When a developer builds a family apartment in Vancouver BC’s downtown peninsula, the dining room comes with easy-to-clean floors that can handle spilled yogurt or spaghetti. Condo and rowhouse projects must have accessible stroller storage and outdoor play spaces, ideally where parents can look out a kitchen window and keep an eye on their kids.

As of Canada’s 2011 Census, downtown Vancouver’s urban neighborhoods were home to nearly five times more kids than Seattle’s and nearly 9 times more than Portland’s.

That’s in part because more than 20 years ago, Vancouver’s planners and politicians made a conscious choice: Not to relinquish the city’s urban core to empty nesters, low-income singles, and the childless.

As formerly industrial neighborhoods were converted to glass towers, Vancouver required at least 25 percent of that new housing to be suitable for families. That means at least two bedrooms, with attention to hundreds of details that make high-density housing function more like single-family homes. Where those zoning changes created enormous wealth, the city required private landowners developing the sites to incorporate parks, open space, daycares, libraries, community centers, elementary school sites, and other public amenities that families need.

In this post, I’ll outline Vancouver’s nearly unparalleled approach (at least in North America) to planning for families in dense, urban areas. In the next, I’ll look at how well those policies seem to be working for parents and kids in real life.

Since those policies went into effect in the early 1990s and tens of thousands of housing units were built downtown, families have repopulated Vancouver’s City Centre neighborhoods around False Creek, Coal Harbour, the West End, Yaletown, and other parts of downtown. Yes, it’s true that there are still fewer kids living in that urban core than in single-family neighborhoods that have historically had lots of kids. But the recent changes are what’s more interesting.

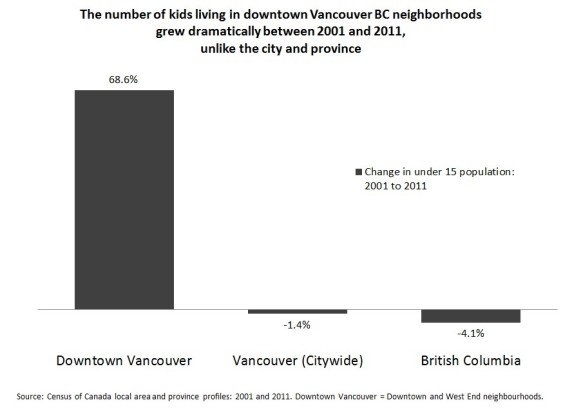

In 2011, downtown Vancouver neighborhoods housed more than 5100 children under the age of 15. (For comparison, downtown Seattle in 2010 had roughly 1100 kids that age and downtown Portland about 650.) The number of kids under 15 living in Vancouver’s downtown and West End neighborhoods has grown dramatically since 2001, with the largest increase in pre-school-aged kids. The city as a whole and the rest of British Columbia saw the number of kids under 15 decline over that same time period.

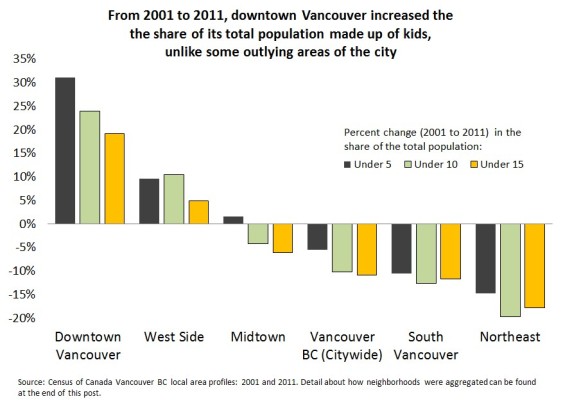

More remarkably, the share of Vancouver’s City Centre population that is made up of kids has actually increased. That’s unusual because aging baby boomers, longer life spans, and record low birth rates mean that the entire population is skewing older. Proportionally, there are simply fewer kids.

Except in places that have become magnets for families, like Seattle. As the chart below shows, only downtown Vancouver and West Side neighborhoods have been growing their shares of kids. Nearly everywhere else in the city, it’s shrinking. And the farther one gets from the center city, the share of kids tends to drop more precipitously. (More detail on how the neighborhoods were aggregated follows at the end of this post.)

‘It takes real leadership from the city’

Vancouver’s family-friendly policies aren’t perfect. Despite mandates to provide housing for low-income residents, affordability remains a huge issue. There’s still a frustrating shortage of daycare spaces and elementary school slots for downtown families. Some downtown parents say their condos or apartments work fine for little kids but won’t meet the needs of teenagers.

But without strong policies to at least create conditions where families can find a place in a city’s densest neighborhoods, it won’t just happen organically, argues Larry Beasley, Vancouver BC’s former chief planner who shepherded many of the policies that transformed the city’s urban core. As he put it:

This doesn’t happen unless a city takes real leadership to at least set it off to happen. The private market does not experiment that much. You may find the odd creative developer here and there, but in general they are building a standard product that they have a history of selling, whether that’s homes for empty nesters or studio apartments for singles. But after building those for years on end, the market goes flat because they’ve saturated the market for your typical high-density consumer.

If the local government establishes a policy and makes it clear that taking families’ needs into account is going to be required, developers may feel oppressed in the early years. But pretty soon they start discovering that market and seeing the broadening of the consumer base they’re appealing to. Then they come around, and innovative things start happening in the market.

Vancouver’s approach

So what did Vancouver do to attract families to its core? It made sure they could find suitable units by mandating that (typically) 25 percent of new high-density housing be designed for families. Vancouver introduced the concept in the downtown area, Beasley said, but it’s become standard practice in areas of the city that have been upzoned for medium- and high-density housing, including new development around transit stops.

To meet that requirement, units must have at least two bedrooms, large enough to fit a bed, dresser, desk or table, and some floor space for playing. That’s a huge step, because a downtown can have all the parks and museums and whimsical public art in the world, but without housing that’s large enough to meet their needs, families aren’t going to move there.

The city also recognized that many families don’t want to live on the 18th floor of a highrise tower, and encouraged a form of development with tall, skinny towers set atop a podium of townhouses or rowhouses that offer street-level residential entrances and multiple floors of living space.

Vancouver also created a 13-page manual, called “High-Density Housing for Families with Children Guidelines,” with rules of thumb that developers should follow when siting and designing the units. In the US, it’s hard to fathom the level of detail that Vancouver’s planners get into, so here’s a sampling of the guidelines:

- Bathrooms that are big enough to fit a parent and child.

- A non-carpeted entry area where parents can pull off wet jackets and muddy boots.

- No more than 12 units grouped together on the same hall or entry, to foster a sense of community.

- A minimum of 130 square meters of outdoor play space somewhere in the complex, ideally that parents can see from the unit, with separate areas for preschoolers and older children.

- Landscaping with non-toxic plants that can withstand the “rough and tumble of children’s play.”

- Soundproofing between units and sleeping areas that won’t be disturbed by proximity to living areas.

- In addition to clothes and linen closets, a minimum of 5.7 cubic meters of bulk storage space, within the unit or near the entry, that can hold strollers, wheeled toys, suitcases, sports equipment and holiday decorations

- Lockable bicycle storage adjacent to a building entrance.

And families appear to be colonizing these multifamily housing units at about the same rate as single-family homes. Ten percent of the rowhouses and duplexes built citywide from 2006 to 2011 have family households with children living in them, compared to 9 percent of the single-family homes and 8 percent of the units in buildings with five or more stories, according to a 2011 National Household Survey.

Vancouver planners also recognized early on that they couldn’t just rely on a “housing strategy” in dense urban areas. They also needed a “living strategy,” since what happened outside the walls of a home would be equally important to families.

So as the city rezoned areas to allow for more density, planners negotiated “Community Amenity Contributions” that required developers to build or even help fund the operations of daycares, parks, libraries, cultural facilities, service agencies, and community centers like Yaletown’s Roundhouse. In large redevelopment projects, developers also set aside sites for elementary schools.

Vancouver also typically requires that developers set aside discounted land so that 20 percent of new housing units could be affordable to low-income residents and families. The complicated “income mix zoning” policy requires the province and city to buy the land, and lack of public funding has been a barrier to building more affordable units.

Still, the non-market-rate “social housing” that has been built has been key to creating a critical mass of downtown families, Beasley said. In the market-rate units, a 3-bedroom apartment may be rented by roommates or a childless couple that wants elbow room. As Beasley explained:

One thing that we’ve heard that’s very important to urban families is evidence of other children. And the one thing that you can absolutely depend on is that if you build a social housing unit for families with children, it will have children in it because that’s the way the lists work. So they provide what you might call the core population of children. Kids don’t care if you’re rich or poor and it turns out that most urban families don’t either. So that social housing requirement is very important because those tend to be the pioneers.

As we’ll see in my next post, the reality on the ground doesn’t always live up to the policies. Some new developments haven’t exactly embraced the guidelines, and Vancouver’s school district has fallen behind in actually building elementary schools. Plus, the family-friendly guidelines themselves (adopted by the city council in 1992) could arguably use some updating.

But there are still lessons to learn from Vancouver’s experience. Yes, it’s true that Vancouver had the luxury of stronger land use planning authority, and of redeveloping huge swaths of industrial land adjacent to downtown, while other Northwest cities like Seattle and Portland generally don’t have such blank canvases to work with.

It’s also likely true that some of the growth in downtown families is simply because that’s where so many of the city’s new housing units have been built. And some advocates for urban density will undoubtedly argue that the kinds of requirements Vancouver imposed on development will lead to less housing being built overall.

But Vancouver’s demographics and healthy development history suggest that finding that balance can be done. And, at least from the perspective of one of the city’s most experienced planners, many American cities could be more aggressive in shaping the livable, inclusive, dense urban neighborhoods they profess to want. As Beasley put it:

I don’t buy the arguments that this is not possible in America. I’ve had a lot of conversations with American city counselors who say ‘Oh you’re all socialists up in Canada,” and I say to them, “You guys are the socialists. What you do in America way better than we do is subsidize development.”

Notes: City demographics were taken from the City of Vancouver’s Data Catalogue: Census 2001 Local Area Profiles and Census 2011 Local Area Profiles. The city’s 22 planning neighborhoods, found on this map, were aggregated as follows: Downtown Vancouver (downtown, West End); West Side (Arbutus Ridge, Dunbar-Southlands, Kerrisdale, Kitsilano, West Point Grey); Northeast (Grandview-Woodland, Hastings-Sunrise, Kensington-Cedar Cottage, Renfrew-Collingwood); Midtown (Fairview, Mount Pleasant, Riley Park, Shaughnessy, South Cambie, Strathcona); South Vancouver (Killarney, Marpole, Oakridge, Sunset, Victoria-Fraserview). “Downtown Eastside” is not an official planning area and is split between the downtown and Strathcona neighbohroods in the Census data.

BC demographics were taken from BC Stats Census of Canada 2001 British Columbia profile and 2011 Canada and the Provinces profile.

Statistics for children living in downtown Seattle come from the 2010 Census and include Uptown, South Lake Union, Belltown, Downtown, Pioneer Square, and Chinatown/International District (Census tracts 71, 72, 73, 80.01, 80.02, 81, 82, 91, 92). The analysis does not include Capitol Hill and First Hill neighborhoods sometimes included in downtown statistics. Downtown Portland figures include Census tracts 51—56.

Comments are closed.