A few weeks back, a reporter caught an unnamed coal industry executive in a stunning admission: environmental opposition to coal terminals has been a huge boon for the coal industry.

“I believe these agencies and environmental groups are doing the coal producers a favor by not approving or supporting the approval of these terminals…If the terminals were already built and in operation, few, if any, would be exporting coal as current pricing wouldn’t support it.” [Emphasis added.]

Given last week’s stunning news that Cloud Peak would suspend its coal export commitments from 2016 through 2018, this assessment might seem spot on. Yet if anything, the industry insider underestimated how dire coal industry’s finances would have been if Northwest ports had moved forward.

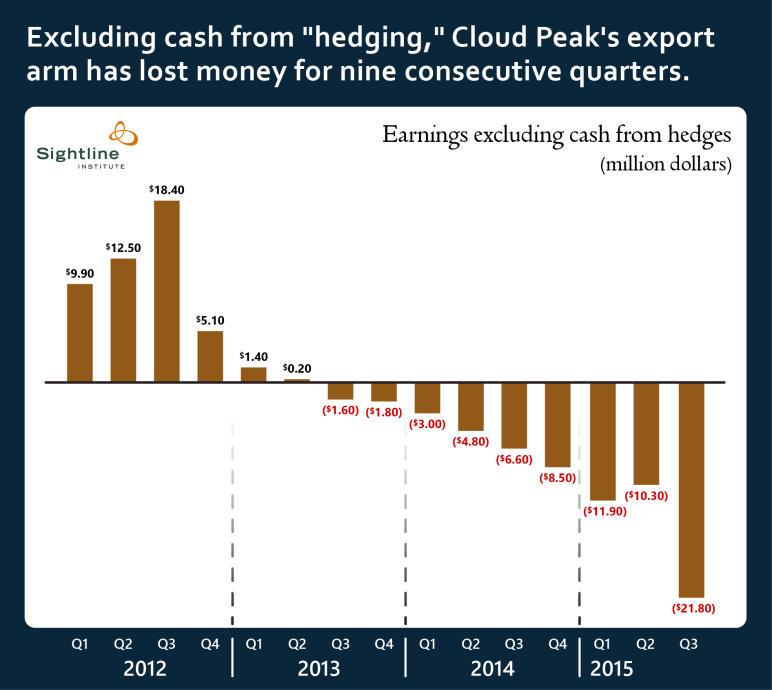

For proof, look no further than the third quarter financial results of Cloud Peak Energy, the only company to ship significant volumes of Powder River Basin (PRB) coal to Asia over the past several years. Excluding futures market transactions, Cloud Peak’s export arm lost nearly $22 million from July through September 2015, the company’s ninth consecutive quarter of export losses:

Cloud Peak’s export earnings, 2012-2015, by Sightline Institute, available under our free use policy.

Astonishingly, Cloud Peak lost all that money while moving a piddling 900,000 tons of coal overseas. (Yes, in the coal world, 900,000 tons is a piddling amount.) The specifics of those losses are somewhat complicated; not only did Cloud Peak lose money on actual sales, the company also paid steep penalties for not shipping enough coal. Still, Cloud Peak was losing between $10 and $15 on every ton of coal it shipped to Asian customers during the quarter.

Notably, Cloud Peak has far and away the best export economics of any PRB coal company. Peabody and Arch, the other two major players in the PRB export game, would have lost even more than Cloud Peak if they had tried to export their wares to the Pacific Rim.

So just imagine the dire straits the coal industry would have put themselves in had Northwest coal ports moved forward as quickly as their proponents had hoped. Right about now, the first phases of several massive projects would be nearing completion, with the capacity to ship roughly 50 million tons of coal to Asia each year. To finance construction, the ports likely would have locked coal companies into long-term export contracts saddling them with losses of $10 to $20 per ton on roughly 12.5 million tons of coal per quarter.

By slowing down and blocking coal terminals, the environmental community may have saved PRB coal miners some $700 million per year—more than the entire market capitalization of the four largest coal companies operating in the basin. It may seem as if the coal industry is hurting today, but it’s nothing compared to the bloodbath those companies would be facing if those ports had been built.

Obviously, this isn’t a story that you’ll hear the coal industry tell in public, except in an unguarded moment. They’ve continued to complain that environmentalists are killing jobs, stifling a great business opportunity, and so on. That story line, while false, lets coal industry executives blame their own poor business judgment on someone else.

But the truth is that coal exports are lousy business. There’s simply no money to be made in shipping Powder River Basin coal to Asia. There hasn’t been for years. The only thing that would-be exporters can do now is hope that the Asian coal bubble re-inflates for long enough for them to get rich, and then get out before it pops once again.

Coal ship. Photo credit nothingexceptionalhere. Coal ship by Edward Jung used under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

KAC

The facts and figures cited in the article are robust and self-explanatory: coal production export are financially lethal to the exporting companies. Given that, why does the Gateway Pacific consortium continue to press so vigorously for construction of the terminal?

Shira

Gateway Pacific Terminal was originally planned as a bulk terminal for the grain that is grown in the northern tier of states. The whole coal terminal aspect must have seemed like a fortuitous opportunity at the time. Now that shipping coal to China is a money losing proposition, the grain from the northern states is still bottlenecked. Bellingham is still the only place this far north and in the US, where the land with its railhead meet a potential deep water port.