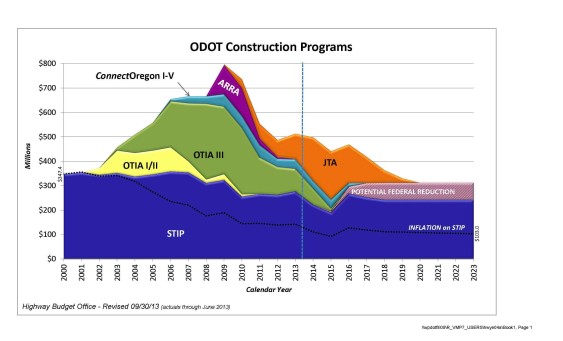

The Oregon Department of Transportation recently admitted that, after going on a construction spending spree in the 2000s, it is now going broke. This chart does a pretty good job of displaying the collapse in the agency’s construction budget:

At this point, virtually all of the agency’s revenues are committed to debt service and basic road maintenance. There’s almost no money left for new construction.

One of the chief causes for the revenue shortfalls: in the state’s words, “People are driving less.”

Here’s what the agency has to say about recent driving trends:

For six decades after World War II an expanding economy increased the average miles driven per person virtually every year. But in recent years the regular increase in vehicle miles traveled (VMT) has stopped, and VMT growth has slowed or gone negative. While debate about the causes of this continues, research indicates that demographic trends—including Baby Boomers retiring and less driving by the younger generation—has reduced the link between VMT and economic growth.

I count this sort of honesty as a rare treat. I mean think about it: Oregon’s transportation officials now admit that, even after a decade of massive highway spending, demand for all of that new road capacity is evaporating!

And I have to give ODOT even more credit for acknowledging other structural problems with the transportation budget, including…

- “Construction cost increases over the past decade: “Construction costs more than doubled between 2001 and 2008.” Wow!

- The “Lack adequate and dedicated funding for non-highway modes” that has kept funding for non-highway modes “episodic.” (That’s transportation-speak for “Flaky and meager.”)

- Debt service: “In 2001 the OTIA program authorized ODOT to use bonding for highway projects for the first time…And while ODOT is paying off that debt, the state will have a lot less money to spend on new projects.”

Yet it seems that ODOT’s leadership has learned little from its lost decade, and remains committed to massive, debt-fueled highway expansions. Exhibit A: the agency is still trying to reanimate the corpse of the Columbia River Crossing—which would double the number of lanes across the river—despite growing evidence that tolls would divert much of the traffic to another bridge, making much of the added capacity superfluous.

By pursuing the CRC, ODOT is doubling down on the strategy that has already landed the agency in its current funding mess.

Maybe ODOT’s leadership has a long-term agenda with its support for the CRC: bringing the state’s transportation budget crisis to a head, in order to build political momentum for a massive new highway funding package. Yet if Washington’s experience is any guide, this strategy could prove to be a dud. WSDOT’s budget has many of the same woes as ODOT’s; but despite agreeing on the basic contours of a lopsided, road-heavy transportation package, the Washington House and Senate quibbled about details, and the legislation foundered.

But even if the Oregon legislature could avoid that political quagmire, there’s every reason to believe that reviving the highway spending spree of the 2000s would just land the state right back where it is now: broke, with flat or declining traffic, not enough money for road and street maintenance, and critical shortfalls in funding for the transportation modes that are actually on the rise: transit, biking, and walking.

All of this makes ODOT’s brutal honesty a little less refreshing. After all, what good is self-awareness if it doesn’t change what you do?

Comments are closed.