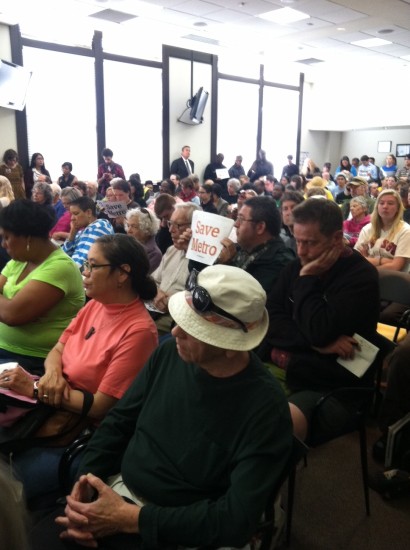

Here’s a picture of hundreds of people who crowded into a hearing room Tuesday to protest looming and massive bus cuts at King County Metro. If this looks familiar, it’s because we went through a similar exercise two years ago. This time, if the Washington State Legislature doesn’t grant the transit agency new taxing authority to backfill an immediate $75 million budget hole, Metro says it will begin eliminating 600,000 service hours next fall, or 17 percent of the transit service it currently offers.

So what does that look like? Well, for starters, they would be the largest service cuts in Metro history. About 70 percent of current riders would be negatively affected: Some people will lose bus service entirely, some people will have to walk further to get to a stop, a lot of people’s buses will run less frequently, and a lot of buses will be more crowded.

It would, in short, be a fairly epic change in the wrong direction for a growing county that prides itself on being green and economically savvy yet hasn’t sufficiently agitated for a stable funding source for the very service that efficiently delivers people to their jobs and allows them to do errands without clogging up roads and spewing carbon pollution. Seriously, just spend a minute with this interactive map that shows just how the cuts might go down.

In Seattle, parts of Leschi and Montlake could lose all bus service, as would all of Maury Island and some neighborhoods in Issaquah, Mercer Island, Shoreline, North Bend, Kent, the Sammamish Plateau and dozens of other communities. People who live in Sunset Hill, North Beach, or Vashon Island could find themselves bus-less outside of the morning and evening commutes. On busy routes, more riders (who will likely have just seen their fifth fare increase since 2008) will be stranded at stops while packed buses pass them by.

Forget, for a minute, all the people who rely on Metro to get to their jobs: The architects and biotech scientists and project managers who have access to cars and won’t be shy about using them if buses become too inconvenient, or the people who take Metro from Tukwila or Carnation to get to jobs cleaning hotels and guarding courthouses and staffing parking booths in downtown Seattle. And forget about anyone who, by choice or necessity, gets around the city without a car.

Here’s why everyone else in the region should care: A more anemic Metro system will, without a doubt, make everyone’s life harder. Think about what happens when the Alaskan Way Viaduct comes down, or when bridges to the Eastside need replacing. Construction, or tolls, dump more cars on local streets, gumming up bus routes and making service slower. Getting around by bus starts to become more unpleasant because Metro has just whacked nearly 20 percent of its service and overloaded routes that survived. And the agency has zero money for new investments that could help an ever-growing population to get to jobs and baseball games and Microsoft meetings without considerable hassle.

So what do people do then? They avoid downtown and other congested areas entirely, which is why business organizations like the Downtown Seattle Association and Seattle Chamber of Commerce are lobbying for new transit money. Some will get back in their cars; Metro estimates the service cuts will add 25,000 to 35,000 vehicles to the region’s roads each day. That screws everyone else who’s trying to get around and a regional economy in which businesses depend on things being delivered in a timely fashion.

Oh, and those who don’t have the luxury of hopping back in their cars will just be, well, screwed. Because they’ll be shelling out more money in fares for longer waits and sketchier service. And businesses—from hospitals to law firms to the airport—will have more trouble maintaining a stable workforce.

How did we get into this mess?

In short: More than a decade ago, voters reduced the Motor Vehicle Excise Tax levied on cars and replaced that relatively stable funding source for King County Metro with a portion of sales tax, which now makes up about 60 percent of its operating funds.

But sales tax revenue is volatile, and as the national recession unfolded and people stopped spending so much money, sales tax revenues dropped by nearly 18 percent. That left the transit agency with a $1.2 billion budget shortfall from 2008 to 2015. Until now, the agency has weathered its fiscal cliff without major cuts in overall service (though it did eliminate the downtown free ride zone and made real cuts to many routes last year, that service was actually reallocated to busier routes.)

It has also raised fares four times, spent its reserves, delayed expected service expansions, and negotiated a bigger share of county property taxes. Faced with a similar level of massive service cuts in 2011, the legislature granted the King County Council the authority to approve a temporary congestion reduction charge that raised vehicle fees by $20 for Metro. But that was only for two years until a more permanent solution could be found. That stopgap funding will expire in the middle of next year, and the reserves that Metro has been borrowing from will be exhausted at the end of 2014.

What can we do about it?

King County Metro needs a stable and sustainable funding source, so it doesn’t have to beg for band-aid funding every other year, traumatize its most vulnerable riders with visions of transit Armageddon, and constantly rearrange deck chairs with no new money as it’s asked to cope with major traffic and congestion issues in the region that were not of its making.

In fact, a transit agency that serves the state’s most populous and economically important county actually needs to grow, just to keep up with people moving here.

Here’s what Metro most wants: The state legislature to give King County the authority to levy a new (up to) 1.5% Motor Vehicle Excise Tax (MVET), which would be split 40% for roads and 60% for transit. An owner of a car worth $10,000 would pay $150 a year, and the tax would generate about $85 million for Metro and $55 million for road maintenance.

Right now that MVET option for King County is frustratingly embedded in HB1954, a larger transportation revenue package that puts highway mega-projects ahead of virtually everything else (we and others have enumerated its terribleness here and here). It’s still alive in the special session that just started in Olympia this week, but it’s fate is very much up in the air.

King County could always try again next year, but it would already be deep in the process of eliminating and reducing service. And it would be difficult, if not impossible, to get a new MVET program up and running in time to stave off the first wave of bus cuts. So, how about we save everyone a lot of heartburn and just give King County the opportunity to fix it now? It shouldn’t be so tough for the state legislature to empower the people who live here to decide what kind of transit system they’re willing to pay for.

Here’s what some of those King County residents had to say at Tuesday’s hearing:

This is not a recipe for continued economic recovery. We just got out of the recession. We can’t let this bus service go now. —Kate Joncas, President of the Downtown Seattle Association

We simply cannot allow these cuts to occur, nor can we afford the human and economic costs if the legislature kicks the can down the road to the next session. —Josh Kavanagh, Director of Transportation for the University of Washington

I take the bus everywhere even though I own a car. It’s such an egalitarian thing, just like the library, which I also love. Whether you’re rich or poor or middle class, everyone can ride the bus if they don’t raise the fares too much. But the cuts coming are really immense, especially when you take into consideration that there’s not enough bus service as it is. —Sue Hodes, ESL instructor at Bellevue College

There’s a lot of us who have disabilities that make it difficult to drive and there’s many of us who cannot afford to drive. For us, it’s a matter of losing our jobs. —Siri Schroder, transit dependent South Lake Union resident and banquet server at a Bellevue hotel

I’ve been a bus rider by choice for a lot of years, but now by necessity I am. I use transit to connect me to my grandchildren, to groceries, to meetings like this, to museums and parks, to the symphony. Transit is the difference in my ability to remain a productive citizen in this city —Lois Laughlin, who relies on the following routes that would likely be affected by service cuts: 2, 5, 8, 11, 10, 12, 43, 72, and 16

Bellinghammer

Good article, thanks! If it comes down to HB 1954 or nothing, I hope Sightline will have the courage to oppose it. We need local options, but not this way.

Benn

How about this for a stable funding source….People put money in the fare box based on what it costs to deliver services! Metro needs to decided if it is going to be a transportation agency or social welfare agency, or try to be both, which is doing now (poorly). If it is going to try to be both, it needs to clearly separate operations to serve the very two different constituencies that are 1) commuters and hose who rely on Metro as their primary method of public transportation. I am not saying that some suability is not deserved based on the benefit of reduced use of the road system, but the subsidy should be way less than it is today. I have no problem paying taxes to help support a limited and highly subsidized system for people in need who use the bus as their main transportation to get around during the day. I do have a huge problem continue being taxed to subsidizing a system for commuters to go to work downtown who could affort to pay more.

Metro needs to consider more options at the fare box like variable pricing whereas mid day inter neighborhood routes are the ones that are subsidized while morning commuters on packed express busses pay fares that cover the entire cost of operating their routes. And by entire costs, I mean all of them…operations, maintenance, overhead, and capital improvement set asides for future development. At the very least peak time commuter fares should be more aligned with the cost of driving and parking downtown. The costs would adjust based on demand at different times of the day. This kind of fare structure would also help adjust demand. And I am sure there will be issues with this just as there were with 520 tolls and things will be bumpy for a while, but over the long term market forces will prevail and thing will stablize as we adjust to the new realities.

JohnS

Benn, the low-income fare task force has been talking about options to provide a better subsidized option for those who need it most.

But I think you’re missing the point. Cities everywhere heavily subsidize transit (or their regional governments do, or whatever) and for good reason. The volume of people who are transported by transit is huge compared to the equivalent cost in road capacity for single occupancy drivers. Could some commuters pay more? Sure. But that same transit service that carries commuters to and from their jobs carries people to the park, school, symphony, place of worship, library, and more. There’s no easy way to differentiate between these things. And from what you’ve written, you appear to see transit as strictly a job/commute connection, which is shortsighted compared to what transit already is in many of our urban neighborhoods.

The only way I could get behind something like this is if you said, OK, peak-only suburban express routes will have an additional surcharge (because that type of service is the most expensive to operate).

George

So, if the legislature gave the County the local MVET taxing authority they are asking for, Eymann could then run a statewide referendum to give ALL voters of the state (not just King County Voters) the right to repeal that authority. If it passed statewide, we would be back where we are.

Why would that happen? Eymann has a long history of opposing car tabs (via the MVET) being more than $30. At a statewide, macro-level, voters are sending socially liberal and anti-tax legislators to Olympia. It is a libertarian/populist idea with deep roots in the Washington Electorate. Those voters tend to see authority for a new tax anywhere as a threat to low taxes everywhere. So a repeal by statewide voters is a distinct possibility.

So I don’t have a problem with all of us making the case to Olympia for the right to tax ourselves to continue to fund Metro and other King County Transit. It beats the alternative; however, we need to prepare, as Metro apparently is, to live without the revenue for the reasons stated above.

The statewide electorate repealed a soda and candy tax imposed under Gregoire, and approved by that legislature, to provide small mitigation to social service cuts. Unfortunately, that is where the statewide electorate is still at. We in Seattle and King County need to recognize that reality, and that a majority of votes, for more taxing authority at the local level, or more taxes at the state level, will likely not be upheld in a referendum submitted to the people. There are any number of interest groups prepared to file and fund such referenda, not just Eymann.

John Niles

One issue associated with King County Metro needing more revenue is its long-term, year-after-year rise in operating cost per hour of transit service, a rise that for over a decade has exceeded growth in the cost of living.

Rising fixed-route transit cost per hour is also predicted in the Puget Sound Regional Transit Operators Committee to continue on into the future. See the graphs at http://www.bettertransport.info/pitf/SeattleTransitCostIssue.htm

Will this cost growth issue — a threat to the financial sustainability of public transit — ever be explained to the public? Where are economies of scale? Where is innovation in service delivery? Where is productivity improvement?

One hint — this rise is not completely explained by the cost of diesel fuel as peak oil has approached.

Metro’s response on this issue in its recent strategic plan update: “In 2012, our preliminary cost per hour increased by 4.9% as a result of increases in bus maintenance costs, insurance, security, and other central services. This is more than the 2.1% increase in the Consumer Price Index. Our cost figures for 2011 reflected an unprecedented wage freeze for King County Metro employees. Cost-containment efforts continue, as evidenced by the fact that Metro’s actual expenditures for 2012 were less than projected in the budget.”

This carefully-calculated alibi-speak is not good enough for me.