Clark

Even after years of staring at it, I never realized until this week that the oh-so-familiar recycling symbol is in the shape of a Möbius strip.

Wow: Google’s Earth Engine now displays 28 years of satellite images, pretty much anywhere on the planet. Here’s an aerial time-lapse view of coal mining in Wyoming. Here’s the growth of Las Vegas. I won’t depress you with views of Amazon deforestation, but I’d encourage you to use the search tool to take a look at greater Seattle: the areas that were urbanized in 1984 didn’t change all that much, but you can clearly see the sprawl and clearcutting on the urban fringe. To me, aerial images like these help put debates about the health of Puget Sound in context: over the long haul, the biggest threats to the Sound come from the ways we’re changing the landscape of the watersheds that feed the sound—which is all the more reason to work to curb low-density sprawl, and the transportation infrastructure that makes it possible.

Anna

It’s something Washingtonians don’t like to think about, but a problem we stew about a lot nonetheless: “The most toxic and voluminous nuclear waste in the US—208 million liters—sits in decaying underground tanks at the Hanford Site (a nuclear reservation) in southeastern Washington State.” It may be worse than we thought. This Scientific American article warns that Hanford clean-up may simply prove too dangerous to carry out.

I know every little kid is tempted on hot days spent in the back yard. I know it’s way more fun than water delivered any other way. But, don’t let your kids drink out of the garden hose. Here’s the terrifying skinny on the high levels of hazardous chemicals, many of which have been banned in children’s products, that are found regularly in garden hoses. (The only good news: There’s a bit less lead in garden variety hoses than there was a couple years ago. But, um, there’s still lead in them too!)

Here’s another photo essay worth checking out: What a week of groceries looks like around the world. (I found it particularly noteworthy which countries consume most of their food packaged in plastic and which ones seem to eat food that’s never even come into contact with a plastic bag—and which looks more appetizing.)

Finally, here’s some pretty awesome video of straight people being asked the type of question gay people are asked all the time about their sexuality: When did you choose to be straight?

Eric

Watching the Seattle City Council engage in the eight millionth battle in our local density wars—this time, the South Lake Union rezone—strengthened my conviction that the city needs a sort of Affordable Housing Master Plan, similar in scale and ambition to the excellent Climate Action Plan and Transit (and Bike and Pedestrian) Master Plan we already have. The city’s affordable housing goals ought to be less nebulous and ad hoc than they are (or at least than they appear to me), and they ought to be informed more clearly by a rigorous analysis marking out a path to achieve them.

Toward that end, I enjoyed reading Sharon Lee’s criticisms of the rezone legislation at Real Change and The Slog. Lee is executive director of the Low Income Housing Institute and she brings a valuable data-driven pragmatism to the debate.

Washington State Representative Reuven Carlyle released his annual survey of state tax spending and flow. If there’s a better analytical project in service of sane tax politics in this state, I don’t know what it is. The data reveal that most of the state’s more liberal counties are tax “donors,” getting back less in expenditures than they generate for the state in revenues, while many conservative counties, especially east of the Cascades, receive far more in spending then they generate. King and San Juan Counties are particularly notable, each receiving back only about 65 cents for each tax dollar they provide.

In Unburnable Carbon 2013, Carbon Tracker and the Grantham Research Institute make the case that we are in danger of winding up with costly wasted capital and stranded assets, particularly in the fossil sector, unless we soon begin allocating our investments according to the carbon constraints that we will one day have to realize.

The Seattle Transit Blog brought welcome news that the Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest is studying alternative transportation. Clearly it’s not possible to serve every possible destination in the sprawling national forest, but there are certainly marquee destinations that would be easy to serve. A year-round Seattle/Bellevue to Alpental run, for example, would be easy to imagine, providing access to prime country.

Serena

Dominic Holden has a brilliant piece in The Stranger this week on the controversy over micro-housing options in Seattle—though, frankly, it’s a piece urban planners anywhere struggling with questions of density and development should read. Holden thoughtfully engages the various arguments put forth by opponents of these much needed, less expensive housing options, and he demonstrates the prejudice underlying their opponents’ efforts. “Accommodating our growing population by shipping workers into the low-density sprawl of the exurbs is not the way a city should operate—and it reeks of inequity and classism.” (Additionally, if you’ve ever used Swifty Printers, you won’t do so again.)

And now for something completely different, “slacktivism.” Thoughts? And the original commercial:

Alan

Enrique Peñalosa points out that the next few decades of city building around the world will probably be the biggest ever: a global population surge is tapering off at the same time as urbanization is at full speed. City building in the United States will have especially large implications, both because of the country’s high rates of resource consumption but also because other nations’ cities may continue copying American urban form.

He then makes the case for “a dense city with a large percentage of buildings facing pedestrian-and-bicycle-only promenades or greenways…. Imagine a Manhattan crisscrossed by greenways.” He also calls for most urban waterfronts to become public promenades, not roadways or private land.

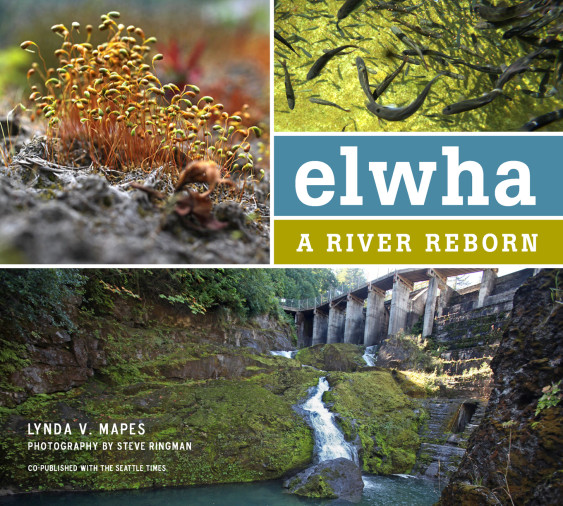

The Olympic Peninsula’s Elwha River is, in some ways, the perfect allegory for Cascadia and its future. The river runs a steep, rain-forest-lined course from the heart of the Olympic Mountains northward to the Strait of Juan de Fuca. It once boasted some of the biggest, fiercest salmon in all the world. Then, a century ago, our human predecessors stapled closed this artery of the peninsula, damming the river a scant few dozen miles from tidewater. Two giant concrete walls blocked passage of the river’s salmon into most of the Elwha’s valley, from foothills to headwaters. This habitat, now protected in the Olympic National Park, is more wild, pristine, and salmon-ready than any dam-blocked place in Cascadia.

The Elwha is an opportunity for ecological restoration and the rebirth of a sustainable economy—salmon!—on a monumental scale. Seizing this opportunity has been the work of decades for an array of tribal leaders, conservationists, fishing interests, and their political representatives. It has taken far longer than it should have, yet the critical stage of the task is nearing completion. One dam is now gone; the second is almost gone, too. (Sightline’s most-watched video ever shows a time-lapse view of dam removal, and you can see all that’s left of the second dam on this Park Service webcam.)

Compared with most of the industrial world, all of Cascadia is like the Elwha watershed. We have a larger share of our original ecological endowment intact. Our whole region is a monumental opportunity for ecological restoration and sustainable economy. Our progress in seizing this opportunity has taken far longer than it should have, but we are also father along the path than are other parts of North America.

Because of the Elwha’s allegorical place in my mind—and the memory of a visit to the lower river with my ex-wife in 1990 when love was young and new and the green of the vegetation along the banks was nearly magical in its beauty—I’ve long been fascinated by the place.

So I’ve been anxiously awaiting the release of Lynda Mapes’ definitive book on the Elwha’s restoration. One of the Northwest’s leading journalists, Mapes has been covering the resurrection of the Elwha for years. She’s put in weeks in interviews, tramping the river banks with scientists and digging through archival materials. Her book is a tribute to this undertaking commensurate to the importance of what’s unfolding there. Steve Ringman’s photography completes the package, and the Mountaineers Books and the Seattle Times together published the resulting Elwha: A River Reborn. It may be 2013’s most important environmental title in Cascadia.

As Mapes makes clear, even after the second dam’s removal is completed this year, the river’s restoration will take decades. But once the second dam is gone, the forces of nature will carry the restoration forward ineluctably. Let’s hope that a similar dynamic holds true for Cascadian sustainability more generally: that once we’ve accomplished some of the key tasks, such as putting a price on carbon, progress will gain momentum and carry itself forward ineluctably.

You can hear Mapes discuss the book at one her upcoming readings.