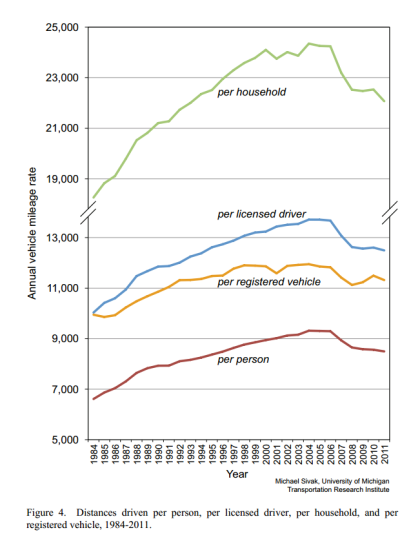

Interesting. Michael Sivak, a researcher at the University of Michigan’s Transportation Research Institute, asks: “Has Motorization in the US Peaked?” His conclusion: quite possibly so. A peak looks especially evident if you look at driving rates for the US light-duty vehicle fleet—which, by whatever measure you consider, all peaked in 2004, well before the onset of the 2008 recession:

According to Sivak, most previous looks at the issue of “peak VMT” have focused on total VMT, including long-haul trucks. Once you remove long-haul trucks, he says:

According to Sivak, most previous looks at the issue of “peak VMT” have focused on total VMT, including long-haul trucks. Once you remove long-haul trucks, he says:

[T]he combined evidence…indicates that—per person, per driver, and per household—we now have fewer light-duty vehicles and we drive each of them less than a decade ago…

These reductions likely reflect, in part, noneconomic changes in society that influence the need for vehicles (e.g., increased telecommuting, increased use of public transportation, increased urbanization of the population, and changes in the age composition of drivers). Because the onset of the reductions in the driving rates was not the result of short-term, economic changes, the 2004 maxima in the distance-driven rates have a reasonable chance of being long-term peaks as well.

An important caveat to all of this is that per capita reductions in driving don’t necessarily lead to overall reductions. As population grows, total driving could grow as well, even if per-capita rates continue their gradual decline.

That said, the vehicle travel data in recent years has clearly defied the confident predictions—some of them made quite recently—that driving rates would increase, inevitably and inexorably.

Comments are closed.