Oil and coal companies hope to dispatch scores of trains across the Northwest each day, bearing fuel to refineries and port terminals. To help the public understand the magnitude of these schemes, Sightline is highlighting key rail crossings from Sandpoint, Idaho, to Cherry Point, Washington, along the main path the trains would take from the interior to the coast.

In this installment we examine communities in Snohomish County, Washington.

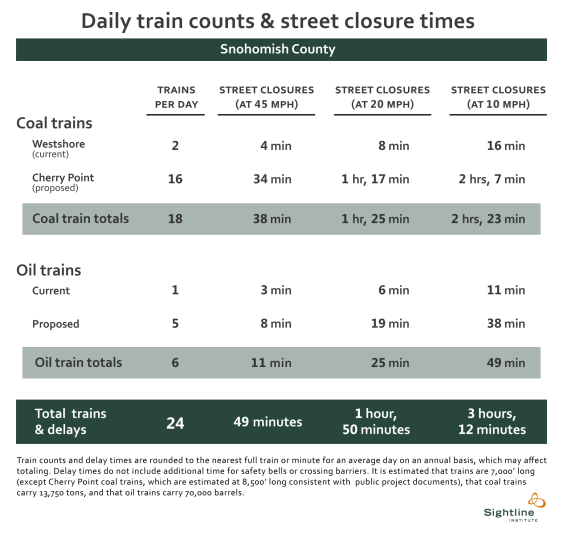

So massive are the fossil fuel industry’s plans that simple math shows that the shipments would close streets for hours each day as trains pass through at-grade crossings.

In Snohomish County, we estimate that coal and oil trains would close streets by an average of between 49 minutes and 1 hour and 50 minutes, each day. At the slower speeds that are typical of urban areas, fossil fuel trains could shut down streets for more than 3 hours every day. That’s over and above current street closures from trains.

In Snohomish County, we estimate that coal and oil trains would close streets by an average of between 49 minutes and 1 hour and 50 minutes, each day. At the slower speeds that are typical of urban areas, fossil fuel trains could shut down streets for more than 3 hours every day. That’s over and above current street closures from trains.

Please note that our analysis is not a complete account of street closures, but rather a set of examples of public at-grade crossings that would be impacted by coal and oil trains.

In our last installment, we examined street-rail interfaces in King County from Auburn to Seattle. In this chapter we look at the next leg of the journey as trains continue along Puget Sound to reach Snohomish County and the town of Edmonds.

Edmonds, WA: Dayton Street and Main Street

Edmonds has two BNSF public grade crossings that separate the town from the waterfront. Each sees approximately 38 trains daily. Dayton Street, which provides access to the marina, boardwalk, and restaurants handles 8,500 vehicles on an average day. But the Main Street crossing is likely to be more problematic because it provides the sole access to the ferry terminal where boats connect Edmonds to the town of Kingston on the Kitsap Peninsula. With 26 daily departures in the winter, the Edmonds ferry dock is an important link in the region’s transportation system. All vehicles leaving or entering ferries must transit the Main Street crossing.

A study of Edmonds by Gibson Traffic Consultants provides more detailed analysis of potential impacts. (Additional study attachments here.)

Further north, trains reach another ferry terminal city, Mukilteo.

Mukilteo, WA: Mt. Baker Avenue

Mukilteo’s ferry terminal access is not impacted by trains because a bridge spans the tracks. The only street in town likely to be directly impacted from increasing train volumes is Mt. Baker Avenue, an extension of Mukilteo Lane, that handles 322 vehicles daily. It is protected by gates. The popular Mukilteo Lighthouse Park, is located adjacent to the railway; it is indicated by tree icons west of the ferry dock.

Continuing north, coal and oil trains arrive in Everett.

Everett, WA: 23rd Steet

Everett, WA: 23rd Steet

The city of Everett is home to a major railyard as well as public at-grade crossings such as 23rd Street along the industrial portion of the waterfront. Flashing lights warn vehicles about train traffic on the four tracks along which 44 trains pass daily. Street traffic is light at 420 average daily vehicles. The “children crossing” icon to the southeast marks Everett High School.

After trains leave Everett, they cross the Snohomish River and a wetland area of meandering sloughs before coming to Marysville.

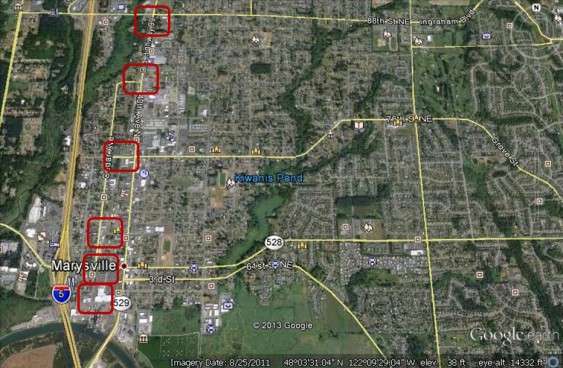

Marysville, WA: 1st Street, 4th Street, 8th Street, Grove Street, 80th Street, and 88th Street

Marysville, WA: 1st Street, 4th Street, 8th Street, Grove Street, 80th Street, and 88th Street

The town of Marysville is arguably the community most likely to be adversely impacted by increased coal and oil trains. Current rail traffic is just 15 trains daily, but the town lies along the route to the planned coal terminal at Cherry Point, as well as four refineries that aim to receive oil trains, projects that would put an addition 21 or so trains on the rails each day. In other words, current proposals would more than double the number of trains passing through in Marysville, and the trains would be longer than most current trains seen in town.

Street traffic is highest at 4th Street and 88th Street, where more than 28,000 vehicles cross the tracks on an average day on each street. Not only are Marysville’s downtown streets very busy, but the area is small enough that Gibson Traffic Consultants points to a potential “nightmare scenario” where all of the city’s access points to Interstate 5 are obstructed simultaneously.

Several “children crossing” icons represent local schools, including Allen Creek Elementary School just north of State Route 528 and Marysville Middle School near the Kiwanis Pond label. East of the 88th Street crossing one sees, in order, Pinewood Elementary School, Cedarcrest Middle School, Grace Academy, and Marysville Getchell High School. The book icon near 76th Street marks the Marysville Library.

The street disruptions continue north of central Marysville.

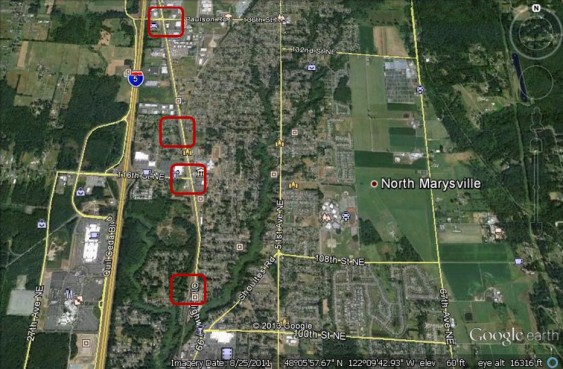

North Marysville, WA: 104th Street NE, 116th Street NE, 122nd Street NE, and 136 Street NE

North Marysville, WA: 104th Street NE, 116th Street NE, 122nd Street NE, and 136 Street NE

Each of the crossings here is protected by gates with the highest street traffic volumes at 116th Street NE, where 20,400 vehicles cross the tracks on a typical day. The Tulalip Resort Casino lies to the west of the 104th Street crossing. To the east of the 116th Street crossing, a “children crossing” icon marks Marysville-Pilchuck High School. To the east of the 136th Street crossing, a mortarboard marks Columbia College, and another “children crossing” icon marks Shoultes Elementary School.

Northbound trains head into the rural area around the town of Stanwood.

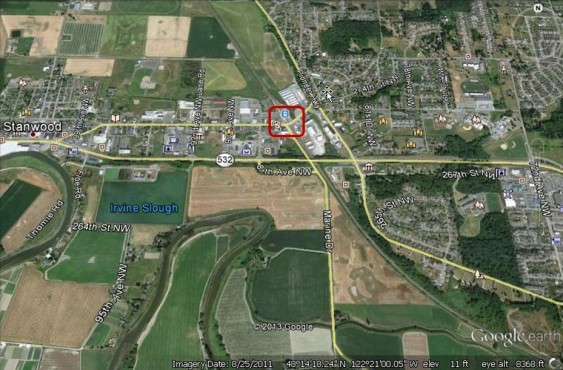

Stanwood, WA: 271st Street NW

As in Marysville, new coal and oil proposals would more than double existing train traffic through Stanwood. Currently, 15 trains a day pass through the 271st NW crossing where 6,900 vehicles traverse the rails. To the west of the rail crossing, the “children crossing” icon marks Stanwood Elementary School, and the book icon marks the Stanwood Library. To the east, “children crossing” icons mark Lincoln Hill High School and Stanwood High School. Southeast of the tracks, a “child crossing” icon marks Port Susan Middle School. (Gibson Traffic Consultants has also studied the impact of new trains in Stanwood.)

In our next installment, we will follow fuel trains as they continue north into Skagit County en route to oil refineries or coal terminals.

You can enlarge the images by clicking on them.

Click here for notes, sources, and methodology.

John Abbotts is a former Sightline research consultant who occasionally submits material that Sightline staff turn into blog posts. Thanks to Devin Porter of Goodmeasures.biz for designing the table.

Have photos of a crossing featured in this series? Share them in our “Wrong Side of the Tracks” Flickr pool.

Comments are closed.