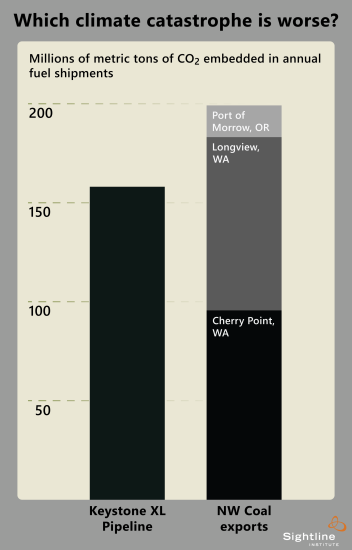

Back by popular demand, here’s a look at the carbon dimensions of two climate change horror shows in the making: the Keystone XL Pipeline and new coal export terminals in the Northwest. From the “King Kong versus Godzilla” files, here’s my analysis of their carbon impacts.

The result surprised me: coal exports look to be an even bigger climate disaster than the pipeline. We can ill afford either one of these projects, but until we have a clear energy policy that respects climate science we’ll be wrestling with these kind of deadly proposals one at a time.

Now, for geeks out there, here’s the methodology I used to generate these numbers.

To calculate the carbon dioxide emissions from coal exports, I assumed that 100 million metric tons of Powder River Basin coal are exported each year. (That’s just the sum of the 48 million tons planned for Cherry Point, Washington; 44 million tons planned for Longview, Washington; and 8 million tons planned for the Port of Morrow, Oregon.) Then I estimated that each ton of coal would produce nearly 2 tons of CO2, on average, a figure that is consistent with data published by the US Energy Information Administration, which reports that burning subbituminous coal results in emissions of 97.2 kilograms of CO2 per million BTUs. Assuming that export-grade US coal contains 9,300 BTUs per pound, each metric ton would produce 1.99 tons of CO2, on average. (Incidentally, Environment Canada reports carbon intensities for western Canadian subbituminous and other forms of coal; those figures are similar.)

Given my assumptions, the math is straightforward and yields an estimated 199 million metric tons of CO2 from export coal on an annual basis. My coal emissions accounting leaves out a lot. I did not count the emissions associated with mining, processing, rail shipping, storing, maritime shipping, constructing new port or rail facilities, or any other related activities. I also didn’t count any non-CO2 or fugitive emissions. All I counted, in short, was the CO2 that will be directly released by burning the coal.

To estimate the CO2 emissions from oil moving via the Keystone XL pipeline, I assumed that the pipeline moves 830,000 barrels of oil per day (about 303 million barrels per year), which is what the US State Department says, and that it would transport mostly bitumen derived from oil sands. When burned, each barrel of bitumen releases an average of 0.521 metric tons of CO2; see Table 1 of the report, “The Carbon Contained in Global Oils,” by Deborah Gordon of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. (Note, however, some technical details that make my estimates uncertain to a degree. For example, the pipeline may transport fuels produced from a range of different sites, and that the carbon content of different bitumen products may vary. Also note that estimates of carbon intensity of bitumen fuels vary; see, for example, Table 1 of the NRDC report, “GHG Emission Factors for High Carbon Intensity Crude Oils.” What’s more, my estimates do not account for diluents, which are hydrocarbons that are processed and/or transported before being blended with pure bitumen for pipeline transport, although the US State Department concludes that diluted bitumen is only 6 percent less carbon intense than pure bitumen on a “well-to-wheels” basis; see Appendix W of its initial assessment of the Keystone XL pipeline.)

Crunch the numbers and you wind up with an estimated 158 million metric tons of CO2 for oil moved in the pipeline. As with coal, my estimates do not account for the additional emissions associated with bitumen extraction, upgrading, processing, transporting, handling, or refining. Nor do they include the emissions from coal-fired power plants’ combustion of low-price petroleum coke, which is derived from bitumen refining and upgrading; see OilChange International’s report, “Petroleum Coke: The Coal Hiding in the Tar Sands.”

I cross-checked my figures with the State Department’s greenhouse gas estimates in Chapter 4 (page 4.14-4 and following) of the Keystone XL’s recently-released Environmental Impact Statement. State estimates that on a “lifecycle basis”—that is, including production and refining, as well as combustion—the pipeline’s oil would result in emissions of 147 to 168 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent.

To maintain a roughly apples-to-apples comparison between my coal and oil calculations, I did not factor in emissions from shipping, refining, distributing, constructing infrastructure, or any other related activities. And again, I didn’t count any non-CO2 or fugitive emissions. All I counted, in short, was the CO2 that will be directly released by burning the coal and oil. Comments and suggestions (and corrections) are very welcome.

A big thanks to Goodmeasures.biz for graphic design work on the chart.

Comments are closed.