It must be a syndrome. A mass delusion of endless traffic growth. Or maybe the idée fixe that the future will resemble the 1950s.

Earlier in the week I mentioned that, despite years of declines on the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, Washington’s transportation revenue forecasts assume that traffic will soon start growing, quickly and inexorably. It might be funny if the fiscal stakes weren’t so dire.

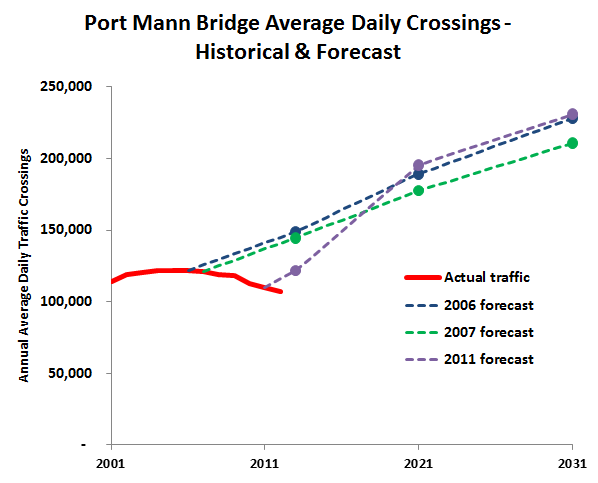

Apparently, the same mentality holds sway north of the 49th parallel. Consider the new Port Mann Bridge—a project of British Columbia’s provincial government that opened to traffic last fall. The province was anticipating a rapid increase in traffic to pay for construction. And while it’s too early to tell how the added road capacity will affect traffic volumes over the long haul, the declines in vehicle travel in recent years could make it very hard for the bridge to meet its toll revenue forecasts.

(Forecasts here; actuals here.)

As with the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, the traffic forecasts actually got wackier over time. Despite roughly a decade of flat or declining traffic, the province’s transportation planners in 2011 predicted that traffic would quickly catch up with where it “should” have been. In essence, the planners interpreted the slight decline in traffic between 2006 and 2011 as evidence that traffic would skyrocket even faster from 2013 through 2021.

I shouldn’t be too hard on the poor traffic forecasters. As Yogi Berra (or was it Niels Bohr?) allegedly said, “It’s hard to make predictions, especially about the future.” And that advice applies to me as well as to traffic planners—so I want to make it clear that I’m not actually predicting that real-world traffic won’t live up to the official forecasts.

Still, it’s increasingly clear that official traffic forecasts have become untethered from reality. At best, they’re based on outdated transportation models or “best practices” forged in the years when traffic volumes really were growing quickly. At their worst, they’re the result of coordinated deception to build public support for politically favored projects.

The fiscal consequences of failed transportation forecasts can be pretty dire: see, e.g., the $35 to $45 million annual hole that the Golden Ears Bridge is blowing through the lower mainland’s transportation budget, because toll revenues from the bridge aren’t keeping pace with projections, even as bond payments to pay for construction keep coming due.

But has the province actually learned anything from the Golden Ears shortfalls, or the flat-lining of gasoline consumption in the lower mainland, or the failure of its early Port Mann forecasts to line up with actual traffic? Apparently not. In fact, they’re doubling down on their risky bet on traffic growth, by moving forward with a costly and aggressive plan to replace the 4-lane George Massey Tunnel with a 10–lane bridge.

No doubt, the province will predict that rapid traffic growth will help pay for the construction costs for the new bridge, which could set the province’s taxpayers for quite a shock down the road: they could easily wind up paying for yet another highway project that was supposed to pay for itself.

Comments are closed.