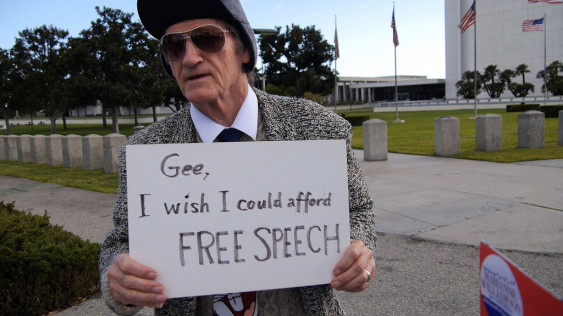

When the conservative majority of the US Supreme Court this week blew up the legal caps on the contributions the richest Americans can make to political parties and federal candidates, it was Citizens United redux: champions for those richest Americans gloated in newspeak about “free speech,” political reporters predicted even more private money flooding the air waves with attack ads, and reform leaders issued outraged statements. Most people, though, just shrugged, despondent but unsurprised, rolling their eyes in a giant, collective “what did you expect?” To most people, the whole system has long seemed rigged by the rich and powerful, and hope for reform is close to nil.

The vagaries of fate are such that the Northwest, especially Oregon and Washington and even more especially Seattle, are positioned to lead the national response to this latest travesty from the bench. They could do so both symbolically and practically, at the ballot box in both cases: by voting against the court’s ruling and then by creating a whole new way of paying for campaigns.

Wrecking Crew

The McCutcheon decision extended the money-is-speech-and-speech-is-sacred logic of Citizens United, and the Court majority gave no indication it is done using that logic to demolish campaign finance regulations. Eventually, the majority may smash others too: the ban on direct gifts from corporations to candidates, for example, and the limit on how much you can give to an individual pol.

Already, the Court’s wrecking crew has made these restraints largely irrelevant. Thanks to Citizens United, anyone, including a corporation, can spend unlimited sums, anonymously, on spuriously named “independent expenditure campaigns.” McCutcheon opens the door to a scam that eviscerates the direct-gift cap: candidates can solicit multi-million dollar gifts for their “joint campaign funds,” then parcel out the proceeds to members of their caucus. Those caucus members can reciprocate, tit for tat. Presto! Each candidate ends up with as much money as she or he raised from each billionaire. (In his vehemently dissenting opinion, Justice Breyer spelled out several other ways that candidates can waltz right past the individual gift limit, thanks to the majority’s see-no-evil ruling.)

Few Supreme Court decisions lodge in public consciousness the way Citizens United has. It’s entered the ranks of rulings, like Roe v. Wade, that many Americans can name unprompted. In recent focus groups among voters in Washington State, for example, participants brought up Citizens United again and again as a quintessential example of what’s wrong with American government. Citizens United is so well known that McCutcheon is likely to simply be known as its sequel, and it’s likely to be abhorred.

People of all political stripes loathe Citizens United. Nationwide in the United States, in 2010, four in five people—76 percent of Republicans, 81 percent of independents, and 85 percent of Democrats—opposed it. Opinion has remained just as negative ever since. The super-PACs and “social welfare organizations” and barrages of attack ads that Citizens United unleashed are sickening to most voters; they reinforce Americans’ impression that government is bought and paid for.

Yet if Citizens United and McCutcheon are big parts of the problem, fixing them the normal way may not be the solution. At least, fixing these Supreme Court rulings may be the long way around the block—the extremely long way. The normal path is to amend the US Constitution. A much shorter path is open, and it’s a path that leads right through Cascadia’s principal city. The question is, can the united revulsion against these rulings fuel a political movement that is smart and strategic—a movement in which each step forward is possible and practical and makes the subsequent steps that much easier, and that leads to a democracy uncorrupted by the influence of private, moneyed interests?

Move to Amend

Don’t get me wrong. I would be eager to amend the constitution, to make clear that corporations are economic constructs, purely subservient to natural human beings in political rights and that political spending is, while relevant to freedom of speech, something that lawmakers are welcome to regulate to prevent the wholesale corruption and perversion of democracy that is so readily apparent in the United States today.

Northwesterners’ first opportunities to lead the national response to McCutcheon is to encourage such an amendment. Oregon’s state legislature recently came close to passing a resolution calling on Congress to begin the amendment process. Reformers in Washington are gathering signatures on a citizens’ initiative to do the same. I’ve signed it and passed it around: Initiative 1329.

Most Americans wholeheartedly agree with the sentiment of these reforms.

In fact, on April 1, the day before SCOTUS handed down McCutcheon, some 13 Wisconsin cities and 48 Maine communities joined the more than 150 other jurisdictions that have passed resolutions calling on legislatures and Congress to amend the constitution and overturn Citizens United. In Cascadia, in 2012, such initiatives won huge victory margins in the cities of Arcata, California; Ashland, Corvallis, and Eugene, Oregon; in Mendocino County, California, and Lincoln County, Oregon; and in the state of Montana. In fact, every single time and place that an anti-Citizens United measure has been on a ballot anywhere in the United States, voters have approved it, usually by lopsided numbers. In Montana, it won three to one.

The problem is, what then? Amending the US Constitution is nearly impossible. It requires votes of two-thirds of each house of Congress plus ratification by three-fourths (38) of the 50 states. The US Constitution, the oldest written constitution in use worldwide, is notoriously hard to amend. (It’s rarely emulated anymore by new democracies and constitution reformers elsewhere.)

Voters may hate Citizens United, but members of Congress do not—anyway, most members do not. They are, after all, the Americans who have won office in the political environment it spawned; they’re the last people you’d expect to want to change it. Thus, overturning it through a constitutional amendment is unlikely to happen anytime soon. In the meantime, a Supreme Court with a more nuanced understanding of real-world politics could reverse it. That is, in fact, a more-likely scenario over the next decade. The blistering intensity of the dissenting opinion published by the four moderate justices in McCutcheon shows how closely divided the court is. The court’s composition will shift over time, possibly in a direction friendlier to political reform.

Move the Food

But the difficulty of amending the constitution is not the main reason to understand the amendment strategy as primarily a symbolic, grassroots-mobilizing effort. The main reason is hydraulic. “The history of campaign finance reform,” writes law professor Lawrence Lessig in his influential book Republic Lost (page 270), “is water running down a hill. No matter how you reform, the water seems to find its way around the obstacle.” No sooner do you restrict gifts to candidates but “soft money” to parties gushes. Dam that, and the money flows through lobbyist-“bundlers.” Caps on gifts gave rise to independent expenditures. PACs gave birth to super-PACs. For every obstacle reformers erect, political fundraisers devise increasingly nefarious schemes to circumvent them. Political money, like water under pressure, leaks.

A better strategy is to provide a different source of political money—one that is easier for candidates to collect in quantity and that is divorced from political patronage. Put another way, rather than trying to herd cats away from the food supply, we should move the food. There’s more to this analysis than I can articulate here, so I’ll return to it another day, but the outlines and conclusions are clear.

Professor Lessig again, from his e-book Lesterland:

The analytics are easy: We solve this corruption not by “getting money out of politics,” not by declaring that “money is not speech,” not … by declaring that “corporations are not persons”…. We solve this problem by embracing “citizen-funded elections.” By adopting a system, in other words, that: (a) demands less candidate time raising money, and enables candidates to raise that money from (b) a wider slice of America. Such a system of “citizen-funded elections” would not require a constitutional amendment, or at least not at first. Even this Supreme Court has clearly affirmed the power of Congress to complement the system for funding elections in a way that would effectively spread the influence of the funders to the people generally.

What is required is that first cities, then states, and ultimately the federal government begin making available to all citizens small allotments of public money to give to candidates and parties of their choice. They can use tax credits, matching funds, or per-capita Democracy Vouchers. All citizens can then make small political contributions—say, up to $100 per election. To receive these publicly supported contributions, however, candidates would need to abide by the rules of citizen-funded elections: mainly, they would need to stop raising (much) money from other sources.

Just $100 per citizen—rebated from tax bills, to give to the candidates of your choice—may not sound like enough money to counteract the corrupting flood of Koch cash. But do the math. Assume, for simplicity, that just 200 million people (out of 317 million) in the United States would receive $100 Democracy Vouchers to donate to the candidates of their choice. That’s $20 billion. In the 2012 election cycle, the most riotous orgy of political spending ever seen on planet Earth, all the money used on all federal US races—including “dark money” and super-PACs and independent expenditures and political parties and candidates’ own war chests—was about $7 billion. Democracy Vouchers would have dwarfed private money, and if you were running for office, that would change everything about your campaign. More: it would change the entire dynamic of politics, as I’ll discuss in another article.

And now the good news: Cascadia has a chance to lead. Reformers across the United States are looking for opportunities to expand citizen-funded elections from Connecticut, the city of New York, and the few other jurisdictions that already have them. They are eager to build momentum toward national reform, following the state-by-state pattern of the marriage equality movement. Perhaps the best opportunity anywhere in the United States this year is in Seattle.

Last year, voters in the city considered a citizen-funded election system for city council races, modeled on New York City’s best-in-class system: a voluntary program in which qualifying candidates for city council receive multiple matches for small-donor gifts. The formula for matching gifts has, in New York, dramatically reduced how much time candidates spend fundraising and boosted how much they spend discussing issues with constituents. It also radically democratized the rolls of donors, spreading them across the city and its different communities. Candidates no longer spend their days sucking up to the richest citizens, because political money is spread evenly across the city. Talking to lots and lots of voters is the best way to raise money in New York, as it will be in Seattle under a citizen-funded election regime.

The Seattle measure was a sleeper: little known or understood. It did not arise out of any scandal or grassroots mobilization. Instead, a change in state law allowed conscientious city council members to revive citizen-funded campaigns as a good government measure. The city had a similar system two decades ago that a state initiative destroyed. Voter and media attention were distracted by a well-funded and ultimately successful campaign to convert most city council seats from at-large to district elections. Consequently, Seattle’s citizen-funded election measure trailed badly in the polls at first, and it had only a meager, ragtag campaign behind it—a campaign of scrappy volunteers and a budget for exactly zero advertising in any medium. Yet despite odds stacked against the measure, voters came within a fraction of a percent of passing it. The mailing of even one batch of flyers to certain precincts probably would have provided the victory margin.

The Seattle city council has the opportunity to lead by placing the proposal before voters again this fall. The prospects for success are excellent. This spring, a robust and organized campaign is already in the works. A likely vote on raising the city minimum wage will bring voters to the polls in large numbers. And national political reform organizations are likely to help. A victory in Seattle would throw sparks far and wide. It might inspire revival of Portland’s citizen-funded (but somewhat badly designed) election system, which voters there discontinued some years ago. It might also lead to emulation in other cities and, perhaps, at the state level in Oregon or Washington.

Fate has handed Seattle a rare chance. Will the city council lead the national response to McCutcheon, Citizens United, and the whole sorry scene of politics drenched in the corruption of big money? If it does, this week’s news from the wrecking crew on the Supreme Court could be the beginning of a turnaround for American self-government.

Comments are closed.