In July 2013, board members of the Central Puget Sound Regional Transit Authority, better known as Sound Transit, unanimously approved a pilot program to test several efficiency-boosting strategies for a woefully oversubscribed parking system. The pilot scheme was budgeted at $495,000 and set for a 2014 roll out, with three key measures:

- Parking permits;

- Real-time information on parking availability;

- Rideshare collaboration.

Unsurprisingly, the introduction of parking permits became the most controversial part of this new program. Following the announcement, Internet news forums were ablaze with furious commenters who questioned the logic of charging for what has always been a “free” good. Here’s a collection of the statements, ranging from frustrated, to angry, to apoplectic, and ending with a calmer voice:

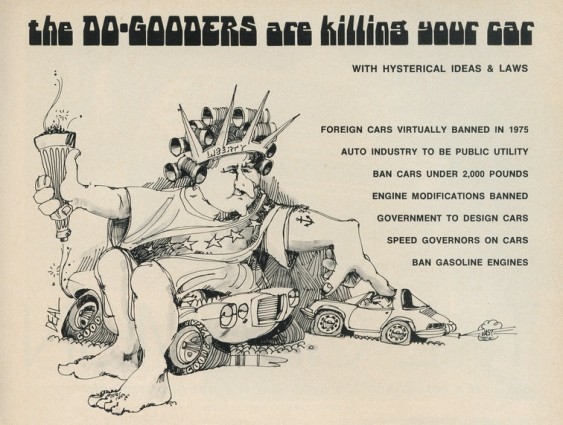

And the war on cars continues.

Great, so now only the rich can afford to take the bus too?

Forcing people to pay for a park-n-ride slot will backfire. These people are true idiots.

…idiotic idea. I’d actually do the unthinkable and vote for an Eyman initiative to stop Sound Transit if there was one.

Want ridership? Make the system easy to use. That means building parking lots. If you don’t want ridership, charge the users to park. Simple.

Some people think that free parking is mentioned in the Bill of Rights, right after cheap gasoline.

As alluded to in the final user comment, Hell hath no fury like a motorist deprived of free parking. The permit scheme ended on July 31st, and the early data supplied by Sound Transit suggests that the program was successful, raising the possibility that more fees may be coming to a transit center near you. Undoubtedly, the broader effect will be to alter long-held notions of the real cost of parking.

Background

The idea for the permit scheme originated from an April 2012 Sound Transit Board retreat. A key takeaway of the meeting was the need to optimize the use of existing parking lots. Park and ride usage data showed that many lots were close to capacity, and some had exceeded it. For instance, on Wednesdays of June 2014:

- 16 of 25 lots were over 80% full.

- 14 out of 25 lots were over 95% full.

- 3 lots were at 103%, 104%, and 132% capacity. (Numbers in excess of 100% were due to vehicles parking outside of marked areas.)

Numbers like this may be familiar to park and ride veterans, many of whom can conjure up memories of endlessly trolling an overstuffed parking lot, holding out hope for the sight of a tucked away, forgotten space. Obviously, that one hidden space needs to be located quickly before another driver steals it, and also before the arrival of the bus, because who wants to be late for work?

Parking Management Pilot

Sound Transit’s managers eventually stitched together several separate schemes into a single proposal, officially dubbed the Parking Management Pilot Project. And while the parking permits sparked the most controversy, the other two elements of the management plan — real-time data and ridesharing — deserve consideration as well.

The former, real-time parking information, was designed to make it easier for park and ride users to find a space. For a total of $273,000, the agency installed technology at four sites that allowed users to use mobile devices to find available spaces. The aim was to reduce the delays that park and ride users experience while cruising the lot looking for free spaces — which can be particularly frustrating when there are no open parking spots.

The latter, rideshare collaboration, did not involve a public-private partnership with Uber or Lyft, but rather the attempt at four transit centers to unite separate carpooling programs run by King County Metro, Pierce County Transit, and Snohomish County’s Community Transit. These programs are designed to increase the number of customers who carpool to transit centers, rather than drive their own vehicles. Getting a large number of transit users to regularly carpool to the park and ride, and then to take the bus, is Sound Transit’s preferred use for its facilities. This program was budgeted at $60,000. Finally, administration for the entire Parking Management Pilot was budgeted at $96,000.

Parking Permits

The parking permit scheme ran at four transit centers — Issaquah, Mukilteo, Sumner, and Tukwila — from February to July 31st. The Sound Transit website stressed that the pilot program did not mean that daily pricing was on the way, but instead provided people with assurance to find parking during the morning rush. However, this conflicted with public remarks from Sound Transit officials. “Our primary objective is to increase the number of transit passengers per parking stall,” said project manager Rachel Wilch to The Seattle Times. Also in The Times, it was reported that Sound Transit staff had originally drafted a proposal that called for a daily user fee for all spaces of $2 to $4, but ultimately rejected the idea.

As designed, a number of restrictions were set before one could obtain a permit:

- A valid ORCA card or U-Pass;

- In addition to possessing a transit pass, the user needed to have made at least 3 trips per week from the requested facility;

- Permits were priced at $33 per quarter for single users, and $5 for carpools;

- Permit spaces were available in blocked off areas on a first come basis, Monday to Friday, 6 AM to 10 AM. After that time the spaces were then open to all;

- The permit parking was located in the main parking area of each station, in spaces near the boarding platform. At Issaquah, for example, a purple block of paint delimited the permit section for carpools, and this section was nearest to the bus boarding area. A gold strip of paint blocked off the permit section for single users.

Permits: Space Type and #Sold

Location HOV #Sold SOV #Sold Remaining Spaces

Tukwila 8 5 123 141* 469

Mukilteo 3 1 12 11 48

Sumner 35 35 99 96 208

Issaquah 13 7 132 131 674

In nearly every case, the permits sold very well, essentially selling out at each station. Tukwila was a special case, as the number above shows that the permits sold at a level above the total available. Here, the full amount of permits sold out for the first quarter, but quite a few users did not renew for the second quarter. Sound Transit staff, relying on the collected utilization data, reduced the total number of stalls available for the second quarter and then sold more permits. The move worked, since no complaints were received from permit holders about their inability to find a space.

The decision by customers to renew or not to renew perplexed Sound Transit researchers. In some cases (Sound Transit did not detail specific renewal data) permit sales were robust for the first quarter, but then dropped slightly for the second quarter. According to customer feedback surveys, people chose not to renew for a variety of reasons: some didn’t take transit enough to justify the expense, while others found they were able to find “regular” spaces when they needed them.

Sound Transit officials told me that, overall, they regarded the permit scheme as a success. Permit sales were brisk and plenty of information was generated that in future will help the Sound Transit Board devise new ways of managing their parking supply.

What Sound Transit officials did not say is whether or not success will lead to the broader introduction of park and ride user fees. Yet to travel back to July 2013 when the scheme was being introduced, Sound Transit representatives were not shy in telling The Seattle Times that a successful pilot run might then lead to region-wide schemes, with fees possibly varying with demand for the parking spaces.

If the online reactions to the pilot program are any guide, expanding parking fees at park and rides would generate howls of protest from drivers who have grown accustomed to parking for free. Yet as we’ve said before, “free” parking is never truly free. Someone, somewhere, has to pay to build, maintain, and operate parking facilities.

One burning question is what to do with the revenue generated by parking fees. When one can’t find a space in a parking lot teeming with cars, the obvious answer for that driver is “Build more parking spaces!” Maybe. But the fees alone for such structures suggest that perhaps Sound Transit should have gone to a pay scheme years ago.

Consider two examples, past and present. The Issaquah Transit Center opened in July 2008, comprising 270,000 square feet and 819 spaces. For transit center design enthusiasts, it consists of a four-story concrete structure with a Green Screen exterior on two sides for climbing vegetation to grow through it, commissioned artwork, and Brazilian hardwood features on one side. At a price of $29.6 million, that breaks down to $36,141 per parking space.

For the future, Sound Transit is designing an elevated light rail station for Northgate, a neighborhood just north of Seattle, promising 14 minute downtown trips when the line opens in 2021. Current development plans call for 450 parking stalls at an average of $30,000, totaling roughly $13.5 million. Clearly, parking structures aren’t cheap.

So to return to the colorful user comments that opened this blog post — are park and ride user fees simply another full on barrage in the “war on cars”? Will these fees backfire and lead to a drop in ridership?

The somewhat fanciful notion of the “war on cars” has been dealt with elsewhere, so no need to spill further ink.

The question of a drop in ridership is an interesting one, however. In a way, it cuts to the very notion of why suburban motorists use the park and ride in the first place. Most often, the goal is to save on the cost and pains of driving oneself to a given spot in the big city. A bus rider will put up with the slow speed of the bus, its perpetually cramped quarters, and fellow passengers oblivious to any agreed norm of cell phone etiquette because, well, it definitely beats sitting in traffic.

But in a brave new world where park and ride user fees are the norm, these riders would likely pick up their own car keys only if the cost of mass transit rose exponentially, while driving fees stayed flat. Yet what’s likely to happen in future is an increase to the associated costs for both ways of traveling. Under this scenario, public transit ridership will probably not be affected.

To paraphrase another user comment, free parking and cheap gasoline were two rights omitted by the Founding Fathers at our nation’s birth. However, many motorists seem to think otherwise. But it is now certain that we are barreling towards a future where subsidies for car owners, such as free parking everywhere, are being slowly eliminated. Indeed, the absolute price for a car will likely be little changed, but the cost will certainly increase.

As the cost of car ownership rises, the rational consumer in all of us will emerge, and the resulting socio-behavioral changes will be wide-ranging. Instead of subsidies paid for by everyone in the community, those individuals who choose to drive will pay as they go along. We have noted the recent decline in vehicle miles traveled per person, a trend that shows little sign of abating. More will choose to carpool or use rideshares. Others will give up their car completely, instead opting to walk, bike, and use mass transit. At least these consumers will have a choice, rather than finding that they have no good transportation options besides the car.

The car—that former symbol of personal freedom—will not vanish from the streets of Cascadia any time soon. But the widespread adoption of user fees means that our communities no longer will be designed exclusively around their usage. And in the end, a future cityscape that is clean, easily and safely traversed, and where dense living is the norm, rather than an exception, might soon be a reality for all.

With thanks to Bruce Gray and Geoff Patrick at Sound Transit for supplying preliminary data and answering numerous questions. The complete Sound Transit report on the Parking Management Pilot Project is due in early 2015.

Comments are closed.