[prettyquote align=right]”We can put the power back where it belongs: with voters.”[/prettyquote]

Do you ever think about just not voting, and then feel bad for being lazy? Or do you wonder what is wrong with your friends who don’t exercise their right to vote? Last time, I made the case that politicians aren’t bad apples, our voting system is a bad barrel. That bad barrel also taints voters, making them more apathetic, disengaged, and suspicious that the whole system is corrupted by money. In this article, I lay out more problems and solutions: voters feel like their votes don’t matter and money has too much influence, but a better voting system can engage voters and make money matter less.

Problem: Most election results are already decided before voters get the chance to vote in the general election.

Many countries have used the “election-before-the-election” as a tool for disenfranchising voters while still going through the motions of letting them vote. In the United States after the Civil War, Southern states could no longer legally prohibit people of color from voting. Instead, Southern states used “white primaries” to ensure that only white-approved candidates would be on the ballot. People of color could vote in the general election, but the real decisions had already been made. China recently used this tool against Hong Kong. China agreed to let all Hong Kong voters choose their chief executive. From a China-approved list of candidates.

In the United States, we still have systems ensuring that a select few pre-approve all the candidates before most people vote. We have party primaries. (We also have the money primary—more on money next.)

Most US districts are “safe” for one of the two major parties because the district boundaries have been drawn to give one party a decisive advantage. This is not just gerrymandering—even independent redistricting commissions in Washington state drawing lines around contiguous communities create “safe” districts because communities are increasingly sorted by ideology. In a safe district, the primary for the dominant party is the real election. In 94 percent of US House general elections, whoever won the dominant party primary will win the general election. Voters in the general election are just a rubber stamp. Even spending more money can’t overcome partisanship. Idaho, Oregon, and Washington had zero competitive seats in 2014: 11 of their collective 17 congressional districts are completely safe, with greater than 58 percent of voters voting for one party, and the remaining 5 seats are fairly safe, with 53 to 58 percent advantage to one party. In 2016, American voters will only have the opportunity to really choose a candidate, rather than rubber-stamp a pre-determined candidate, in just 3 percent of House seats. Only one Cascadian seat—Washington District 1—will actually be a race in 2016.

Elections for executive office, like Governor, are more competitive because safe districts don’t protect them and partisans are more likely to “throw the bums out” when the state has had a rocky few years. So maybe your vote counts? Or not: the presidential candidate with less popular support may win due to the ghastly electoral college, or a candidate with less than majority support may be installed in office because of the spoiler problem (as when Nader spoiled the election for Gore and installed Bush). Sigh.

It’s hard to get excited about voting in a general election when, odds are, your vote really will not matter.

Solution: Ensure that support from more general election votes makes a candidate more likely to win.

[prettyquote align=right]”Voters, not district boundary lines, should determine who wins elections.”[/prettyquote]

Voters, not district boundary lines, should determine who wins elections. General elections, not party primaries, should elect legislators. With multi-winner districts, it is nearly impossible to pre-determine the election outcomes just by drawing the district boundaries. All voters have a shot at electing one or more representatives for their district, meaning it matters whether they vote and whom they vote for.

Ranked-choice voting eliminates the need for primaries, or enables open top four primaries that give November voters more choices than the two provided in California and Washington because the run-off is built into the vote. General election voters can actually choose winners, rather than rubber-stamping a ballot hand-picked by primary voters.

With ranked-choice voting for executive office, a candidate can’t take office without support from a majority of voters. So voters can vote their true preferences, safe in the knowledge that the candidate with the most true support will win.

Problem: Voters are unrepresented and disengaged.

Low voter turnout has historically plagued the United States, and to some extent, Canada. If you are a member of the smaller party in a safe district—as more than 40 percent of Oregon and Washington voters are—winner-take-all elections have nothing to offer you. You can vote in every election and never once put someone in office who represents your views. If you align with a third-party, your candidate almost never has a shot at winning. You could choose to strategically vote for the lesser of two evils. Or just not vote. Why vote, if you can’t actually elect someone to represent you?

Solution: Make more votes count.

In a multi-winner district, more voters have the chance to elect at least one representative. The power to elect makes voting more attractive, boosting voter knowledge and turnout.

In a single-winner election with ranked-choice voting, voters can safely vote for their favorite long shot candidate without wasting their votes. They can use their second-ranked vote to help push another candidate they like, but who is more popular, over the finish line. The freedom to vote your true preference is more motivating than holding your nose and voting for the lesser of two evils.

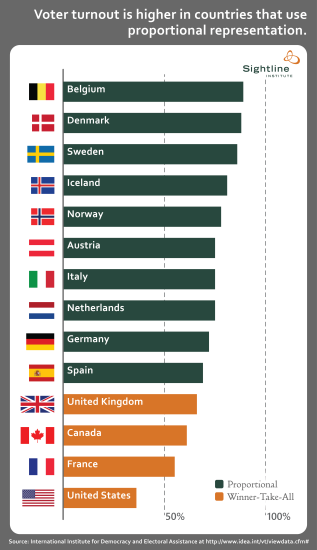

Experience shows that countries with proportional representation have consistently higher voter turnout than countries with winner-take-all. And, by the way, countries with winner-take-all are a small and discontented club: only the United States, Canada, Great Britain, and France still use it.

Problem: Voters know that money is corrupting our democracy.

Money corrupts. Thanks to a series of Supreme Court decisions, more money is flowing into American elections every year: the 2014 mid-terms cost $4 billion, and the 2016 presidential election alone is likely to cost $10 billion, with the Koch brothers’ fund shoveling in nearly $1 billion. The spending seems to work: in 2012, 95 percent of the US House candidates who spent more money won their election. Most of the money accompanying legislators to victory comes from the richest 0.01 percent of the population, and it shows: government policies overwhelmingly benefit businesses and the wealthy over the middle class.

Solution: Make money matter less.

Money and winning go together. It could be that a candidate can win if he raises more money. Or perhaps a candidate can raise more money if he is already sure to win. Most elections are safe, and the safe winner raises the most money about 90 percent of the time. But in the few races that are not safe, the big spender only wins about 60 percent of the time. Campaign funders may not be paying to help their favorite candidate win so much as they are using campaign donations as a way to lobby the soon-to-be winner. By removing safe seats, proportional representation may make campaign finance a less attractive form of lobbying, causing funders to save some of their cash.

[prettyquote align=right]”The candidate who spends less money wins a ranked-choice election five out of six times.” -@FairVote[/prettyquote]

Ranked-choice voting also undercuts the sway that money now holds in elections. Ranked-choice voting rewards candidates who engage in direct contact with voters over those who simply shell out the money for 30-second television ads. One example was Betsy Hodges’ upset win in the 2013 Minneapolis mayoral race. Hodges won by 20 percentage points in the final round of the RCV tally even while not spending money on television advertising, unlike the better-funded frontrunner. Her campaign instead invested in direct voter contact. Oakland Mayor Jean Quan also used direct voter engagement (“we talked to everyone” she said) to win the most support from voters despite being outspent nearly four to one: her campaign and independent supporters spent $275,000 while Don Perata’s campaign and supporters spent nearly $1 million. Indeed, according to a forthcoming FairVote analysis, the candidate who spends less money wins a ranked-choice election five out of six times.

North American voters aren’t more lazy and apathetic than voters in other countries. Rather, voters sense that the archaic voting systems still in place in the United States and Canada strengthen the power of parties and plutocrats and diminish the power of the people’s votes. By implementing multi-winner districts and ranked-choice voting throughout Cascadia, we can put the power back where it belongs: with voters.

Thanks to FairVote for its decades of research on proportional representation and ranked-choice voting. This article relies heavily on that research.

Comments are closed.