We’ve written before about the “high occupancy/toll” lane experiment on Washington’s SR-167. But for those unfamiliar with the concept: HOT lanes are special highway lanes that transit and carpools can travel in for free, but are also available to solo drivers who are willing to pay a toll. When the regular lanes start to back up, the HOT lane tolls increase. That way, the HOT lanes never get clogged, even when the regular lanes are full.

Besides keeping carpools and transit moving, the SR-167 HOT lanes have an additional value: they give researchers more nuanced understanding of how much people are willing to pay for a quick trip. And when we took a look at the SR-167 HOT lane data last year, the numbers surprised us: apparently, drivers really aren’t willing to pay much for a faster commute. Few drivers on SR-167 opted to the free-flowing HOT lanes, so HOT lane traffic volumes typically stayed low.

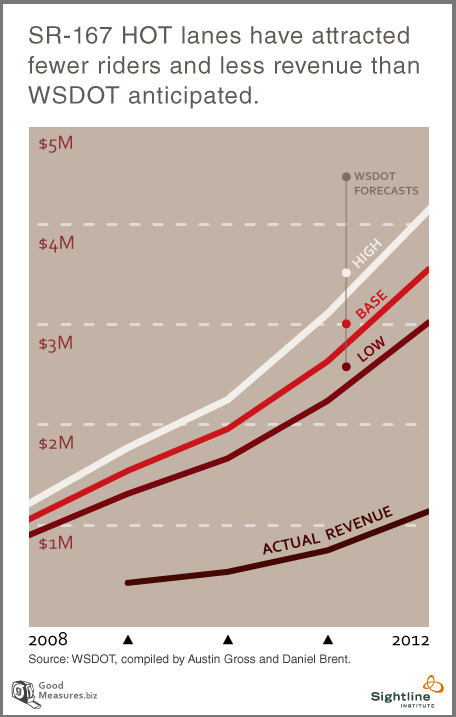

University of Washington PhD students Austin Gross and Danny Brent have taken our initial research several steps further. I’ll probably mention more about their work in a subsequent post. But in the short term, I was struck by their data showing how badly WSDOT transportation planners misjudged demand for the HOT lanes:

That’s right: actual HOT lane revenue in 2012 was about one-third of the “low case” projection that WSDOT made before the lanes were opened. That was likely due to two separate effects: fewer cars than anticipated using the HOT lanes; and lower toll rates needed to keep HOT lanes from clogging up. Both effects flow from flawed early assumptions and beliefs about how much demand there would be for driving in general, and for the HOT lanes in particular.

These findings don’t prove that HOT lanes are a bad idea! But they clearly have a bearing on today’s transportation debates. For well over a decade, the Washington and Oregon departments of transportation been planning massive highway megaprojects—wider urban highways, higher-capacity bridges, expensive tunnels, and more. And they’ve pursued these plans in the belief that bigger highways will ease congestion—and that drivers put a high value on congestion-free trips.

But the SR-167 HOT lane experiment shows that most drivers on that stretch of road simply aren’t willing to pay much for a fast commute. Which raises a question: given that drivers may not be all that willing to pay for a quicker trip, does it really make sense for taxpayers to invest so much in trying to give them what they won’t pay for themselves?

Note: just to be clear, the interpretations of Gross’s and Brent’s numbers are my own, not theirs. And their research goes much, much deeper into the specifics of pricing and driver willingness to pay; the chart above is just the tip of the iceberg. I’m very much looking forward to diving into their findings! And hat tip to GoodMeasures.Biz for the graphic!

Comments are closed.