A tax and a cap are just different vehicles for delivering the same thing: a carbon price that holds polluters responsible for their pollution, drives the transition to clean energy, andstaves off the worst risks of climate volatility. With a tax, you know the price in advance but not the quantity of carbon pollution per year; with a cap, you know the carbon but not the price.

Could Oregon and Washington create a cap-tax hybrid that is custom-made for the Pacific Northwest’s unique circumstances, culture, and economy? Northwesterners are down-to-earth and pragmatic, resilient through changing conditions. A Northwestern climate policy should be the same: taking the best aspects of what has come before (BC’s tax and California’s cap) and hybridizing them into a robust policy that can ride out the rainy days.

This article, the first of three about variations on carbon pricing, describes not just one but four cap-tax hybrids that could fit the Northwest like a fleece vest.

1. Use a self-adjusting tax to get the pollution cutting certainty of a cap.

Oregon or Washington could combine the price certainty of a tax with the pollution-slashing certainty of a cap. A self-adjusting tax is like the bumpers at the bowling alley. You pick a tax that aims for the carbon pollution trend to go right down the middle of the lane, but if your aim was bad, the automatic tax-rate adjustments act like bumpers, nudging pollution levels back on course. In Switzerland, a crude version of this approach is the law. The nation enacted a CO2tax in 2008 and later modified it to allow increases if the nation does not hit its carbon phaseout goals. Switzerland’s2012 ordinance set the tax at 36 Swiss francs (about US$37) per ton and authorized increases to 60 francs in 2014, 72 or 84 francs in 2016, and 96 francs in 2018. The federal environment agency automatically increased the tax to 60 francs in March 2013, because Swiss carbon pollution levels in 2012 hit the trigger threshold.

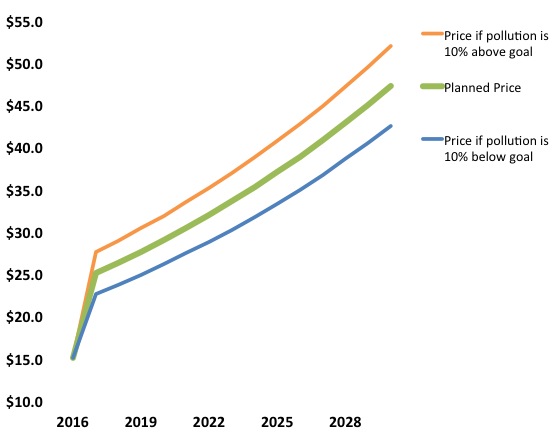

The Swiss plan has giant tax rate increases; the bumpers don’t just nudge, they whack the ball back into the lane. Oregon or Washington could implement a subtler and smoother automatic carbon tax: one with tailored, pre-determined, pollution-triggered price adjustments to ensure the state meets its pollution trimming goals. How might this work? One simple example: the planned tax rate trajectory could be like the one that CarbonWA advocates: starting at $15, then up to $25 the second year, then rising at the rate of inflation plus 5 percent per year, as California’s floor and reserve prices do. Every three years, an agency—perhaps the Department of Ecology in Washington or Oregon’s Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ)—would run the numbers to see whether the state is sticking to its legally mandated schedule for trimming carbon pollution. If pollution was more or less than expected, the tax rate would bump up or down by the same percentage. For example, if pollution dropped 10 percent more than expected between 2015 and 2017, the tax would automatically drop 10 percent from the planned rates for 2018-2020. It would be $24.80 per ton in 2018 instead of $27.60. The adjustments would be symmetrical, as illustrated in the chart below. If polluters spewed out 10 percent more carbon in 2015-2017 than allowed by law, the tax rate would step up by 10 percent in 2018-2020: $30.30 in 2018, instead of $27.60.

An even more sophisticated, made-in-the-Northwest version of this bowling-with-bumpers tax might employ rate adjustments that phased in tax increases and decreases or that only adjusted the rate of change in the tax rate, rather than the underlying rate itself. For example, if there was too much pollution in 2015-2017, the tax might increase at a rate of GDP plus 10 percent per year, rather than 5 percent, for 2018-2020. It’s easy to imagine refinements.

The important point is that this self-adjusting tax rate would give everyone price certainty within boundaries. Businesses would know the exact carbon price for the next three years, and they would know the price would be within a narrow range for each three-year period after that. This knowledge would allow them to make long-term investments based on the price. It would also ensure that Oregon or Washington would actually squeeze carbon pollution out of its economy on schedule—walking down the stairs to carbon-free at a predictable, measured pace. In other words, we’d get the simplicity and most of the price certainty of a carbon tax plus most of the climate-protection certainty of a carbon cap. And it’d be a uniquely Northwest solution, taking the best of BC and California.

[table “” not found /]| Pros | Cons |

| Price certainty, within bounds. | Price might be too high or too low for a few years at a time. |

| State will meet its carbon goals. | Pre-determined price changes might not be sufficient if the original price was too far off. |

| Gets close to lowest-cost cuts. | Less certain than un-adjusting tax on price; less certain than cap on carbon pollution. |

| Motivates clean energy investments because businesses know the price will continue. |

2. Adopt a cap but authorize a tax as a backstop.

Oregon or Washington could start with a cap and authorize a tax as a fallback. The legislation would require state agencies to move forward with the regulations needed to join California’s cap, but it would also spell out a carbon tax as a backstop. It could be an extremely simple carbon tax—almost a photocopy of the rules and regulations in British Columbia, for example. That way, tax authorities will not have to do drawn out rulemaking before launching the tax.

The legislation would also specify the conditions that would trigger the state to abandon the cap and implement the tax. For example, it could authorize the state revenue agency to begin collecting the tax on a specified date unless the state environmental agency first certified it had successfully joined California’s cap and met other criteria: for example, the plan does not contain loopholes that endanger the state’s legal commitment to its schedule of emissions reductions, and that there is no evidence of destructive gaming in the carbon market. Because the tax rate schedule was already authorized in the legislation, the switch could be fast.

[table “” not found /]| Pros | Cons |

| State will meet its carbon goals. | Price would not be in place for several years while agency goes through the rulemaking process. |

| Takes advantage of the existing cap. | More complicated than a cap or a tax alone. |

| Ensures action on climate. | |

| Protects against gaming or other problems with the cap. | |

| Motivates clean energy investments because businesses know the price will continue. |

3. Start with a tax and transition to a cap.

Oregon or Washington could start a carbon tax immediately, and transition to a cap in a few years. The cap could start on the CarbonWA trajectory explained above, for example, or on a path to quickly catch up with British Columbia’s current price of $30 per ton. This way the carbon price would already be in place as the state environmental agency went through its required public rulemaking to develop a cap. Once the cap regulations were ready, the tax rate then in effect would become the floor price in the state carbon auction. There would be no price volatility, as polluters would transition smoothly from paying a tax of, for example in 2018, $26 per ton to purchasing allowances for a minimum of $28 per ton in 2019.

CarbonWA or BC’s price trajectory would put Oregon or Washington’s floor price well above California’s floor price (currently $11.34), and likely above California’s auction price (currently $11.50). The state’s allowances would sell at their (higher) floor price for a few years until the market price caught up. This would create a price discrepancy between the states, but would ensure a quick and strong price signal as well as the certainty of keeping pollution under the cap. Alternatively, Oregon and Washington could set their starter tax rates to align with California’s auction price for allowances—a slower start in pricing carbon but one that would make the transition to a cap simpler.

[table “” not found /]| Pros | Cons |

| Price certainty for years. | More complicated than a cap or a tax alone. |

| State will meet its carbon goals. |

4. Implement a tax with a cap as a backstop.

Oregon or Washington could implement a tax but keep a cap at the ready. They could pass bills that authorize a carbon tax but also direct DEQ and Ecology to prepare the regulations needed to link to California and keep them on a shelf. Every three years, the agencies would review the tax to see whether it is paring pollution as needed. If pollution cuts fell short of pre-determined milestones, the state would abandon the tax and join California’s cap. This policy would allow a fast switch from tax to cap because the agency already had the cap ready to roll. It would prod stakeholders to push for a tax high enough to wring pollution from the economy on schedule, because an inadequate tax would trigger the launch of cap and trade.

On the downside, this backstop plan would create a lot of work for the agency to write regulations that might never be used. It might even cause some businesses to not only pay the tax but also purchase allowances as a hedge against future risk. To prevent these downsides, the legislation could retain the authority to cap, without ordering the agency to write the regulations immediately. The agency would wait until the first three-year check-up to see whether the tax worked. If it did not work, the tax would stay in place while the agency went through the rulemaking for the cap. Once the rules were ready, the state would abandon the tax and join the cap.

[table_container]

| Pros | Cons |

| Price certainty, if tax stays in place. | Potential for wasted agency efforts. |

| Ensures action on climate. | Duplicative compliance efforts by business that pay the tax and also purchase allowances as a hedge. |

| State will meet its climate goals. |

[/table_container]

Northwest Hybrid Vigor

Every one of these options offers some perks that a cap or tax alone doesn’t. Why stick with basic cable when you can bundle it with other services you want? Although they each could add value to the basic carbon pricing proposal, my personal favorite is number 1: the automatically self-adjusting carbon tax. It could start right away, send a clear signal that would spur immediate investments in clean energy, but elegantly course-correct to guide us to a cleaner economy and a safer climate.

The self-adjusting tax, with its calm resiliency to pollution ups and downs, is like northwesterners walking to work: we are prepared with a hood in case it pours or layers in case the sun comes out—but we’re going to get there rain or shine.

Comments are closed.