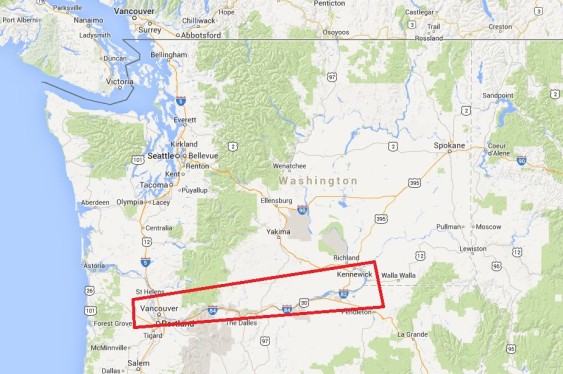

Oil and coal companies hope to dispatch scores of trains across the Northwest each day, bearing fuel to refineries and port terminals. To help the public understand the magnitude of these schemes, Sightline is highlighting key rail crossings from Sandpoint, Idaho to Cherry Point, Washington along the main path the trains would take from the interior to the coast.

In this installment we examine communities along the Columbia River from Benton County to Vancouver, Washington.

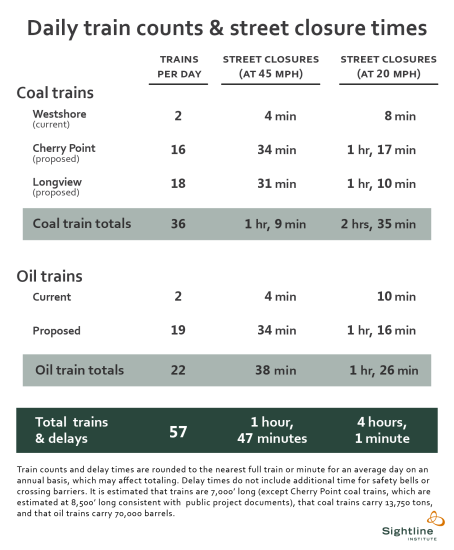

So massive are the fossil fuel industry’s plans that simple math shows that the shipments would close streets and roads for hours each day as trains pass through at-grade crossings.

In our depiction below, we select several representative communities where coal and oil trains will travel, but these are by no means the complete accounting of street closures in the area. In every place along the route, coal and oil trains would shut down streets and roads every single day from 1 hour and 47 minutes to 4 hours, on average, if all the plans were built and operated at full capacity.

After passing through Idaho, Spokane County, and eastern Washington, trains will make their way along the Columbia River, passing through small towns like Wishram.

Wishram, WA (Klickitat County)

The town of Wishram contains no public rail grade crossings, but it lies alongside the rail tracks that separate it from the Columbia River. Wishram Elementary and Wishram High School are visible in the grassy area to the north of the tracks. BNSF reports that about 30 trains pass through Wishram daily. Most are presumably freight trains, though the town does boast an Amtrak Station (designated with a blue square), and sees two passenger trains each day, one heading northeast to Spokane, and one bound west for Portland. Coal and oil trains could, in theory, nearly triple train traffic through Wishram and towns like it, potentially posing a problem for passenger rail reliability.

Traveling west, trains reach the little town of Bingen.

Bingen, WA (Klickitat County): Maple Street

Maple Street, shown in the center of this photo with a red square, is protected by crossing gates where 43 trains pass daily across the street. The crossing blocks access to the Port of Klickitat Industrial Park which houses a new aerospace manufacturer and SDS lumber, two of the major employers in the Gorge.

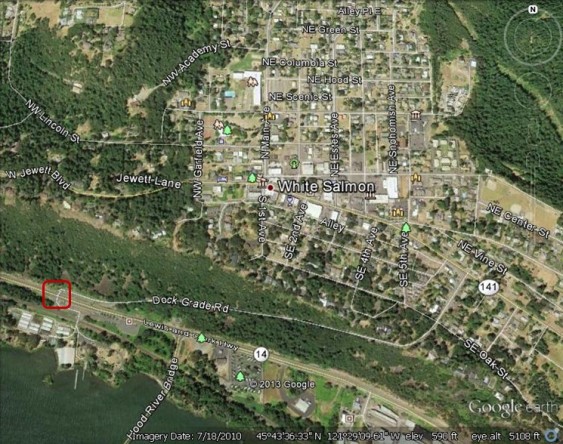

Further west in Klickitat County, trains reach White Salmon.

White Salmon, WA (Klickitat County): South Dock Grade Road

The town of White Salmon contains one public grade crossing at South Dock Grade Road. The crossing sees just 80 vehicles on an average day, but it is protected by gates. The community is further protected by a small hill that lies between the city and the rail line, and this may provide a modest buffer for noise, smoke, and air pollutants. Whitson Elementary School is the white L-shaped building to the North; the building for the White Salmon School District lies just to its southwest.

From White Salmon, trains continue west to reach Stevenson:

Stevenson, WA (Skamania County): Russell Avenue

One public BNSF grade crossing is found in the town of Stevenson at Russell Avenue. The crossing is protected by a gate from the 36 trains that currently pass through daily. Stevenson High School and its athletic fields are visible in the image to the north. The Russell Avenue crossing provides access to the Port of Skamania where numerous businesses are located, as well as the dock where visiting tourist boats land.

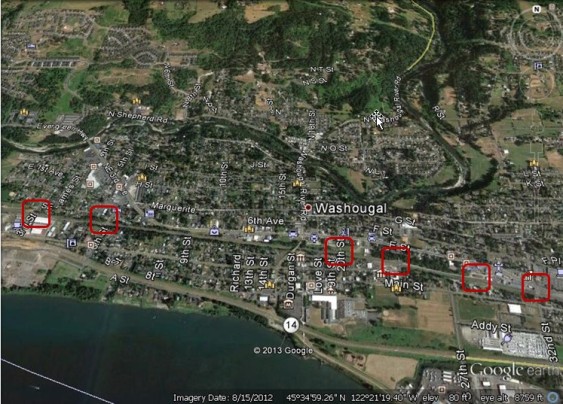

Further on, trains cross into populous Clark County, soon reaching the town of Washougal:

Washougal, WA (Clark County): 3rd, 6th, 20th, 24th, B, and 32nd Streets

Currently, about 35 trains per day close off streets in the heart of Washougal, which has six at-grade crossings. In the future, the number of trains could easily double if coal and oil shipment plans come to fruition. The consequences are potentially serious for both safety and traffic congestion. The B Street crossing, for example, is protected only by flashing lights, while the 32nd Street crossing, the busiest arterial of the bunch, handles 12,600 vehicles per day.

Coal and oil-bearing trains continue into ever more densely settled areas, next coming to Camas.

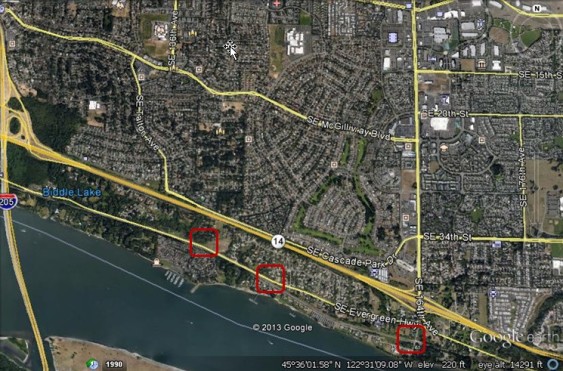

Camas, WA (Clark County): 139th, 147th, and 164th Streets

Three public streets cross BNSF tracks west of Camas. At 164th Street only flashing lights warn drivers of the heavy freight rail traffic on the mainline. With 1,250 vehicles on an average day, the busiest of these streets is 139th Street, which sits just north of the Steamboat Landing Marina. In the northwest part of the image, icons of children represent Crestline Elementary School and Wy’east Middle School.

Trains continue along the Columbia to reach Vancouver, Washington, a major regional city with a population of over 165,000.

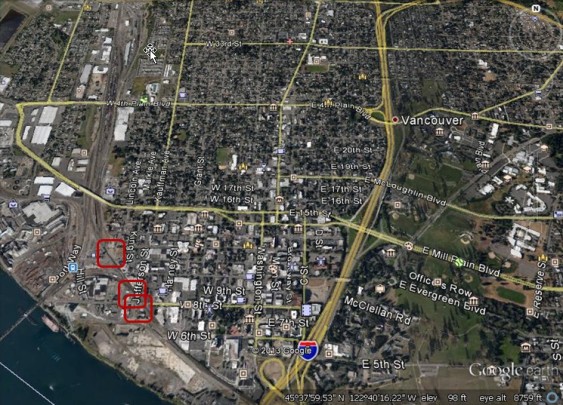

Vancouver, WA (Clark County): Jefferson Street, 8th Street, 11th Street

Home to a major railyard and infamous for its rail congestion, the city of Vancouver contains multiple BNSF grade crossings. The busiest crossings are at Jefferson and 8th Streets, where 88 trains daily shut off city streets. (These crossings are close together, and the red rectangles marking them overlap.) Just to their north, the crossing at 11th Street sees 32 trains daily. The crossing at 11th is marked only by a simple cross buck road sign; the crossing at Jefferson is protected by gates. The busiest crossing, with 5,300 daily vehicles, is 8th Street, but it is marked only by flashing lights.

It is here in Vancouver that the first batch of fossil fuel-bearing trains would reach their destination. The Port of Vancouver is weighing a gigantic oil-by-rail terminal proposal capable of handling 360,000 barrels of oil per day, which would require roughly five loaded and five unloaded trains daily.

The Vancouver rail system is undergoing a major taxpayer-funded overhaul. Even as the Port contemplates a big new influx of fossil fuel trains, the state transportation department is spending more than $150 million in public funds in the hopes of untangling Amtrak service from freight rail congestion, and to build a bridge at 39th Street (not shown) owing to the frequent street closures from trains.

From Vancouver, the BNSF mainline for coal and oil heads north toward Longview and other sites. We’ll take up that region in our next chapter.

You can enlarge the images by clicking on them.

Click here for notes, sources, and methodology.

John Abbotts is a former Sightline research consultant who occasionally submits material that Sightline staff turn into blog posts. Thanks to Devin Porter of Goodmeasures.biz for designing the table. Thanks to Peter Cornelison for information about local communities.

Have photos of a crossing featured in this series? Share them in our “Wrong Side of the Tracks” Flickr pool.

Comments are closed.