In the Northwest, as across the United States, political giving is an elite affair, heavily concentrated among one percenters and residents of affluent, white neighborhoods. Even in Seattle, which has more campaign participation than most places, only 1.7 percent of adults made a contribution to any local candidate in the last municipal election, in 2013. Half of those people made contributions, to all candidates combined, of $100 or less.

Vouchers could be a huge boost for participatory democracy.

Honest Elections Seattle’s Democracy Voucher program could change all that, though, multiplying the number of residents who give to campaigns and expanding the geography of contributors to the whole city. Vouchers could be a huge boost for participatory democracy. Another day, I’ll lay out the specific case of Seattle, complete with maps and statistics. Today, I describe how public funding has transformed campaign giving in New York City. In the Big Apple, candidates for state assembly and city council run in districts of similar size and in similarly competitive races. Candidates for state assembly raise money the old-fashioned way: dialing for dollars. Candidates for city council, in contrast, raise money through a system of public-matching funds for small-dollar contributions. The first $175 of any resident’s gift is matched six-to-one with public funds. This one difference makes New York a fascinating natural experiment in how public campaign funds change politics.

Money Maps

Candidates for both council and assembly raised money from big-dollar donors. In both cases, many of these contributors live in the toniest precinct, such as the Upper East and West Sides of Manhattan, as shown in this animated map. (The map displays all neighborhoods from which at least one $1,000 contribution was made to an assembly or council candidate. “Neighborhood” is defined as a census block group, an area of several city blocks. “Census block groups” are defined by a constant population, not a geographic area, so they are bigger on Staten Island and other farther-out boroughs where population density is lower. They are smaller in Manhattan and other central parts of the city.) Council candidates raised a little more money than assembly candidates, on average, and therefore the council-donor map lights up more neighborhoods than the assembly map. Overall, though, the differences between the two maps are modest.

Small-dollar contributions, however, followed a completely different pattern, as this second animated map (below) illustrates. State assembly candidates raised their small-donor gifts mostly from the same favored districts as their major-donor gifts. Their small contributions were side benefits of hustling for big money. They collected small-dollar contributions from just 30 percent of the city’s neighborhoods. City council candidates, however, raised small-dollar contributions from every part of the city, from almost 90 percent of neighborhoods.

The Brennan Center for Justice at New York University Law School and the Campaign Finance Institute in Washington, DC, which conducted the analysis for these maps, note:

Almost everyone in the city, from the richest of neighborhoods to the poorest, lived within a city block or so of someone who contributed to the 2009 City Council elections. The donors looked and lived like the neighbors in everyone’s neighborhoods, because they came from literally all over the city. This was not even close to being true for the donors in the 2010 New York State Assembly elections.

Candidates who have run in both city council and state assembly elections testify to the different incentives that the city’s small-donor matching-fund system creates. Said Eric Adams, a New York State Senator then running for city office:

On the state level, I’m targeting people who are in politics, either as lobbyists or unions or corporations…. If I reach out to a lobbyist, I may be able to get a $2,000 check in comparison to reaching out to a single person who could only write a $50 or a $100 check. So the bulk of my time would probably go to those professionals in the business of politics…. It’s just the opposite in the city… most of my calls are to small donors: everyday people. And a large number of people who contribute to my campaign have never contributed to a campaign before; have never really participated in politics.

The Color of Money

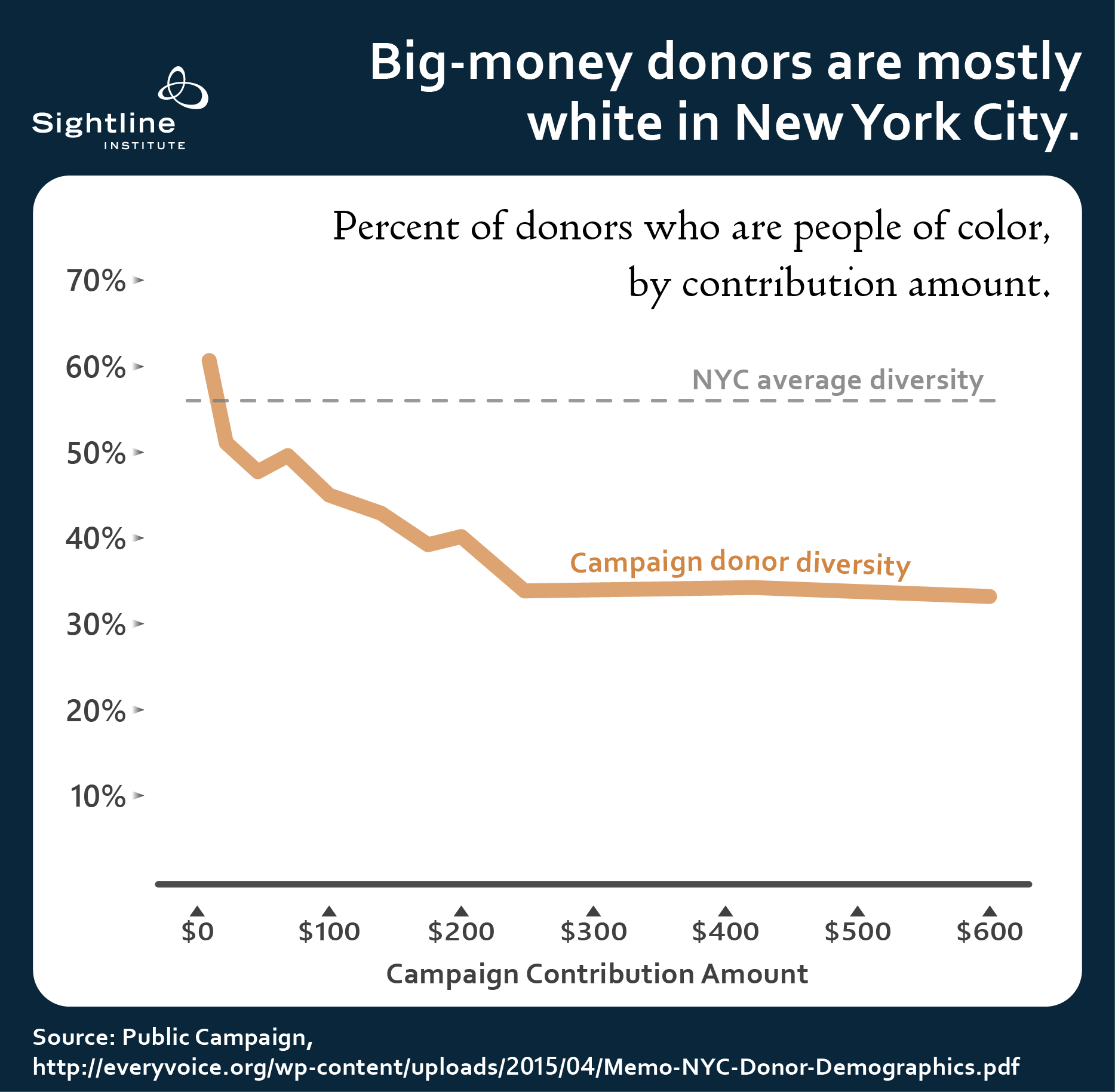

Compared with big-money contributions, small-dollar contributions come not only from different places but from different people. In predominantly African-American Bedford Stuyvesant, for example, 24 times as many people made small contributions to city council candidates, who courted them because of the matching-fund program, as to state assembly campaigns. The national reform group Public Campaign also examined the demographics of contributors to New York campaigns, extrapolating those demographic characteristics from donors’ home address and fine-grain census data on those census block groups. The figure below summarizes the group’s findings: the larger the contribution, the more likely it comes from a white person. The smallest donations—those for $10 or $25—come from people who match the city’s racial and ethnic diversity. Racial and ethnic diversity plummets as gifts grow. Once the gift amount is $250, odds are good that the contributor is white. Similarly, Public Campaign found that as the gift size increases beyond $250, the contributor’s income soars above the city average.

New York Alki

The founders of the city of Seattle, the Denny Party, named their first land claim “New York Alki,” meaning “New York, by and by” in Chinook jargon. They were an aspiring lot, no doubt, and Seattle has certainly grown, if not to Gotham proportions. By and by, though, Honest Elections Seattle could make public participation in political campaigns equal or even exceed that in the Big Apple. Vouchers are even more powerfully democratizing than matching funds because they do not require the donor to spend any of his or her own money. They are free, from the contributor’s perspective. Next time, I’ll show how they could redraw the political map of the Emerald City.

Thanks to the Brennan Center, the Campaign Finance Institute, and Public Campaign for permission to adapt and publish their maps and chart.

Comments are closed.