At last count, Seattle ranked as the fastest growing major city in America. The city’s growth has easily outpaced the projections of its decade-old Comprehensive Plan, which foresaw 47,000 new households (as well as 84,000 new jobs) between 2004 and 2024. Between 2005 and 2012 the city added 29,330 net new housing units—roughly 62 percent of its 2024 target in just 7 years.

This rapid growth has stemmed in large part from the city’s relatively robust economy. From March 2013 through March 2014, for example, King County (which includes Seattle) ranked fifth among all US counties in net job growth, trailing only the likes of Los Angeles County and Manhattan.

But the population boom has sent housing prices and rents trending upwards—creating real anxiety among many renters, and fears that Seattle’s housing market will price out residents that once could afford to live in the city.

One city councilmember has described today’s housing market as being in “crisis,” and the mayor has launched a housing affordability advisory committee aiming to make affordability recommendations by next March. (Full disclosure: Sightline Executive Director Alan Durning will serve on it.)

Zoned Out?

Very little in municipal policy creates as much controversy as zoning. Attempts to relax exclusionary housing rules—through upzones, unregulated microhousing development and other forms of inexpensive housing, or reducing the requirements to build parking for new housing—typically encounter resistance from existing residents. Because it’s often hard to change these exclusionary housing rules, municipal governments often turn to inclusionary zoning to try to soften the impact of exclusionary housing policies. But many developers (and some credible academics) view inclusionary zoning largely as a tax that adds to housing construction costs and stunts supply, which can ultimately boost rents rather than reducing them.

Discussions of housing affordability often revolve around questions of zoning—rules about who can build what kind of housing, where, with what sort of restrictions or requirements attached. Which raises some questions: where did zoning come from, and how do different places use it?

Zoning: Exclusionary and Inclusionary

Today zoning stands as the biggest blind spot of urban greens. But zoning of any kind is a relatively new practice in the United States. The nation’s first zoning codes originated in New York City in 1916, spurred by neighbors who opposed new high-rises. The use of zoning quickly spread to other municipalities. In 1926 the United States Supreme Court upheld the practice of zoning, ruling that the zoning laws of Euclid, Ohio, passed constitutional muster.

Many (but not all) of these early zoning programs were both racist and classist. They were largely created to keep “undesirable” people and development away from higher-income neighborhoods, by restricting both the types of housing that builders could build, and by restricting the kinds of people who could live in them. Over time, municipalities used zoning to reserve large swaths of their total land area for single family houses with ample yards—a particularly expensive form of housing, and one that limited the number of lower-income people who could afford to live near the well-off.

As a reaction to this sort of “exclusionary” zoning, in the early 1970s US municipalities began to adopt “inclusionary” zoning policies, which attempt to ensure that when new housing is built, developers provide low-cost housing for at least some residents. The first inclusionary zoning policy, passed in Fairfax County, Virginia in 1971, mandated that developers of more than 50 units of multi-family housing provide 15 percent of their units at prices that were affordable to residents within 60 to 80 percent of median income. In 1973, the Virginia Supreme Court overturned the ordinance, asserting that it was a “taking” of property rights without fair compensation. (See Fairfax County v. Degroff.) Nonetheless, in 1973 nearby Montgomery County, Maryland, passed a “moderately priced dwelling unit” ordinance, which required developers of more than 50 residential units to set aside 12.5 to 15 percent of total units, dispersed throughout the property and available to families with 50 to 80 percent of the area median income. It is still active.

The Montgomery County, Maryland, ordinance is the oldest in the United States. But California, with over one hundred ordinances and 30 years of experience, has the most familiarity with inclusionary zoning. The Bay Area standard bearer is Palo Alto, which first instituted its program in 1973. Today, more than 100 communities in California have similar zoning statutes. Nationally, the ordinances can also be found in Colorado, New Jersey, and Massachusetts, amongst other states.

Since 1999, Oregon jurisdictions have been prohibited from enacting mandatory inclusionary policies. Passed by the Oregon legislature, the prohibition was favored by home-builders and realtors who worried that inclusionary policies would hurt local housing markets. Oregon and Texas are the only two states that prevent municipalities from having a mandate on developers to provide subsidized housing in new construction.

Municipalities in British Columbia were among the first in Canada to adopt inclusionary zoning policies. Since 1988, Vancouver has required 20 percent of the units in major residential projects to be set aside for subsidized housing units.

Today, inclusionary zoning programs come in all shapes and sizes. Some offer incentives, such as the right to build more housing on a given property, provided that developers set aside some units that will be offered to lower-income people at below-market rates.

Sunset Electric Apartments, 11th and Pine, Seattle, WA by Joe Wolf used under CC BY-ND 2.0

The Sunset Electric Apartments in Seattle’s trendy Capitol Hill neighborhood were one of the first major projects in the area that took advantage of Seattle’s 2009 preservation incentive program, which granted developers a fifth floor of residential units in exchange for keeping the original 1926-constructed outer facade.

Other programs require developers to include below-market units in every new housing development. Some give developers a choice between building new units and paying into a municipal fund dedicated to building low-rent units. Inclusionary zoning programs differ in the types of development covered, the share of new units required, the required price for new rental units, who can obtain low-cost units, and the length of time that “affordable” units must be offered at below-market rates.

Many of these zoning programs require below-market units to be of similar size and quality as the market-price units, and also spread throughout the project to avoid creating conspicuous public housing or “projects”. However, New York City developers recently have generated national opprobrium by offering affordable units accessible only through “poor doors” separated from main entrances for market-rate units.

On Seattle’s Capitol Hill, Apartment for Rent Advert as Guerilla Art Installation. by Joe Wolf used under CC BY-ND 2.0

Seattle, like other cities grappling with rising home prices, is right to publicly discuss the merits of its various housing incentive programs. But leaving aside questions around inclusionary zoning, it’s clear that exclusionary housing policies still have a major effect on housing costs. No robust and honest debate on urban housing issues can avoid a thorough discussion of the ways that existing housing, parking, and zoning policies restrict the supply of low-cost housing—raising housing costs for everyone in the city.

RDPence

I remember a somewhat different history of zoning codes from my planning education many years ago. And that is that many early codes were driven by desires to separate incompatible land uses, particularly industrial uses and residential uses.

In those days air and noise pollution from factories and slaughter houses were totally unregulated, and homeowners and tenants wanted some assurances that such uses would not reduce the livability of residential neighborhoods.

While I’m sure that race and class distinctions played a role in zoning, especially in the Jim Crow south, even without those factors we would still have zoning codes in place today.

Sarajane Siegfriedt

Just delete the misdirected “especially in the Jim Crow south.” In fact, it was the racist North that prompted separation of the races most effectively. The history of HUD Fair Housing is one of billions in funding and zero enforcement ever since 1965, with the Fair Housing division being a career-killer for people of color bureaucrats.

See Nick Licata’s letter to Castro dated September 18th on his Web page

RDPence

Thanks for the added info, Sarajane. I was speaking only about the application of Euclidean zoning to enforce racial segregation. I wasn’t aware that northern cities were using that tool also. Time to expand my reading.

NickE

This is a great article, thanks Jerrell and Clark. I think it is very important for Mayor Murray and his housing affordability committee to hear the message that loosening restrictions on new supply of housing is crucial to making a dent in affordability.

Is this a position that Alan will put forth as part of the committee? I sure hope so.

Weezy

Don’t like the zoning here? Move to Houston.

NickE

I think there’s just a little bit of middle ground between zoning here and zoning in Houston, Weezy. I doubt you believe it’s that black and white. Houston has no growth boundary. We do, and that’s a good thing. But the regulations inside that boundary hamper housing density.

RDPence

“the regulations inside that [growth] boundary hamper housing density.” I’d like to see an honest discussion of which zoning regulations should be changed, and where, to increase housing density.

I keep hearing that Seattle has a few decades worth of zoning capacity. Does increasing that capacity even more really drive density?

NickE

Well RDPence, take Seattle as a microcosm. 65% of its land area is zoned for detached single family homes only, minimum lot size: 5,000 sf. That is a whole lot of area for really low density. It’s a discussion we can’t even have though because of politics and NIMBYism. If an elected official ever hinted at re-zoning some of that land, they’d be run out on a rail. Which is too bad because even a low-level upzone to something like Low-Rise 1/2/3 (for things like rowhomes, townhouses, duplexes) would inject massive amounts of capacity into the system.

That same thing happens outside Seattle too. We have a self-created housing shortage because we don’t want to live closer to each other so our houses are all really far apart and take up a lot of land.

Jerrell Whitehead

NickE,

Thanks for your interest on this post. The sequel to this article is now available. I am curious to see what you think of it.

I agree with you that less land in Seattle should be zoned for single-family houses. The number certainly should not be zero, but further research is needed to get the correct figure.

Politically, this will be difficult, but not impossible to achieve. Any politician looking to upzone significant portions of the city would need to proceed gradually, not thinking in a time scale of 1 to 5 years, but at least 10 to 20 years.

RDPence

Yes, NickE, lots of Seattle is zoned for and developed with SF housing. It’s not just zoning, it’s development and redevelopment. Drive around in some of those SF neighborhoods and you will see people fixing up their houses, including some adding ADUs and DADUs. Those neighborhoods don’t seem to be going away.

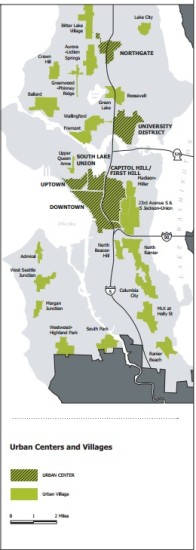

My question is still, where is the documented evidence that Seattle doesn’t have enough available development capacity in the remaining 35% of our land area? Or that additional needed development capacity cannot be accommodated by upzoning in the Urban Centers and Urban Villages, areas where most citizens agreed to accept higher densities? Why should anyone be targeting Seattle’s SF neighborhoods?

Matt the Engineer

1. It’s not 35%. You’re counting university space, industrial zoning, commercial zoning, hospitals, parks, etc. in that 35% number. Multifamily is 13.5%. And as for evidence, look at housing prices. Or even the new jobs v. new homes numbers in the table above. We have strong demand for housing, but little space for it.

RDPence

Lots of MF housing going up in NC zones and CBD zones, so the percentage land area at issue would be more than 13.5%.

I know the rhetoric, Matt; show me numbers. Evidence on the ground that there aren’t enough buildable sites outside of SF zones; no Urban Centers or Urban Villages that could be upzoned.

Just saying “but little space” doesn’t cut it. Show some credible evidence and then I could say, yes, let’s rezone some SF into MF.

Tom Lane

In terms of public policy, affordable housing rents should reflect the median income, household size, taxes, food costs, utilities, gasoline, and most importantly, whether the area has: 1) an emerging housing bubble, and 2) whether or not wages are gradually rising every year.

In Reno, you can work a minimum wage job for 40 hours a week and rent an apartment. However, this is not true in Seattle, since everything is more expensive, including rents (unless you live in Olympia or Bellingham, well outside the metro). Reno wages will increase, due to the recent approval of TESLA electric car manufacturing battery plant in Storey County east of Reno.

Some areas of the country are currently entering their second housing bubble, such as the five county area in Southern California … LA, Orange, Ventura, San Bernardino, and Riverside Counties. Riverside County provides a disturbing example of escalating rents, yet wages are not going up.

US Congressman Mark Takano (D-Riverside) has launched a Federal Investigation of the newest rent bubble in Riverside County. These statistics are alarming. Rents are going up while incomes are going down.

http://takano.house.gov/rent-on-the-rise-in-riverside

Cities such as Palm Springs, California, are not building enough affordable housing to reflect the fact that rents are going up, yet wages are not increasing. The Palm Springs and Coachella Valley region (460,000 persons in Riverside County) is intended for “rich retired folks.” Meanwhile, younger folks serving the rich, in retail and restaurant positions, are struggling to survive, due to increasing rents. Ultimately, they move to Arizona, Utah, and Colorado, where there are lower rents and higher paying jobs.

In addition, affordable housing policy should make sure that young creative people do not have to leave. Ventura County, California is an “aging oasis in paradise, writes Bill Watkins, Professor of Economics at California Lutheran University in Thousand Oaks, California. He writes,

“People – particularly in the late 20s and early 30s – aren’t leaving Ventura County because amenities have suddenly disappeared. They are leaving because of a deficit in opportunity. Their leaving has consequences. Ventura County’s population is aging more rapidly than it otherwise would. The net result of these demographic changes is that Ventura County’s median real per-capita income is declining, while the County’s median age is rising. Real per-capita personal income has fallen almost $1,000 in only eight years, to $32,718 (Constant 2000 dollars) from $33,797 in 2000.

It is losing its middle class and becoming bi-modal. The young families that provide a community’s vigor and future have been leaving.

The County is left with an aging and increasingly wealthy population along with the lower-income people that service the wealthy aged and the very-low-income farm workers. In a sense, it now resembles what we see in many expensive city cores – even if it is on the periphery!”

Just like with Riverside County, the young people are leaving Ventura County (which includes Ventura, Camarillo, Ojai, Thousand Oaks, and Simi Valley) –

“Generally, the lower-income population does not have the resources to provide leadership or invest in a community’s future. They have their hands full just taking care of their families, particularly in an expensive place like Ventura County. Their children will likely join the middle class, but in someplace more affordable like Texas, Arizona, or Nevada.”

“High concentrations of older people and declining incomes are often associated with deteriorating schools, amenities and increasing crime. The aged wealthy are not in Ventura County to invest in its future.”

Watkins continues by stating that the same phenomenon is occurring in Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo. Hopefully, Seattle’s leaders will learn from Dr. Watkins, and prevent this from happening in the Great Northwest.

Ref: http://www.newgeography.com/content/00631-the-aging-paradise-ventura-county-california

Finally, affordable housing programs should consider the GLBT population, since a recent survey shows strikingly high poverty rates, due to housing discrimination and other factors –

http://www.washingtonblade.com/2014/09/29/report-lgbt-americans-likely-live-poverty/