Residential construction is booming again in Seattle and other Northwest cities. To make way for the new, as well as needed increases in density, hundreds of older homes are being demolished every year. However, poor demolition practices—even by “green” builders—and lax regulation are creating an unnecessary hazard from lead-based paint.

Removing older or poorly maintained homes from the housing stock can be a good thing, in the long run, to prevent childhood exposure to lead-based paint dust—a highly potent neurotoxin that study after study has shown can cause life-changing effects in children even when they’re exposed to very small amounts. But improperly handled demolitions can create shorter-term risks. If you see clouds of dust at a construction site where an older home is being torn down, you are likely seeing the spread of airborne lead dust.

[prettyquote align=”right”]“No safe blood lead level in children has been identified. Even low levels of lead in blood have been shown to affect IQ, ability to pay attention, and academic achievement. And effects of lead exposure cannot be corrected.”—Centers for Disease Control, Healthy Homes and Lead Program, 2014. [/prettyquote]

A 2013 study of Chicago single-family home demolitions by David Jacobs, a leading expert on lead-based paint and housing, concludes that “large amounts of dust contaminated with lead and other heavy metals are generated from demolition of older housing.” When an excavator tears into an older home, lead that was once spread across walls, windowsills, and other surfaces in the form of paint gets pulverized into dust. And if relatively simple steps aren’t taken to control it, the contaminated dust can become airborne and settle on nearby yards, homes, sidewalks, and playgrounds.

Demolition lead dust that gets tracked into neighboring homes and finds its way into children’s bodies can increase children’s blood lead levels, especially in neighborhoods where multiple homes are being torn down. And toxic particles can travel far from demolition sites—up to 400 feet if conditions are right, according to Jacobs’ study.

Yet due to a loophole big enough to drive a backhoe through, knocking down an entire older home covered in lead-based paint in a single day doesn’t trigger any of the same health precautions as a construction crew would have to take if they remodeled the kitchen in that same house.

‘Hundreds of pounds’ of lead on the walls

Lead in paint was outlawed in the US in 1978. Before that, paint had lots of it. In general, the older the house, the higher the lead-based paint content. In the first half of the twentieth century, up to 70 percent of a can of paint was composed of lead pigments. Here’s how public health historian David Rosner puts it:

When you lifted [a can of paint] in your grandfather’s garage…it was very, very heavy. And that’s because in that can of paint there was 15 pounds of lead. And that was being painted on walls, three coats on each wall, every five to ten years, whenever the renovation took place. We were putting on literally hundreds and hundreds of pounds of lead.

A Centers for Disease Control advisory committee concluded in 2012 that there is no known level of lead in kids’ blood that isn’t harmful. The CDC now states that blood lead levels once considered very low can cause irreversible damage. And a child suffering from lead poisoning may not show immediate outward symptoms, even after exposure to levels that have been shown to later reduce IQ and alter behavior.

The health threats from legacy lead paint are serious enough that the EPA’s Renovation, Repair & Painting (RRP) Rule requires contractors to take extra precautions when working on any home built before 1978. Whether they’re remodeling a kitchen, repairing drywall, or sanding trim, workers must follow special procedures if they disturb more than six square feet inside the house or 20 square feet of exterior paint. Those include becoming certified in lead-safe practices, notifying tenants of potential hazards, keeping other people and pets out of the work area, and taking steps to prevent lead-based paint dust from contaminating other areas of the house or neighborhood.

Yet those rules only apply to remodeling and repair jobs. Surprisingly, none of those requirements apply to whole house demolitions.

Demolition a go-go

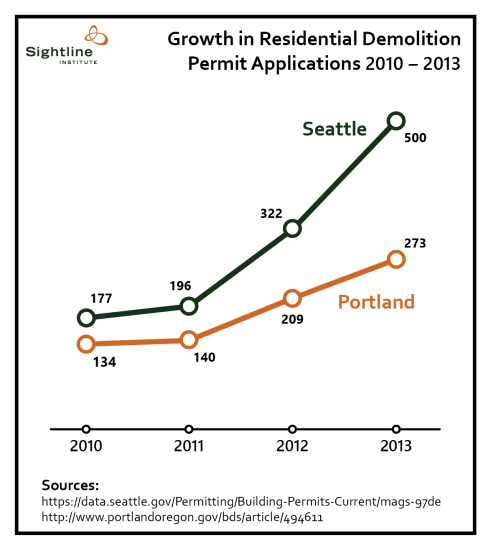

Meanwhile, as economic prospects have risen over the last several years, so have residential demolitions in Northwest cities. Portland, for instance, is on track to see a 40 percent jump in home demolitions this year. The average year that those homes were built is 1927—right in the era with the highest use of lead-based paint. Seattle builders filed 500 residential demolition permit applications in 2013 and 481 as of mid-October 2014, almost all of which are for older homes.

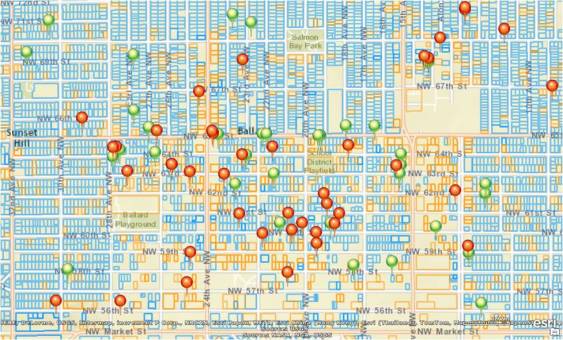

The map on the left (click here to embiggen) shows all the recent residential demolition permit applications filed with Seattle’s Department of Planning and Development. Green pins show demolition permit applications filed in 2013, and the red pins show applications filed before mid-October in 2014.

To find out what’s been happening in Portland, you can see a map of residential demolition activity back to 1996 here.

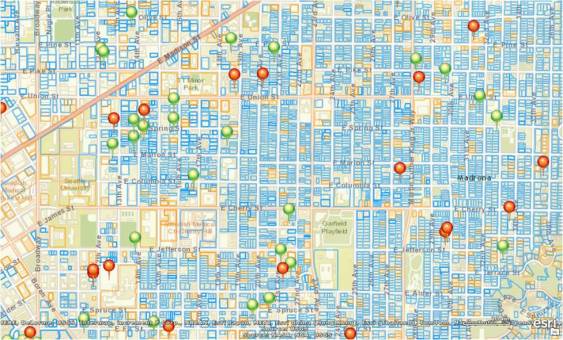

The demolitions tend to be concentrated in close-in neighborhoods, which have higher numbers of older homes. That potentially increases the level of exposure to lead-based paint dust from multiple demolitions.

As an example, here’s a closer look at demolition permit applications in the heart of Seattle’s Ballard neighborhood, where developers have applied to knock down dozens of older homes over the past two years. (Note: Blue parcels have homes built before 1950, which are more likely to contain lead-based paint. Yellow parcels have structures built between 1950 and 1977.)

And a look at demolition permit activity in Seattle’s Central District neighborhood:

Regulatory catch 22s

In Northwest cities, there is a catch 22 when it comes to regulating health hazards associated with demolition. The local building departments in Seattle and Portland defer to the state agencies (here and here) that enforce the EPA’s lead-based paint rules. But the federal law only applies to renovations and repairs, and those agencies haven’t been granted authority at the state level to enforce lead-safe practices for whole house demolitions.

The building departments also point to the state clean air agencies. Demolition dust could be considered an air emission and regulated under a state’s clean air act. But state agencies charged with air pollution enforcement like the Puget Sound Clean Air Agency have chosen not to monitor or regulate demolitions for lead dust. Their focus is on asbestos.

Some regulations and incentives aim to promote deconstruction and maximize recycling of demolition debris, but these primarily focus on reducing waste, not on minimizing neighborhood health risks.

Worker safety laws do address some construction-related lead hazards, though it’s unclear how often those rules are enforced. Debris from a demolition site—if heavily leaded—must be disposed of under state hazardous waste rules. But none of those rules are focused on protecting the public from fugitive lead-based paint dust during the demolition process.

Similarly, construction crews are required to take steps to keep pollutants like demolition dust from getting into stormwater, but those regulations don’t squarely aim at reducing potential neighborhood contamination from lead.

Ironically, many of the older home demolitions that are potentially spreading toxic dust in neighborhoods and putting children at risk are for new structures that are billed as green.

A self-proclaimed “green” builder, BuiltGreen, or other green building standard doesn’t guarantee any reasonable environmental practice when it comes to demolition. Checklists and verification processes for BuiltGreen, which can earn the new home builder extra development capacity or higher prices, don’t cover responsible demolition practices. These green building rating systems presume that the builder will simply follow laws covering lead-based paint and hazardous waste. However, because of the catch 22 and demolition loophole, that presumption is incorrect.

What we can do

The good news is that it’s feasible and inexpensive to minimize lead dust dispersal from demolition. Jacobs reports in his study of single-family older housing demolitions that lead dust fall was 2.5 times lower for sites where basic dust suppression was used, and much lower with enhanced techniques.

A key factor, according to Jacobs’ study, is the level of water applied on the demolition site. More wetting equals less dust. This means using fire hoses for dust suppression connected to hydrants or water trucks sprayed on debris, carts and structures—not a slight stream from a residential garden hose. A demolition done during a rainy day will have less dust dispersal than one done on a sunny, windy day.

With authorization from their legislatures, state lead-based paint programs could require construction crews to follow lead-safe demolition practices. And state clean air agencies, which are already regulating demolition for asbestos emissions, could incorporate similar rules for lead dust.

At the heart of addressing toxic emissions from demolition is effective community notification, as well as changing developer and contractor practices. There will never be enough inspectors to be onsite at each demolition, so giving neighbors the tools to monitor demolitions through advance notice is key. In Portland, the high rate of residential demolition galvanized residents and groups like Southeast Uplift to demand a Demolition Delay and Notification ordinance.

If you live in Seattle, demolition notification is pretty minimal. You might see a mention of a demolition in your neighborhood via a notice or board posted at the site. You can look up the DPD demolition permit, which will have the contact for the developer, whom you can call to attempt to find out the actual day of demolition. The age of the house being torn down is not included in the DPD permit—for that you will need to go to the county assessor’s website.

Jacobs, based on his findings, recommends that notification “should be expanded to at least 400 feet away from single-family housing demolition, not just adjacent properties.” Here’s what notification would look like in Ballard if Jacobs’ recommendations were followed:

The nonprofit East Baltimore Development, Inc. (EBDI) has also developed a sophisticated responsible demolition protocol that agencies, green builders, and others can adopt. According to Jacobs in his 2013 study, lead dust dispersal levels at demolition sites that took these steps were 56 times lower than demolitions with no dust control.

Principles of Responsible Demolition based on EBDI Demolition Protocols

- Provide effective, advanced community notification with actual date of demolition.

- Use adequate amounts of water to suppress dust during demolition. (Seattle makes it pretty easy for builders to obtain a hydrant permit.)

- Remove doors, windows, railings, and other components with high amounts of lead before demolition.

- Use fencing and other barriers to control the spread of dust during and after demolition and keep children and other pedestrians away from the site.

- Cover all trucks carting debris out of the neighborhood.

- Replace contaminated soil with new sod to eliminate topsoil contaminated during the demolition process.

- Ensure that someone on the demolition crew is charged with ensuring that dust minimization practices are followed.

- Require independent testing.

Green builders do many things above and beyond what is required by building and energy codes. They are rewarded for it with expedited permits, land use incentives, and marketing advantages with environmentally minded home buyers. Making sure older home demolition is done right and kids are not harmed should be a basic requirement for green building rating systems and third party auditing.

Preventing harmful childhood exposure to lead and other neurotoxins needs to be an integral part of early childhood policies. Stopping lead-based paint dust from demolition is a relatively easy piece to accomplish in a prevention agenda.

Comments are closed.