and can help motivate action and rewrite social norms toward low-carbon behaviors and attitudes.

Journalists, campaigners, bloggers, and anyone else telling climate stories: chances are you’ll find your next climate photo (and learn a lot about what is visually compelling) at climatevisuals.org. No single photo can do it all, but this is a good reminder that the imagery associated with climate change can do a better job opening minds and emotionally engaging more people. Here’s our printable, shareable cheat sheet on Climate Visuals’ most practical takeaways:

Comments are closed.