Tacoma may soon be home to the Northwest’s next liquefied natural gas (#LNG) facility.

Tacoma may soon be home to the Northwest’s next liquefied natural gas (LNG) facility, with a $275 million plant positioned to move forward after the City of Tacoma published the project’s Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) in October 2015. Most observers have treated the project as a done deal, but the FEIS contains some alarming oversights. Specifically, it fails to specify the demand the facility will place on the region’s resources, and it creates a loophole through which project backer Puget Sound Energy might greatly expand the scope of the project without further review.

A so-called “peak-shaving facility”

Regulators and Puget Sound Energy (PSE) call the proposed plant a “peak-shaving facility,” but the label is only partially correct. Peak-shaving facilities receive natural gas by pipeline, cryogenically refrigerate the gas until it becomes a liquid, and then store it for high-demand periods like cold winter days. Converting natural gas into a liquid dramatically shrinks its volume, allowing larger amounts of gas to be stored or transported at once. When customer demand increases to its maximum range, a peak-shaving facility converts the liquid back into a gas and distributes the gas to customers through a utility company’s pipeline network. There are about 60 peak-shaving facilities in the US.

Peak-shaving facilities are typically small plants that do not operate continuously throughout the year. ECONorthwest’s Economic Impact Analysis estimates that the Tacoma facility will produce 87 million gallons of LNG per year. Plants of this size that operate every day for 24 hours per day and supply independent buyers are not considered true peak-shavers but don’t have their own distinct name.

PSE expects utility customer demand to increase over the next 20 years, and the peak-shaving capacity of this project would meet 50 percent of that predicted need. Yet the project’s proposal doesn’t stop there, and the facility would have two other noteworthy primary purposes: 1) to serve as a fueling station for ships that run on natural gas and 2) to sell LNG to “other industry merchants.”

[button link='{“url”:”http://www.sightline.org/tag/natural-gas/”,”title”:”Find out about other natural gas plans in the Northwest here.”}’ color=”orange”]

Supplying LNG-fueled ships

One main role of the Tacoma facility would be supplying LNG to marine vessels that run on natural gas. In 2015, the International Maritime Organization began implementing new emission standards to reduce diesel engine air pollution from the maritime industry, and LNG is one of the leading potential solutions for bringing ships into compliance. Ships that run on LNG emit about 25 percent less carbon dioxide than those that run on diesel.

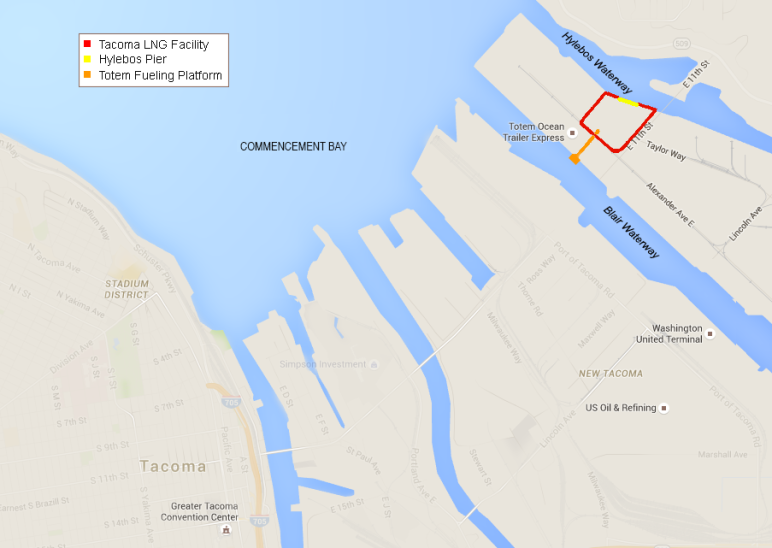

PSE has partnered with cargo transport company Totem Ocean Trailer Express to provide LNG for two cargo ships on Totem’s Alaska trade route. Totem is converting the ships from diesel propulsion to dual-fuel propulsion, which will allow the engines to run on either LNG or diesel. The Tacoma LNG facility would deliver LNG to Totem through a loading platform on the Blair Waterway.

On the opposite side of the facility, PSE would construct a pier on the Hylebos Waterway to receive bunkering barges and their tugboats from third parties. A bunkering barge functions like a floating gas station that delivers fuel to ships. Bunkering barges would load LNG at the pier and then meet vessels near Commencement Bay.

Selling LNG to “other industry merchants”

Separate from the refueling is the third component of the project, in which PSE would sell LNG to “other industry merchants.” Barges delivering LNG to those merchants might fill up at either the Hylebos pier or Totem’s loading platform on the Blair Waterway. (The proposal actually contradicts itself on this point: Section 2.2.1.1 indicates that the barges of other industry merchants “could be filled at either” platform, while Section 3.10.4.1 says there are no proposed barge trips to the Totem platform besides Totem’s trips.)

While the proposal estimates how often tanker trucks would be transporting LNG from the facility, it’s entirely unclear how many, how often, and what type of third-party ships would visit one or both piers. The FEIS merely notes that the port of Tacoma “has extensive capacity for existing and future water traffic” and that the proposal’s new ship traffic “would be minor in comparison to existing maritime traffic on the two waterways” (Section 3.10.4).

This oversight makes it impossible to estimate how other marine traffic, the environment, or the health and safety of the city’s residents might be affected. Where the numbers aren’t completely omitted, the estimates only include Totem’s two round trips per week, failing entirely to account for the other ships that will visit the docks. This underrepresentation of marine traffic numbers occurs in the analysis of maritime traffic impacts (See 3.10.3.10), impacts to recreational resources (See 3.7.4.2), and potential impacts to marine life (See 3.4.4.2).

The Tacoma facility would be one of the first marine bunkering facilities in the US, which might make it more difficult to pinpoint how much traffic to expect. Yet since it’s not the very first facility of this type, an estimate is not out of the question. A 2015 report by the American Bureau of Shipping indicates that there are nine other marine bunkering projects currently in development, not to mention established facilities in other regions. Not only is there data available from which to estimate the true marine traffic impacts of this project, but it’s irresponsible to approve a proposal that does not do so, and it sets a concerning precedent for other hybrid LNG facilities.

The problem doesn’t stop there. In fact, the facility could become an export project in all but name. PSE plans to use the Tacoma facility to load barges and trucks with LNG destined for “other regional markets seeking a cleaner fuel source.” Yet the document fails to specify what constitutes a regional market, potentially allowing the definition to expand in unforeseen ways. It’s possible, for example, that an LNG exporter in need of additional supply could be one of the buyers in the regional market, and this type of transactional relationship might present challenges. This possibility is not merely hypothetical: the proposed export facility Oregon LNG—which is not linked to the Tacoma LNG facility—would be capable of producing up to 9 million tons of LNG per year but applied for a permit to export 9.6 million tons per year.

Why does PSE want to build this facility?

The Tacoma facility will help PSE solve some problems with its natural gas supply chain. The company had previously leased LNG storage capacity at Williams Northwest Pipeline’s LNG plant in Plymouth, Washington, near the Tri-Cities, but Plymouth LNG shut down after an explosion at the facility injured five workers and forced an evacuation of 400 residents. Plymouth LNG is currently operating at half capacity and will be not be fully operational again until this April.

A second concern for PSE is actually other LNG project proposals. The Power and Natural Gas Task Force—an industry group, of which PSE is a member—expressed concern in its July 2015 report that high demand from LNG export terminals and methanol refineries could affect the gas supply of utility companies, especially on peak demand days. PSE also expressed these concerns in its 2013 resource plan. The utility anticipates increased customer demand over the next two decades, and the Tacoma LNG facility would help PSE control its future gas supply. The facility would connect directly to gas supply pipelines through two new pipeline segments that will run through Tacoma, Fife, and unincorporated Pierce County.

The Tacoma facility will also pave the way for expansion. A 2012 presentation by PSE indicates that the Tacoma facility would supply LNG to the utility’s Gig Harbor satellite facility and to a future satellite facility serving PSE’s Kittitas system. (A satellite facility stores LNG and can inject natural gas into pipelines when needed. It differs from a peak-shaver because LNG isn’t made onsite.) Puget Sound Energy has been pursuing expansion projects in Kittitas County for a number of years.

Where does the project stand now?

The Port of Tacoma approved a property lease for the facility in August 2014, and PSE hopes the project will be operational in 2018 after a three-year construction period.

A December 2015 lawsuit from the nearby Puyallup Tribe has also called into question whether the environmental analysis was adequate. The Tribe has challenged conclusions in the FEIS about water contamination that may result from construction at the proposed site, which is a Superfund site still undergoing cleanup for hazardous substances released by Occidental Chemical and other companies.

A poor precedent

Liquid natural gas is expected to fuel future diesel-to-LNG conversions for marine vessels and trucks. One of the impediments to switching from diesel to natural gas has been the lack of a fueling network, and the Tacoma facility can certainly help customers like Totem transition by helping make the switch to LNG more feasible.

What’s concerning is that no additional review of the project’s impacts would be required for future developments deemed to be within the scope of the proposal when the proposal lacks clarity on what is and is not within its scope. These oversights could set a precedent of failure to safeguard communities in the Pacific Northwest, which have seen a dramatic increase in fossil fuel shipping proposals including LNG, xylene, methanol, and coal export terminals, in addition to a staggering increase in shipments of oil-by-rail to port communities. If we give this project carte blanche for unlimited marine traffic, then what will we give the next one?

[button link='{“url”:”http://www.sightline.org/2015/07/08/tacomas-ticking-time-bomb/”,”title”:”Learn how oil trains are also putting Tacoma|apos;s residents at risk.”}’ color=”green”]

Comments are closed.