With a new school year approaching, this is a good time to update our review of the treatment of climate change in economics textbooks. As in our 2010 and 2012 reviews, some books hit the mark while others are wildly misleading. But we’re happy to say that there’s plenty of good news, especially at the top and the bottom of the grade distribution: the good books have gotten better (including the first-ever A+ grade!) and even the worst ones have made improvements (the lowest grade is now a D-, not a F!).

Some books, of course, suffered some backsliding. Out of 18 books reviewed, four still make the “Not Recommended” list, with the biggest loser being Gwartney, Stroup, Sobel, and Macpherson’s Economics: Private and Public Choice (15th ed.), hereby dubbed the recipient of the undesired 2014 Ruffin and Gregory Award for the Worst Treatment of Climate Change in an Economics Textbook (so named for a comically bad treatment of climate change in a textbook now thankfully out of print).

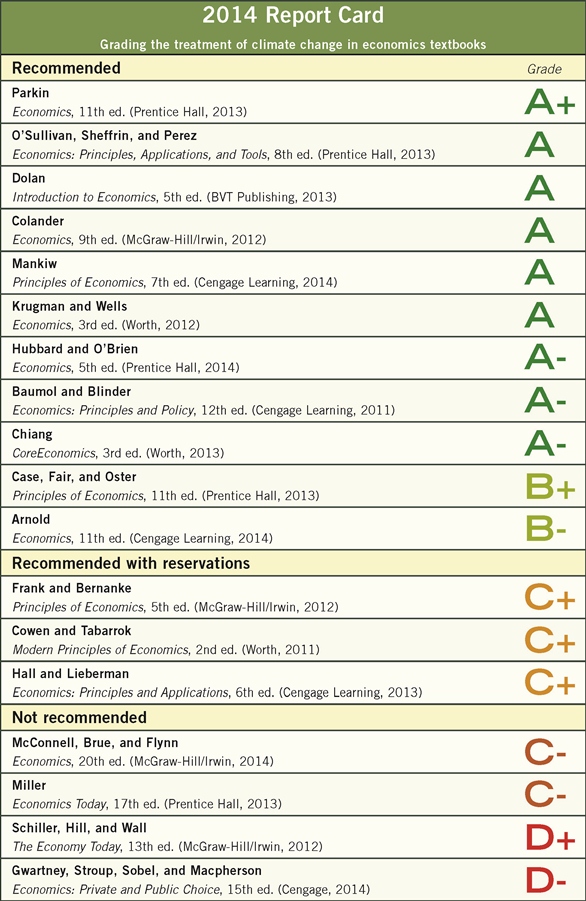

Without further ado, here is the full report, as well as our summary report card:

Comments are closed.