Here’s a Rorschach test. I’ll show you a word. You say the first thing that comes to mind.

The word is “government.”

Stop. Go down to comments and record your reaction.

Now, I’ll tell you what your answer means about you. If you’re like many of the friends I’ve asked, your answer is not typical. They said things like “protects,” “services,” “rule of law,” and “us.”

If you’re more normal, you said something less flattering. The most common answer among Americans is a derisive laugh. Yep. A laugh. The G-word qualifies as a one-word joke. Other common answers include snorts of disdain and words like “corrupt” and “waste.” One friend said “sociopaths”; another, amusingly, said “statues.”

Political analyst Andrew Levison, who works for the Democratic Strategist, summarizes in one sentence a recent set of public-opinion studies concerning attitudes toward government: “The level of anger, cynicism and disgust is almost impossible to overstate.”

In fact, in-depth, anthropology-style research shows that Americans have only a faint, faded concept of “government” that doesn’t implicitly mean “bickering politicians” or “wasteful bureaucracy.” A FrameWorks Institute messaging memo, distilling a massive opinion research project on how campaigners should talk G-word, makes the point plainly:

The word “government” poses an obstacle to productive thinking. The word “government” is so freighted with pejorative baggage that it should be used with caution and is best used only after other terms that establish its public mission. Without this redirection, government is universally greeted with derision—and that response is socially expected across Democrats, Republicans and Independents. Deep-seated ridicule, learned and conditioned over time, remains a major impediment to engaging citizens in a discussion about government as us, and government as problem-solver. If government is allowed to be identified as a “joke,” the rest of the conversation hardly matters.

Distrust

Distrust of government is among the most fundamental challenges for creating a sustainable Northwest. We need government to solve our biggest problems, but most people actively distrust government.

Every one of the reports I’ve read on public opinion polls and focus groups concerning tax shifting over the years since writing a book on the subject in 1998, for example, has indicated that citizens do not believe government will actually offset new carbon revenue with tax cuts. They support tax shifting in principle, but in practice, they are sure the government will screw them over. Even in British Columbia, where trust in government is more robust than in the Northwest states, and where the six-year-old carbon tax shift is demonstrably revenue neutral, many citizens still do not believe it. They are sure that it is somehow a tax grab.

Public support for carbon cap-and-trade proposals are similarly sand-bagged by voters’ conviction that politicians will set up carbon markets in ways that allow their donor-sponsors to extract ill-gotten profits. Carbon markets, many citizens believe, will become as rife with fraud as were mortgage-backed securities in 2007; all arguments to the contrary seem to bounce off this conviction.

In 2010, when Washington voters overwhelmingly rejected a ballot measure that would have taxed the income of the richest households in the state to fund education and health services, polling showed that the proposition never had a chance. Middle-class voters—whose children would have attended better-funded schools and, by law, never paid the tax—were certain that legislators would quickly extend it to them. No number of assurances could sway them.

More generally, citizens across North America share values and aspirations that are fairly progressive. They want cleaner air and water, a stronger social safety net, conservation of our natural heritage, better schools and transit and a safer food supply. They even indicate a willingness to pay for such things. But they are sure politicians and government institutions cannot be trusted to deliver them. In their values, they lean left; on the question of government performance, they are right wingers.

Thus, we are in a Catch-22: We cannot fix our big problems—opportunity for all, climate change, wholesale upgrades for infrastructure and education—without collective action. But we do not trust our government, the vehicle for collective action. Consequently, we cannot fix our problems. Veteran pollster and strategist Stanley Greenberg underlines this conclusion, arguing that progressives “will not make sustainable gains unless they are able to restore the public’s confidence in its capacity to act through government.”

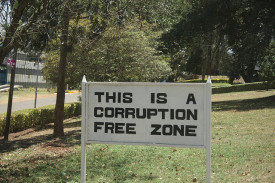

Corruption

The reasons for the lack of trust are several and hotly debated, but important among them is the widespread perception that government is thoroughly corrupt, that politicians are bought and paid for. Andrew Levison, in a review of the political attitudes of working class Americans, writes that they believe, “politics has become the business of selling votes and influence in return for either campaign contributions, a high-paying job or ‘under the table’ bribes.”

Such beliefs have become typical. William Galston of the Brookings Institution reports that, “In 1964, . . . 64 percent of Americans thought the government was being run ‘for the benefit of all the people’ compared to only 29 percent who thought it was being run by and on behalf of ‘a few big interests.’ Ten years later, those percentages were reversed: only 25 percent said it was operating for the benefit of all, versus 66 percent for the big interests. And with some ups and downs, that is about how sentiment has divided ever since.”

In North America, the amount of actual, law-breaking, vote-buying, quid pro quo corruption—corporate fixers handing sacks of cash to politicians in back alleys—is minimal. But voters are basically right that the political system is thoroughly corrupt. Politicians do not sell their votes, but they represent the views of their donors, and donors are mostly rich.

This subtler form of corruption, what Harvard Law Professor and democracy crusader Lawrence Lessig calls “systemic corruption,” is ubiquitous. (Lessig’s book, e-book, TED talk, and new four-minute video and are the best introductions to the topic of money in politics, bar none.) Systemic corruption allows participants in the political process to feel virtuous and law-abiding, yet it perfectly perverts representative democracy. Elected representatives speak not for the views of the majority of their constituents but for their contributors. Political scientists Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson summarize some of the vast academic literature in their classic analysis of the politics of economic inequality Winner-Take-All Politics:

[Political scientist Larry] Bartels looked at how closely aligned with voters U.S. senators were on key votes in the late 1980s and early 1990s. It turns out there is a pretty high degree of congruence between senators’ positions and the opinions of their constituents—at least when those constituents are in the top third of the income distribution. For constituents in the middle third of the income distribution, the correspondence is much weaker, and for those in the bottom third, it is actually negative. (Yes, when the poorest people in a state support a policy, their senators are less likely to vote for it.)

. . . In a truly mammoth research undertaking, [Political scientist Martin Gilens] collected almost two thousand survey questions fielded since the early 1980s that ask people to say whether they wanted government policy to change. Then he looked at whether government policy actually did change. Like Bartels, Gilens did not just look at people in general, but broke the population down into income groups. Did it make a difference, Gilens asked, whether a policy had strong support among the poor . . . , the middle class . . . , or the well-off . . . ?

It turns out it makes a huge difference. Most policy changes with majority support didn’t become law . . . . But they only stood a good chance of becoming law, Gilens found, when they were supported by those at the top. When the opinions of the poor diverged from those of the well-off, the opinions of the poor ceased to have any apparent influence: If 90 percent of poor Americans supported a policy change, it was no more likely to happen than if 10 percent did. By contrast, when more of the well-off supported a change, it was substantially more likely to happen.

But what about the middle class? They did not fare much better than the poor when their opinions departed from those of the well-off. When well-off people strongly supported a policy change, it had almost three times the chance of becoming law as when they strongly opposed it. When median-income people strongly supported a policy change, it had hardly any greater chance of becoming law than when they strongly opposed it. As Gilens concluded acerbically, “Most middle-income Americans think that public officials do not care much about the preferences of ‘people like me.’ Sadly, the results presented above suggest they may be right. Whether or not elected officials and other decision makers ‘care’ about middle-class Americans, influence over actual policy outcomes appears to be reserved almost exclusively for those at the top of the income distribution.”

These and other academic studies confirm the public perception of corruption. What American democracy looks like has a name. It is plutocracy, rule by the rich. And that rule has only intensified since the studies were completed; after all, they date from before Super-PACs and “dark money” turbocharged the influence of private interests.

In the new world of Citizens United, where winning a seat in the US Senate can cost tens of millions of dollars, where a presidential run costs a billion dollars, where Big Ag can spend $22 million in one state to defeat a milquetoast measure that simply required food products to indicate whether they contained genetically engineered ingredients, and where billionaires spend without limits on spurious smears against candidates they dislike—in this strange new world, this ugly perversion of democracy, why should anyone trust government? Isn’t distrust the only appropriate reaction? Maybe “the level of anger, cynicism and disgust is almost impossible to overstate” because people have been, you know, paying attention.

Democracy

None of which is to say that the problem of distrust is insoluble. It’s just that to solve it, we not only have to talk differently about the G-word, we have to make government trustworthy. We have to reclaim it.

This article launches a new series about how to do that, mostly by overhauling how we pay for campaigns, but also by making money matter less in those campaigns, by expanding voting, and perhaps by rewriting some of the rules by which elections operate.

The crux of the whole solution, however, according to Andrew Levison of Democratic Strategist,

is a political process that is entirely funded by small donations from ordinary citizens rather than large contributions from corporations and other special interests. The basic rule of thumb is simple—a politician should not be allowed to accept any sum of money that is large enough to influence his vote. He or she should be financed by hundreds or thousands of small contributors, none of whom can or will expect any special favors in return for their support.

The path to restoring a modicum of trust in government—a likely prerequisite to victory on big challenges like climate change and economic inequality—leads through political reform.

We have to take government back from the private interests that are currently calling the shots. We have to reclaim the g-word. We have to make it no longer a joke. We have to make it look like democracy.

Comments are closed.