Editor’s note September 2016: As Seattle inexplicably backs away from a best-in-class opportunity to make parking work better for neighborhoods, Sightline brings back this audience favorite from our series about parking setbacks and solutions…

On the subject of curb parking, everyone seems to have a story—and what the stories reveal is surprisingly important to the future of our cities. I’ve been asking my friends, and I’ve heard an earful. Listen.

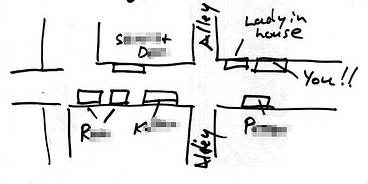

Soon after advertising executive Necia Dallas moved into a house in Portland, Oregon, she found on her door a detailed, hand-drawn map specifying the curb spots where each resident was permitted to park. The map, left by an anonymous neighbor, indicated that Necia was welcome to park in front of her own house but that it was, “Optional! Because of your driveway. <smiley>” Jon Stahl of Seattle also got a parking map as a housewarming gift (pictured above).

To claim the spots in front of their homes, people resort to illegal yellow or red curb paint, earnest oral pleas, or—above all—notes left on the windshield. Lots and lots of notes.

“Not here, man. Not here,” said one missive that Seattle architect Rik Adams got on his windshield.

A West Seattle resident’s read, “Dear Driver, This is not a park and ride. We the neighbors would appreciate if you would find another spot to park.”

Audrey Grossman’s said, “Don’t park your liberal foreign car on the American side of the street.”

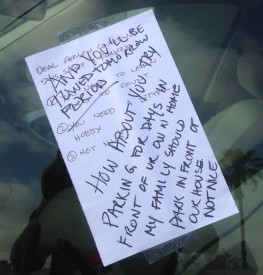

Brent Bigler of Los Angeles left a response to the note he found on his windshield in May and got an angry rejoinder. It says, among other things, “You’ll be towed tomorrow period” (pictured).

Some people even put up their own, extra-legal no-parking signs, like the one pictured from Shoreline (or the one described here). More creative is Steve Gutmann’s Portland neighbor who “has a fake plastic parking meter that he puts on his planting strip in front of his house.”

To enforce their claims, neighbors sometimes go to great lengths. Shaun Vine, when he trespassed on a curb space in Seattle’s Ballard neighborhood, found his car boxed in. A homeowner had punished him by parking two autos bumper to bumper with Shaun’s.

Worse is what happened to Jenny Mechem’s friend in Chicago who had the temerity to park in front of someone else’s house one winter day. Neighbors packed snow around his car and turned the hose on it, freezing it in place.

Renee Staton of Seattle says, “A neighbor unscrewed my windshield wipers (which flew off while driving on I-5 during a sudden downpour) and poured acid on my hood because I was parking in front of their house.”

Natalie McNair’s Tacoma neighbor got in his extended-cab Ford truck, put it in low gear, and plowed Natalie’s parents’ Subaru Outback out of the space in front of his house.

In San Francisco, Lisa Foster’s neighbor pushed her car into his driveway so that he could get it ticketed and towed. “I started using my emergency brake after that,” says Foster.

The good people of Washington, DC, have been known to egg curb intruders, and Angelenos sometimes throw paint at interloping wheels.

Mindy Cameron of Seattle remembers living in San Francisco and seeing an outsider park in front of a neighbor’s house. “The nice, otherwise calm, young professional neighbor,” she said, “came downstairs in his khakis and button-down shirt, and smashed in the guy’s front window with a baseball bat.”

A brief history of parking

Curb parking, it seems, is the stuff of neighborhood psy-ops. It brings out the crazy in people. And that fact—our intense, animalistic territoriality about curb parking—is among the fundamental realities of urban politics. It’s a root cause, I argue, of most of what’s wrong with how cities manage parking. And much is wrong with how cities manage parking.

Consequently, somehow defusing or counteracting this territoriality could release a cascade of good news, if it allows cities to manage parking better. Parking policy is a secret key to solving urban problems ranging from housing affordability to traffic, from economic vitality to carbon pollution—plus a snarl of other ills. Parking reform is that important, as later articles in this series will document.

In this article, however, my goal is to explain how we got our current parking rules and why we may finally have a chance to undo them.

Most of a century ago, the tradition of free curb parking—a vestige of the age of horses and hitching posts—collided with exploding numbers of Model Ts and collapsed into clogged street sides, double parking, and epidemics of cruising for spaces. For city leaders, the competition among motorists for curb spaces became an unrelenting headache.

Strategies for managing it were primitive. The crude and unevenly enforced first-come, first-served rationing system still in effect began to evolve: “No Parking” signs, 1-hour and 2-hour parking limits, loading zones, plus enforcement by parking agents. Later came parking meters: Seattle installed its first ones in 1942. Later still came resident-only parking districts in neighborhoods adjacent to busy destinations such as hospitals and universities.

Mostly, though, cities tried to solve the problem of crowded curb parking—and neighbors’ political pressure to keep newcomers out of the “their” spots—by building wider streets and boosting the supply of off-street parking. In the 1940s and 1950s, they began writing into their land-use regulations detailed requirements that each new building provide ample off-street parking—enough to accommodate every driver likely to visit that building without anyone spilling over onto the street.

Seattle, for example, imposed parking minimums in 1958. For each type of building, whether an office, restaurant, grocery store, apartment building, auto parts store, or whatever else, city law imposed a prescription: two spaces per apartment, for example, or five per thousand square feet of retail floor space. The rules varied widely from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, and they had, as I will explain in another article, no empirical basis whatsoever. In the words of UCLA professor and parking guru Donald Shoup, whose research on parking inspired this series, they were “nonsense on stilts.”

For all their analytical bankruptcy, however, their consequences were gargantuan. “Form,” architects sometimes quip morosely, “follows parking.” Parking rules dictated what designers could inscribe on their blueprints. Those diagrams then printed out across the urban and suburban landscape as what we now think of as classic sprawl: islands of building surrounded by seas of parking, big garages in front of big houses, courtyard apartments encircling asphalt, and other hideous built forms that Sightline fellow Alyse Nelson has detailed.

[list_signup_button button_text=”Like what you|apos;re reading? Get our monthly housing |amp; urbanism updates straight to your inbox!” selected_lists='{“Housing Shortage Solutions”:”Housing Shortage Solutions”}’ align=”center”]

Most of these rules remain in place, an invisible but massive bulwark of off-street parking minimums, unreformed and rarely discussed. As a cure for curb-parking scarcity, they are worse than the disease. They’re like prescribing cigarettes as weight loss therapy: you’ll likely lose weight, all right, but you may ruin your health or even lose your life.

To change these rules, though, it’s critical to understand the political dynamic that created and perpetuates them.

The politics of parking

Curb-parking territoriality—the stuff of the stories I opened with, the indignant reaction many of us have when we see a car in front of our home and ask “Who parked in my spot?!”—is the key to understanding the dynamic. Like any pack-forming, territorial mammal, we want to expel interlopers. That primal, instinctual reaction is at the root of off-street parking requirements. Urban planners and lawyers may think of on-street parking as public property: a shared, public resource to be managed for the common good. Most home owners—and most voters—think of curb spaces as their own, their domain, their property.

Developers of new buildings, for their part, do not want to be told how much parking to install; it boosts their costs, limits their options, and trims their profits. On the other hand, as long as parking rules are citywide, developers can often pass much of the cost along to the future owners or tenants of their buildings.

[button link='{“url”:”http://www.sightline.org/2013/08/22/apartment-blockers/”,”title”:”Related: Outdated parking rules raise your rent.”}’ color=”green”]

Meanwhile, local officials, few of whom seek public office in order to adjudicate disputes over parking, are typically quick to take the path of least resistance. Confronted with territorial voters, they bury the “solution” to parking disputes in the arcana of the land-use code. They impose or maintain sweeping requirements for off-street parking. By doing so, they protect current residents of neighborhoods, and they send the bill for new parking into the future.

Future residents will pay more for housing, and future businesses will pay more for commercial real estate. As result, there will be less of each. But these groups have no say over parking policy today.

Professor Shoup likens this political dynamic to “taxing foreigners living abroad”: an unfair policy that virtually all politicians would adopt, if they could. Other ill effects of off-street parking mandates, such as upward pressure on grocery prices and the rest of a city’s cost of living, are so hidden and dispersed, that virtually no one recognizes them as a consequence of parking requirements.

From these conditions—curb parkers as territorial as baboon troops, developers able to pass along costs, and politicians capable of billing future newcomers—off-street parking requirements have emerged almost everywhere. They’ve done their job, massively inflating parking supply. In most parts of most towns, parking requirements boost the number of spaces enough that parking supply floods the market, and the price drops to zero. People park for free, and competition for curb spaces is minimal.

Specialists have been apoplectic about the perversity of off-street parking mandates almost since the rules spread across North America in the post-World War II years: the hidden costs to human health and safety, local economies, air quality, and housing affordability are stark. But change has not come. Reasoned arguments have not mattered.

Why? Because the prevailing arrangement works in the one arena that actually matters to local elected officials: politics. Ample off-street parking quotas balance the political interests that count—current residents (especially property owners), incumbent businesses, and developers. Consequently, they’ve remained frozen in law for a long time.

Change for parking

Now, though, conditions are gradually shifting, and the resulting thaw is beginning to favor reform. Demographics and driving patterns are different. Information technology is breaking up the ice floe of prevailing parking economies. And a new policy model for parking has emerged. It’s a new, three-step game plan from Professor Shoup that neatly reverses the vicious political circle perpetuating off-street parking mandates.

The steps are to:

- Charge the right prices for curb parking spaces,

- Return the resulting revenue to the neighborhoods from which it was collected, and then,

- Repeal off-street parking requirements.

The first step solves the original urban parking problem: overcrowded curb spaces. The second engages a political force (greed) that’s strong enough to neutralize parking territoriality. The first two steps, furthermore, eliminate the primary motive for off-street parking mandates. They set in motion a new, virtuous circle, in which communities no longer resist but instead seek to maximize on-street paid parking, because it funds projects that boost their property values and profits. This approach can convert communities from a defensive posture toward “their” spaces to a welcoming posture toward potential on-street parkers. It turns those parkers from interlopers to benefactors.

That’s a much-abridged version of the argument of this series. Next time, I’ll begin giving it a full exposition. In the meantime, you might amuse yourself by asking people you meet if they’ve ever had neighbors go crazy about people parking in “their” spots. Everyone seems to have a story.

You’ll find more on residential parking and housing in our new e-book, Unlocking Home: Three Keys to Affordable Communities.

Comments are closed.