After a brief bubble of enthusiasm a few years back, the prospects for Northwest coal exports have dimmed dramatically. But despite wave after wave of dismal news for would-be exporters, the developers of massive coal export terminals in Washington and British Columbia keep marching forward, bound and determined to see their projects approved, built, operational, and channeling upwards of 100 million metric tons of coal from Wyoming and Montana westward across the Pacific each year.

Just for argument’s sake, let’s assume that would-be coal exporters succeed in building these coal terminals, despite the long odds. Just how much climate-warming CO2 would be emitted into the atmosphere as a result?

There’s no easy answer. On the one hand, an influx of US coal into Pacific Rim markets might prompt export cutbacks from Russia, Indonesia, or Australia, partially canceling out the climate impacts of US exports. On the other hand, abundant US coal supplies at stable prices could also spur Asian nations to build new coal-fired power plants, or run existing coal plants more intensively. And adding huge amounts of US coal to the Pacific Rim could even curb efforts to boost energy efficiency, or undermine the development of solar, wind, or other low-carbon alternatives to coal. Any of those outcomes would increase coal demand and boost long-term emissions.

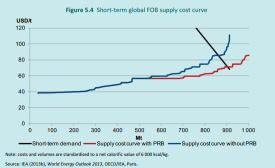

A few years back, the International Energy Agency (IEA) took a stab at predicting how these two countervailing forces—supply substitution vs. induced demand—might balance out in practice. (See Box 5.2 of the agency’s 2013 Medium Term Coal Market Report.) The agency used comprehensive data on global coal supply costs, coupled with a model of the global energy economy, to estimate how the injection of massive Northwest export capacity might affect the overall consumption of coal in the Pacific Rim and across the globe.

The IEA’s conclusions got surprisingly little attention when first published, given how sobering they were. The agency found that the proposed Northwest coal ports—such as the massive Gateway Pacific and Millennium projects in Washington, or the smaller projects such as Fraser Surrey Docks—could boost long-term climate-warming emissions by 20 billion metric tons.

Insert your best Dr. Evil impression here.

How much is 20 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide? At last count, Washington’s economy emitted about 92 million tons of carbon per year. So by IEA’s estimates, over the long haul, Northwest coal ports could be responsible for more than 200 times as much carbon pollution as the entire state of Washington emits in a year.

Even more shockingly, 20 billion metric tons is about two-thirds as much CO2 as the entire globe emitted from fossil fuels in 2010. That Dr. Evil laugh is starting to sound pretty accurate right now.

Should we trust the IEA estimates? To a first approximation, I think we should.

Admittedly, the agency gets all sorts of forecasts wrong. Take, for example, the way they’ve consistently underestimated the growth of solar and wind power for well over a decade.

Still, IEA’s coal export estimates are broadly consonant with the analysis from Power Consulting, who examined the same questions. They’re also somewhat consistent with a recent Draft Environmental Impact Statement for a new coal mining project proposed in Montana, which attempted to study how abundant US coal exports could affect global coal demand.

Regardless of whether the IEA got its numbers exactly right, they’ve certainly made an important contribution to the debate over Pacific Northwest coal exports. By looking at the interplay of supply and demand, they’ve offered a glimpse of the climate-warming pollution that might be unleashed by the construction of Northwest coal terminals.

So if you like the idea of boosting global climate-warming emissions by the equivalent of 8 months of fossil fuel consumption by the entire globe, you’ll love Northwest coal terminals. But if you actually want to live here on planet earth, you might think that pumping that much carbon into the atmosphere is an irresponsible, unjustifiable, and generally crummy idea.

Comments are closed.