We don’t need to know the science of climate change inside and out in order to care or want to act to fix the problem. Non-scientists count on the experts to get the details right. But having a handle on the basics can be a game changer. Why? Gaps in our understanding about the mechanisms of climate change along with the metaphors we use to explain and visualize the problem dictate which solutions seem logical. Here’s an illustration:

Say you think of carbon dioxide as the natural and necessary stuff we breathe out and that plants take in. It’s part of nature. You can’t imagine how natural stuff could ever be bad enough to seriously damage the climate. And say you also aren’t clear how climate change is happening; you remember “something about a hole in the ozone letting too much heat in…” You want to do the right thing for the climate, so you recycle and turn down the thermostat and do your part to keep pollution out of the water.

If that’s your starting point, then it might not seem obvious to you that an economy-wide effort to cut fossil fuel emissions and shift to clean energy sources is the best way to tackle climate change. Indeed, getting you to buy in to appropriate actions may be a heavy lift.

The bad news is that this is a common starting place. FrameWorks Institute research on climate change and oceans, conducted on behalf of the National Network for Ocean and Climate Change Interpretation (NNOCCI) and supported by the National Science Foundation, revealed that most people don’t really have a good grasp of the basics. In fact, the most common default patterns of thinking—correct and incorrect—and the most prevalent information gaps about the problem are leading people astray.

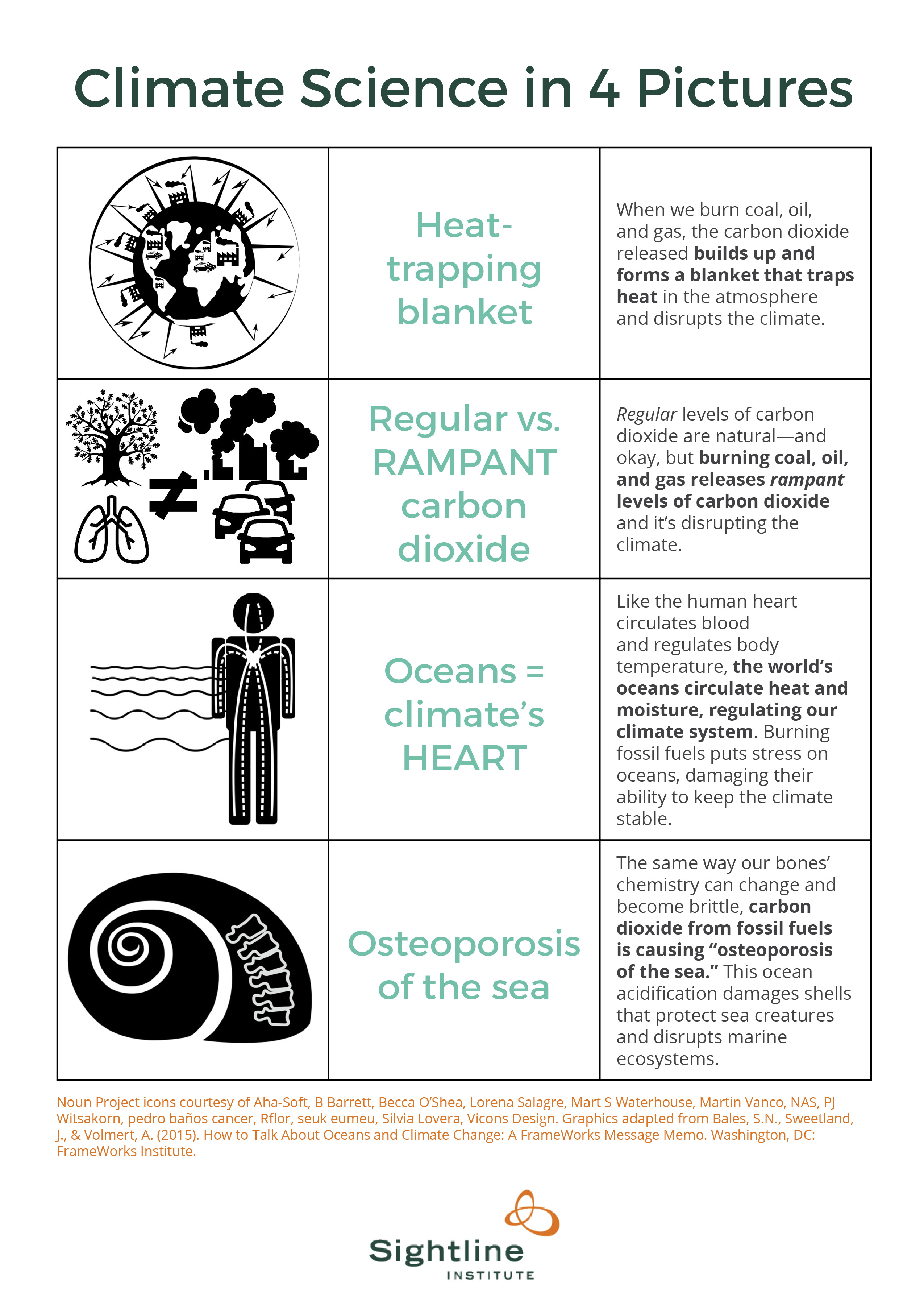

The good news is that FrameWorks has done extensive messaging research in the US and Canada to develop simple, memorable explanations of climate science basics that get people thinking in productive ways about causes and solutions. You can boil these down to four explanatory metaphors, simple, familiar visual comparisons that quickly explain abstract scientific concepts. Testing show that these particular “mental pictures” did help people see the links from causes all the way to solutions.

These explanatory metaphors an important part of consistent and compelling climate change narratives, answering a key question: What are the mechanisms at play here—and what’s going wrong? Our messages should address two other questions as well: Why does this issue matter to us at all? What should we do to move forward? We do this by connecting the issue to shared values and emphasizing solutions.

(Stay tuned for more on FrameWorks’ tested values messages and the most damaging communications traps to avoid).

Want more? Watch the art of talking climate science in less than 3 minutes.

Quick, simple ways to say how climate change works

Most people misunderstand the central mechanism of climate change. Unfortunately, “greenhouse gases” is not a visual explanation people readily understand or are likely to repeat. Testing showed that climate change is too often confused or conflated with the ozone hole, toxic and solid waste pollution, littering, and other unrelated environmental problems. And while most North Americans see human activity as a cause of climate change, too great a share don’t have a clear understanding of just what activities we are actually talking about or how exactly those activities impact the climate. It’s important to consistently link the cause—burning fossil fuels—to our explanations of the science.

On top of that, people don’t understand the role of carbon dioxide in climate change in the first place. They confuse it with carbon monoxide or assume that because carbon dioxide is a natural part of the life cycle, not an “unnatural pollutant,” it must be essentially harmless. With this perspective, it is difficult to fathom how it could cause all this damage.

You can see why plans to reduce fossil fuel use may not necessarily seem like the best answer.

That’s our cue to redirect. FrameWorks offers two rigorously tested ways of explaining these basics in just a few words, and in two visual metaphors. First, instead of the greenhouse metaphor, it’s more helpful to explain that burning fossil fuels forms a heat-trapping blanket in our atmosphere. Consistently starting with fossil fuels as the source and explaining how it keeps heat from escaping helps people understand the causes of climate change and more clearly see cutting emissions as a logical solution.

The oceans function as the #climate’s heart, keeping the system balanced and healthy.

Second, talking about regular vs. rampant carbon dioxide met people where they were, thinking that carbon dioxide is natural, and helped show them how burning fossil fuels is making for excessive amounts and throwing the natural balance out of whack.

These two metaphors, used together, helped people see that too much pollution from fossil fuels is the cause and helped shift thinking about solutions from the default individualist orientation—focusing on personal steps like recycling, hybrid cars, and turning off the lights—to system-wide, community solutions.

Next up: Most Americans simply haven’t heard of ocean acidification. When they do hear about it, they default to thinking about acid rain or dumping solid and toxic pollution into the water. In turn, they are likely to suggest fixes like banning chemical dumping, not necessarily cutting fossil fuel use or using clean energy like wind and solar.

But FrameWorks’ explanatory metaphor—osteoporosis of the sea—helped people to understand what acidification is and to draw reasonable conclusions about how to address it. In fact, explaining ocean acidification in simple, familiar terms that relate to people’s understanding of their own bodies, proved one of the most powerful ways to boost the sense of urgency for climate change solutions and to make the case to limit the use of fossil fuels.

Finally, when people think of climate change, they tend to focus only on warming. They don’t think of the climate as a system where land, sea, and atmosphere are connected and in delicate balance. In turn, they’re confused by climate impacts that don’t on their face appear to involve higher temperatures. That’s why it is difficult to see how climate affects weather, especially cold snaps, floods, or storms. FrameWorks found it helpful to compare the role of the ocean in regulating the climate system to the way our hearts function to keep our bodies healthy and regulate our temperature and circulation. The earth’s oceans function as the climate’s heart, keeping the system balanced and healthy. Just like a human body, when the heart is not performing well, the rest of the system is thrown off. This is a helpful starting place for explaining all kinds of strange and severe weather.

Here is your cheat sheet for deploying these simple and effective climate science “pictures” in your work.

Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our free use policy.

More climate change messaging tips here.

Methodology: FrameWorks’ Strategic Frame Analysis is a combination of qualitative, quantitative, and experimental testing. This particular research project draws on insights from over 18,000 people over many years.

Bales, S.N., Sweetland, J., & Volmert, A. (2015). How to Talk About Oceans and Climate Change: A FrameWorks Message Memo. Washington, DC: FrameWorks Institute.

russ

It is right for us to think postively about the new Paris Accord as it presents the horror, the hallelujah, and the path to hope. The accord is promising to place an enormous bet of trillions of dollars per year in the not so distant future, 5 years or so. Their “bet” is that technological and societal solutions will make a big dent in the CO2 that is menacing the world. But they more importantly are seen to be hedging their tech bet and banking on Mother Nature to do the heavy lifting in managing our CO2 abuse. If we help her by restoring and enhancing the amount of plant life on this blue planet. I’ve been calling to restore the trees and seas for decades and it’s good to see this prominently and firmly placed in the Paris Accord as vital to saving the world as we know it. The fact remains that on this planet there is but 9% of it capable of sustaining trees, and most of that is already forested. The oceans and thier ocean pastures which are presently in a terrible depleted condition offer 70% of this blue planet where if we help Mother Nature she will help us. http://russgeorge.net/2015/12/16/co2-clear-and-present-danger-is-first-to-oceans-not-climate/

Lee James

This is helpful, thank you.

No question about it … we see lots of ways to talk about climate and CO2. A favorite for those close to the fossil fuel industry is to talk about CO2 as food. We’re putting food into the air — as if doubling the level of food in the air is part of our adaptation. Even plants might object, as they experience too much of a good thing.

Dave McArthur

Please do not confuse my cryptic comments with rudeness and arrogance.

The human ego is capable of ingenious, incredible trickery, self-deceit and general denial of change/stewardship. The ego can easily make us our own worst enemy and generate rationales justifying our unsustainable actions. This is always reflected in some way in our language. Such is the human condition. It is a situation best understood and transcended with compassion. Could it be the author and members of the Frameworks Institute do not understand the paradox of communication and/or lead unsustainable lives? This question is prompted by these sample questions:

Who are the “non-scientists” you speak of? Could such a notion denigrate and dismiss the innate intelligence of all human beings and alienate your audience? What is science?

What is “climate change”? Is it good or bad? Why do you conflate climate change with types of climate change such as solar-induced, tectonic induced, human induced etc?

What is an economy? Are you confusing an economy with a diseconomy, which is what we have?

Why do you symbolize fossilized biomass as “fossil fuels”? Why do you believe they exist for us to burn?

Is warming good or bad? Why do you speak of warming rather than warming-up? Are you conflating these two vastly different processes? Surely such conflation denies the essential thermodynamics of the universe and the finite nature of all things?

Why do you speak of “greenhouse gases” rather than, say, “Warmer Trace Gases”? Why do you evoke images of Earth’s atmosphere as a greenhouse? What is our essential experience of a greenhouse? What is the history of this evocation?

Why do you evoke images of Earth’s atmosphere as a “blanket”? Are not blankets designed to suppress air convection? How does the evocation of Earth’s atmosphere as a blanket impact on teaching (a) the powerful convective nature of air, (b) the relatively poor conductive capacity of air and (c) intelligent design of insulation systems?

This very well-meaning article prompts these and much deeper questions of how we can transcend the limitations of thought, paradox and the ego in general. Could it be fine-intentions are insufficient, knowledge is not necessarily wisdom and we can say one thing and do the opposite with ease? Does our global malaise reside in our use of the English language? Much more at http://truehope.info/wordpress/quick-a-z-wise-word-use-guide

Benoit St-Jean

I particularly like the osteoporosis image !

But, being a profesionnal in climate change, I would not know how to use this «regular vs rampant carbon dioxide» to explain the overproduction of CO2. Maybe it’s a language or cultural question (English not my language and I’m American but not US American)…

Merci ! for these useful tools

Benoit (@GoEcoSynergies)

Anna Fahey

Thanks, Benoit. (Bonjour!?)

I think that the point is to acknowledge that people see C02 as something natural (meet them where they are vis a vis “regular” amounts) and then stress that what we have now is not regular but rampant–too much, out of control, excessive, unnatural, abnormal, overload…etc. But my understanding of the research is that it’s the comparison that counts (and the word rampant, in particular, worked for Americans).

Benoit

Merci ! for the explanation

Now its clear : )

«Rampant» would not have the same meaning in French

John Blumthal

The verbal and visual images you provide are useful. One, however, struck my eye discordantly. A few years ago I heard David Suzuki speak, and he provided an image of the earth’s atmosphere which changed my perception forever. If you envision the earth as the size of a basketball, he said, the atmosphere is a single layer of plastic cling-wrap applied to the basketball. This was so hard for me to believe that I went home, looked up the dimensions of the earth, the atmosphere, a basketball and the thickness of cling-wrap and verified his metaphor for myself. The image you provide with the “heat-trapping blanket” reinforces what is probably a common misperception of the volume of the atmosphere. The atmosphere is an incredibly thin film on the surface of our planet, and understanding this makes it much easier to envision how it can be impacted by human action.

Anna Fahey

I really love the basketball and cling-wrap image. Thank you. I’m going to use it.