Last time, I shared the #1 question from conservatives about revenue-neutral carbon taxes like the Carbon Washington proposal to implement a BC-style carbon tax and use the revenue to cut sales taxes and business taxes:

How do you know it’s going to stay revenue-neutral?

This time I’d like to share with you the #1 question from progressives about revenue-neutral carbon taxes:

How do you know it’s going to stay revenue-neutral?

It’s the same question! The motivations for asking the question, of course, are different. Conservatives ask because they’re worried about government getting bigger, that is, when we compare revenues from the existing tax system X with revenues from a potential new tax system Y, they want to make sure that X ≥ Y. Progressives ask because they’re worried about government getting smaller, that is, they want to make sure that X ≤ Y.

All of this makes total sense given that the goal of revenue neutrality is to sidestep the argument about whether government is too big or too small by aiming for X = Y. Folks on both sides of that debate are going to come at it from their own perspective.

Last time, I offered my best answer to the conservative concerns about revenue neutrality. This time, I tackle the progressive concerns by looking at how carbon tax revenue measures up to potential tax reductions now and in the future. I focus on Washington, but a similar analysis would apply in Oregon or other jurisdictions.

In the now, the Carbon Washington proposal would generate about $1.7 billion a year in revenue, or about 10 percent of state government revenue. It would cut the state sales tax by one full percentage point ($1.3 billion a year), fund the Working Families sales tax rebate ($200 million), and effectively eliminate the B&O business tax for manufacturers ($200 million). Add it up, and the numbers balance.

But what about later? Will carbon tax revenues grow fast enough to fill the hole left by those tax reductions? That hole is likely to grow over time, because of economic growth, population growth, and inflation. In contrast, tax revenue from a fixed carbon tax will hopefully shrink; after all, the point of climate policy is to reduce carbon emissions!

The Carbon Washington proposal addresses this issue by relying on a carbon tax rate that increases over time. So the key question is: What percentage increase in the rate of the carbon tax is likely to be sufficient to keep up with both the expected decrease in the base of the carbon tax (as carbon emissions decline) and the expected increase in the value of the tax reductions the carbon tax is intended to fund?

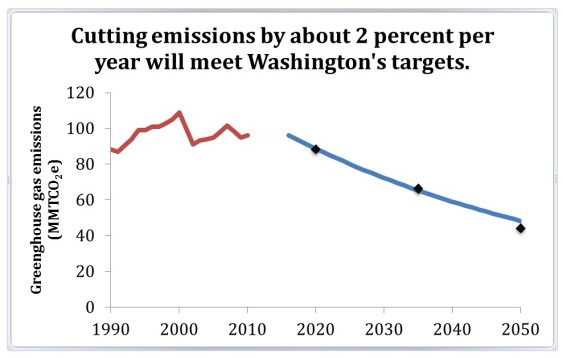

We don’t know for sure how fast carbon emissions will decline, but let’s take as an example the targets established by law in Washington: carbon emissions that are down to 1990 levels by 2020, to 75 percent of 1990 levels by 2035, and to 50 percent of 1990 levels by 2050.

The figure below estimates historic emissions (in red), the targets for 2020, 2035, and 2050 (in black), and the time path of emissions if we assume that emissions are flat between 2010 and 2016—we don’t yet have data for this period, but it will pre-date any carbon pricing policy—and then decline at 2 percent per year (in blue). The math shows that meeting these targets means cutting emissions by about 2 percent per year between now and 2050.

Source: Estimated from Department of Ecology, Washington State Greenhouse Gas Emissions Inventory 2009-2010. Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our Free Use Policy.

As for the value of the tax reductions that the carbon tax is intended to fund, the dominant contributor is the one-point reduction in the state sales tax. Washington State sales tax revenue has grown by a bit more than 3 percent per year since 1996. Revenue from the B&O (business) tax has grown by closer to 4 percent per year, so let’s put the weighted average at 3.5 percent.

Source: Washington State Department of Revenue, Tax Statistics 2013. Original Sightline Institute graphic, available under our Free Use Policy.

We now have an algebra problem: If the carbon tax base declines by 2 percent per year and revenue from sales and business taxes increases by 3.5 percent per year, how fast does the carbon tax rate need to rise to keep up?

The answer is about 5.5 percent per year. (Ask a teenager to show you that it’s actually 5.61 percent.) That’s not far off from the current Carbon Washington proposal of a 5 percent annual increase. (When updated tax statistics are available towards the end of the year, Carbon Washington intends to revisit these numbers and adjust the proposal accordingly.) This increase is not terribly aggressive in dollar terms. At 5.5 percent it will take more than 25 years for the tax to grow from $25 per ton to $100 per ton. And that’s without adjusting for inflation: assuming 2 percent annual inflation, the real value of a tax increasing at 5.5 percent would not hit $100 per ton for more than 40 years.

Three closing points

- Revenue neutrality will be harder to maintain over the very long term, just because there’s growing uncertainty about everything over time: economic growth, technological change, carbon emissions, population—everything.

- Uncertainty applies to the entire tax system, not just carbon tax swaps. For example, if everyone switches to electric cars, not only the carbon tax but also the gas tax will stop generating cash for the state treasury, shorting state highway budgets. In the long run, democracies have to reform their revenue systems.

- In Washington, current state tax revenue is about $17 billion a year. Total state revenue is about $34 billion a year because of federal government transfers and other budget items. So a $1.7 billion carbon tax is about 10 percent of state tax revenue and about 5 percent of the state budget. If carbon tax revenue turns out to be off—one way or the other—by 10 percent, that discrepancy amounts to 1 percent of state tax revenues or 0.5 percent of the state budget. That’s a problem for state budget writers, but no more of a problem than swings in expected revenue from existing taxes. And carbon tax revenues would likely be no harder to predict than any other revenue stream.

In short, a carbon tax swap is unlikely to change the general result we saw last time. Namely, government revenue as a percentage of personal income is basically flat at the local, state, and federal levels. And the best evidence available to us indicates that a revenue-neutral carbon tax would not change that. If you flip a coin 10 times, you may end up with more than 5 heads, or less than 5 heads, but in a mathematical sense you should expect to get 5 heads. In the same way, if a climate policy is designed to be revenue neutral, you should expect that it really will be revenue neutral.

Research assistance by Pablo Arenas and Summer Hanson. Technical note: As indicated above, greenhouse gas emissions for Washington State are estimated from this Ecology document, which includes a graph but no numerical data for 1991-2004. These data were estimated from the graph.

bill bradburd

being ‘revenue neutral’ in a state like Washington where we do not have ENOUGH revenue is not a good compromise…