Residents in West Seattle were anxious about plans to install dozens of roadside rain gardens used to control spills of raw sewage into Puget Sound. They were hearing horror stories about Ballard gardens that were slow to drain. Opponents organized and spread half-truths about green stormwater solutions, stories about massive sinkholes and mosquito infestations.

King County officials knew they had to earn the public’s support if the project was to succeed, and that it wouldn’t be easily done. They would need to bring out the big guns. They would need their little red wagons.

The county methodically built support over the course of years, and the stormwater lessons that they learned—from the use of wagons to more conventional strategies—can assist municipalities, nonprofit groups, and developers growing their own green infrastructure projects. Because while rain gardens and their eco-brethren are increasingly cropping up nationwide, the technology still can make residents anxious as their front yards are transformed into stormwater sponges.

Given these fears and challenges, King County officials proceeded in their effort with caution. Their objective was to reduce the sewage spills at the Barton Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) from an average of four per year, spewing a total of 4 million gallons of untreated waste, down to one spill annually.

So in 2008 and 2009, King County did an analysis to figure out which mix of pipes, holding tanks, and rain gardens could divert excess rainwater out of the sewers. They held community meetings and briefings to let residents know what was coming. By August 2010, county officials told folks that green stormwater infrastructure—and specifically the highly engineered rain gardens called “swales” that can soak up larger volumes of polluted runoff—was a strong contender as the most cost-effective solution for taming the overflows.

The county initially considered up to 64 blocks as possible locations for the swales. In 2011 and early 2012, engineers dug 29 groundwater monitoring wells and did a series of infiltration tests to track where the water went. In February 2012, King County officials held a public meeting to share their test results.

“People were curious, but not alarmed,” said Kristine Cramer, a county water quality planner who helped lead the public outreach.

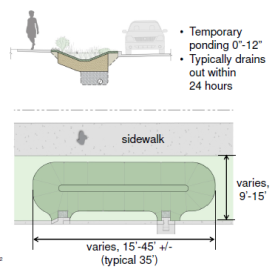

The county narrowed the Barton CSO project to 31 blocks, and in March officials presented preliminary design plans. Now people could better visualize where water absorbing landscapes would crop up along sidewalks, and street parking would be replaced in spots by swales.

“People were pretty excited at that time,” Cramer said. “Some were riled up. They wanted to have input.”

So that same month, the county divided the 31 blocks into four clusters and held meetings central to each location. They made giant maps and encouraged residents to post notes on them, identifying drainage trouble spots, highlighting beloved street trees, offering any comments they wanted to share.

But the anxiety and opposition grew. It was time for the little red wagons.

Building Support House By House

Over a single weekend in June, King County staff held 24 public meetings on streets where the swales would go. Using red wagons, they moved from spot to spot, presenting neighbors the March rain garden maps and contrasting them with updated maps, showing how they’d changed their plans to address public concerns. Staff rolled out life-sized tarps along the roads illustrating the dimensions of the swales and showing paths across the swales from the street to the sidewalk. Nearly 150 people participated.

Throughout the summer and into fall 2012, Cramer and others talked to people door-to-door. They answered phone calls and fulfilled residents’ requests to meet one-on-one. By October, officials narrowed the Barton CSO project to 19 blocks best suited to the swales. They held more meetings to connect with residents living in the more than 90 homes that would be getting the swales.

There was still some opposition, but often it came from residents on streets that were no longer even part of the project. People who were directly impacted pushed back against the naysayers and told them they were “in the way now,” Cramer recalled.

In early 2013, the county got permits for 19 blocks, decided they would build 15 blocks, monitor their performance, then finish the last four if needed. The first big phase of swale construction starts in February and March. But the public outreach will continue, including a 24-hour information hotline for residents to call.

Cramer points to two surprises in the Barton CSO project. First, she expected people to have a better understanding of what public spaces are—spaces such as the planting strip between roads and sidewalks—and how the government is allowed to use them. Even though residents don’t own that slice of lawn, many feel a lot of ownership toward that patch of green.

Second, while going door-to-door can sound like a costly, time consuming exercise, Cramer said it pays off and is a great way to get your word out and win support among skeptics.

People you reach, “they talk to their neighbors and that passes along, that King County is really responsive,” she said.

Seattle’s Stormwater Strategies

Around the same time that King County was embarking on its Barton project, the city of Seattle was building a series of roadside rain gardens in the Ballard neighborhood in order to curb sewage overflows to a different outfall. The Ballard project was fast tracked to take advantage of federal stimulus funding. The rushed, initial investigations missed drainage problems and neighbors publicly protested the gardens when they drained poorly.

Seattle Public Utilities, which led the project, corrected the problems and now the swales function as planned. Additionally, officials opted to swallow a heaping helping of humility and carefully deconstructed what went wrong. As a result, the city developed a detailed protocol for similar projects, identifying specific strategies for working internally with departments and elected officials, and for connecting externally with the public.

Seattle’s tips for successfully communicating internally:

- Contact all departments affected by the project, including roads, parks, utilities, etc.

- Hold brown bag lunches with people not directly involved and provide briefings for leadership to keep everyone in the loop.

- All departments working on a project need to have the same message to share with the public.

- Coordinate with other city goals including bike routes, street safety improvements, etc.

And let’s face it, green stormwater infrastructure is not your granddad’s solution for polluted runoff. Instead of digging a hole, burying some pipe, and walking away, these swales are front and center in a neighborhood.

“With green infrastructure, it requires going beyond the public meetings,” said Gretchen Muller, a senior associate with Cascadia Consulting, which has partnered with Seattle on stormwater work. You need to really engage residents “in a meaningful way.”

Seattle’s pointers for communicating with the public:

- Use one-way communication such as email messages, mailings, fliers at community locations like libraries and grocery stores, and signs at project sites.

- Use two-way communication including booths at community events and walking the streets talking to neighbors.

- Develop a clear timeline of the project and specific points at which the public can weigh in and help shape the project. Share photos of what the rain garden will look like right after it’s planted, and over the first couple of years.

- Offer a single, well-publicized contact person.

- Do on-the-ground research to figure out where street parking is most heavily used and locations of right-of-ways that are carefully planted and tended, where someone likely feels strong ownership.

- Talk to residents about problems that the project might solve for them, such as flooding and traffic calming.

- Make clear who in the city is responsible for swale maintenance and liability for injuries.

Portland has developed similar strategies for rolling out projects to control polluted stormwater runoff—see this earlier blog post with six tips for success. Like King County and Seattle, Portland officials encourage project leaders to reach out to the public early in the process and to take the time for in-person meetings.

Shanti Colwell, an environmental engineer with Seattle Public Utilities, reminds folks to look at the situation from the perspective of the neighbors and businesses.

“As the public views it, everything seems fine on their street,” she said. “And we want to talk about ripping things up.”

Seattle is in the beginning phase of constructing more rain gardens in Ballard, and is taking care to start the process with plenty of meetings and outreach.

Comments are closed.