Last time, we reviewed accessory dwelling units’ (ADUs’) paucity and slow pace of development in most of the Northwest outside of Vancouver, BC. This time: the constraints that bind them.

Why are accessory apartments and cottages so rare? One reason, no doubt, is that many homeowners do not want to host an ADU. But a more pernicious reason is that winning approval to rent out an ADU in most cities requires running a harrowing gauntlet of rules. For every decision that Vancouver, BC, has made to welcome secondary suites and laneway houses, other cities have made the opposite decision.

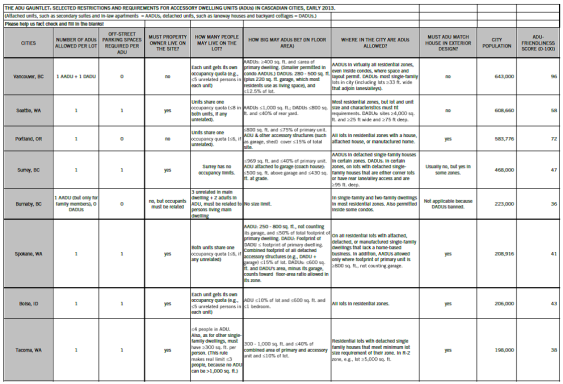

To map the restrictions on ADUs, Sightline assembled a table of ADU rules called The ADU Gauntlet that you can download and review here (or by clicking below).

Aided by collaborators at the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality’s Green Building Team (DEQ), we evaluated how welcoming cities across Cascadia are to ADUs. The cities we studied include the 30 most populous municipalities in the region, from Vancouver, BC, with more than 600,000 residents, to Idaho Falls, with almost 60,000. DEQ also gathered information from 16 smaller cities in Oregon, ranging from Corvallis, with more than 50,000 residents, to Damascus, with only 10,000. Together, these 46 cities hold 5.9 million northwesterners, a large share of the region’s metropolitan dwellers.

For each city, we attempted to answer questions about seven major legal barriers to ADUs: How many ADUs are allowed per lot? How many additional off-street parking spaces does the city require for each ADU? Does the city mandate that the owner of an ADU live on the lot where it is located, either in the house or the ADU? How many people may live in an ADU, in its accompanying house, or in both combined (that is, how do the “roommate caps” or occupancy limits about which we’ve spilled a lot of ink affect ADUs)? How big may ADUs be? In how much of the city may owners install ADUs? And must ADUs match the exterior design of the house they accompany?

Seven questions and 46 cities yield a table of 322 cells, each of which we attempted to fill through close reading of city land-use codes and consultation with city staff. DEQ and Sightline cooperated on this research. One result of many hands participating is that a few errors may have found their way into the table, especially concerning smaller cities. Please let us know of any that you see, so we can update the table. At publication time, 24 cells remained filled only with question marks. Almost all of these unanswered questions concern the smaller Oregon cities at the bottom of the table, and many of them are about how occupancy limits apply to ADUs. Some city codes are silent on this question.

Distilling elaborate rules from 46 cities into a single table leaves out many details. Many of them are evident in the more-thorough version of this table maintained by DEQ on its website. There, you can read the relevant portions of, and find links to, many city codes. The appended ADU Gauntlet table does, however, convey what a would-be developer or homeowner must do to win a permit for an ADU.

Case in Point: Tacoma

No city is typical, because rules vary widely, but the city of Tacoma sits in the middle of the pack in many respects and therefore exemplifies as well as any city the gauntlet Cascadia makes ADU proposals pass through. It illustrates the gauntlet and also shows how to read the ADU Gauntlet table. In Tacoma, ADUs are legal — either one AADU or one DADU per residential building lot. Tacoma mandates one separate off-street parking space per ADU. Typically, a parking space plus the driveway to get to it gobble about 300 square feet of surface area. The owner of the primary house must live on-site, either in the house or the ADU, and no more than four people may live in the ADU. Also, the ADU must have at least 300 square feet of floor area per resident, which means that the minimum size of an ADU is 300 square feet. This rule bans many of the tiny, tricked-out houses that Sightline has written about elsewhere.

Meanwhile, Tacoma caps ADU size at 1,000 square feet. (Notice that this maximum size actually reduces the legal number of residents from the officially stated four to three, because of the 300-square-feet-per-person rule. To house four people, you’d need 1,200 square feet.) Furthermore, the 1,000-square-foot maximum notwithstanding, a Tacoma ADU may never be larger than 40 percent of the size of the ADU and house combined. So, for example, a 1,200 square foot house may have an ADU no larger than 800 square feet (1,200 + 800 = 2,000, of which 800 is 40 percent). At 800 square feet, an ADU may no longer house more than two people, because of the city’s 300-square-feet-per-person rule. What’s more, an ADU may not exceed 10 percent of the size of the lot it is on: on a standard 5,000 square-foot lot (common in many Northwest cities), Tacoma therefore caps ADUs at 500 square feet. At 500 square feet, occupancy may not exceed one person, because of the 300-square-feet-per-person rule.

Tacoma’s code allows ADUs on residential lots that exceed minimum sizes set by zone. In “R-2,” a single-family zone that covers substantial areas of the city, for example, the lot has to be at least 5,000 square feet. Many older lots in Northwest cities including Tacoma are smaller than that. Furthermore, Tacoma specifies that an ADU must be on a lot that has a detached single-family house on it. The code is ambiguous, but it’s possible that the city means to ban installation of ADUs during construction of new single-family houses. Many cities do this: Bellevue, Washington, mandates a delay of three years between the completion of a house and the permitting of an ADU. But simultaneous construction is the smart, economical way to add ADUs, and it’s commonplace in some Cascadian communities such as Whistler, BC. There, as many as 75 percent of new single-family houses go on the market with ADUs already in them. In Tacoma, that pattern may be illegal.

Finally, Tacoma requires that the exterior design of ADUs match the houses they accompany—a harmless-sounding provision that turns out to be especially pernicious to ADUs’ affordability, as explained below.

Tacoma’s tale is not too different from the stories of most Cascadian cities: ADUs are legal but restricted to within an inch of their lives. You can construct the story for your city by studying the ADU Gauntlet. A speedier way to understand the gauntlet is to review the seven questions in the table, which reflect the main regulatory barriers to ADUs.

How Many ADUs Are Allowed Per Lot?

Until the 1980s and 1990s, many communities across Cascadia banned ADUs outright. Only Idaho Falls and Salem, Oregon, still do that, but Burnaby, BC, comes close: it allows secondary suites only for family members. The other 43 cities we reviewed allow ADUs, although seven of them—including Langley, BC, and Everett, Washington—permit in-home apartments but not detached units. Vancouver and Richmond, BC, lead the pack, by allowing two ADUs per single-family house: one indoors and one in the backyard. The suburban city of Nampa, Idaho, goes further still. It does not restrict the number of attached ADUs a house may hold and allows two detached units in addition. Yet, Nampa undoes all the benefits of this policy with a separate rule, which says that all ADUs on a site must be rented to the same party. How many households want to rent multiple units on the same site?

Across the region, the trend toward legalizing ADUs continues to inch ahead. Vancouver, BC, legalized in-home units in stages starting in the 1980s and finished the job in 2004, then allowed laneway houses in 2009. Most Washington cities legalized ADUs in the 1990s to comply with the state’s growth management act. Seattle did so in 1994, legalizing detached units in 2009, initially only in limited numbers and later without limits. Portland unlocked the door to ADUs in 1981, but it didn’t open the door until reforms in 1998.

How Many Off-street Parking Spaces Are Required per ADU?

Off-street parking requirements are nearly ubiquitous in municipal land-use codes. They’re a colossal impediment to compact communities. They’re mostly insane and counterproductive, if politically entrenched, and they will figure in future articles in this project. For now, just notice that one way a city can legalize ADUs but pinch their number is to require a complete, additional, off-street parking space for every in-law apartment or garden cottage. At many houses, especially those in dense, in-city districts where the demand for housing is strongest, installing another off-street parking space is expensive if not physically impossible. Look at the Street View of Kitsilano again (or think of an urban neighborhood you know well), pick a house, and try to figure out where you would put a pad of pavement at least eight feet wide and twenty feet long, plus connections to the street by a curb cut and driveway. What’s more, you cannot just put this pad anywhere. Many cities specify that all parking be beside or behind the house, not in front of it. Eli Spevak, a Portland mini-house developer, says, “Excessive parking requirements are the most common ‘poison pill’ included in many communities’ ADU regulations.”

Of the 46 Cascadian cities we reviewed, 36 require at least one additional off-street parking space per ADU in most or all cases. Two thirds of the people who live in these 46 cities are in parking-mandate cities. (Another 7 percent live in cities that do not allow, or barely allow, ADUs.) This sea of parking-pushing cities makes those few municipalities that break the pattern stand out like islands. This archipelago of sanity includes six outposts: Vancouver and Victoria, BC; Portland and Corvallis, Oregon; and Nampa and Meridian, Idaho. These places trust citizens to decide for themselves whether they want parking spaces with their accessory housing.

Must the Property Owner Live on the Site?

Another poison pill that many localities drop into their ADU rules is a requirement of owner occupancy: property owners must live on ADU sites, either in the primary or secondary unit. This rule gives bankers the jitters, which prevents many homeowners from securing home loans to finance the ADU construction. Owner occupancy sharply limits the value appraisers can assign to a house and ADU and makes the property less valuable as loan collateral. If a bank forecloses on a house and suite covered by an owner-occupancy rule, it cannot rent out both units.

Portland repealed its owner occupancy provision in 1998, but most other communities retain the rule. Some 30 of the 46 cities reviewed require owner occupancy, and Burnaby’s family-only rule is similarly restrictive. Only eight cities, which have only one third of the combined population of all the cities, have no such restriction: Vancouver, Richmond, and Victoria, BC; Portland, Bend, and Ashland, Oregon; Yakima, Washington; and Nampa, Idaho. (Two others ban ADUs outright, and five cities’ rules are unknown on the ADU Gauntlet table.)

How Many People May Live on the Lot?

Occupancy limits, which cities set to cap the number of nonrelated people who may share a dwelling, are confused, logic-less, and serve no legitimate public policy. Indeed, they are morally bankrupt: a way for privileged people to discriminate against people who are young, poor, or recent immigrants. Elsewhere, we’ve written thousands of words about them, encouraging all Cascadian cities to discard them. Five cities in our review of 46 have done so: Surrey and Victoria, BC; Bend, Milwaukie, and Tigard, Oregon. The others blend ADUs into the corrupt stew of occupancy limits, which just makes things weirder.

The normal legal home of occupancy limits is in cities’ official definitions of the words “household” (or “family”) and of “dwelling unit.” A household is a group of unlimited related people or some certain number of unrelated people who share a dwelling unit. A dwelling unit is usually described as a set of one or more rooms with a private entrance, a place for sleeping, a kitchen and a bathroom. By these definitions, all ADUs qualify as dwelling units, and therefore, in the absence of other rules, each ADU could hold a household. In 11 Cascadian cities, such as Vancouver, BC; Eugene, Oregon; and Kent, Washington, each ADU is just a dwelling unit: it gets its own occupancy quota. In 14 cities, including Portland, Seattle, and Spokane, though, it must share the primary house’s occupancy quota or remain within another tight occupancy constraint. (In another 14 cities, marked with question marks in the table, our review did not reveal clear occupancy rules. Many of these cities likely have so few ADUs that the issue may never have come up.)

How Big May ADUs Be?

Size limitations are complicated and varied, as a glance at the ADU Gauntlet shows, and complexity breeds creativity among developers. They stay within the letter of the law while still building what people will pay for. Vancouver, BC, bans laneway houses larger than 500 square feet but allows an additional 220-square-foot garage. Consequently, most laneway developers construct 720 square-foot units with “garages” that are actually living spaces—living spaces with heat-leaking garage doors.

Such unintended consequences are not the main problem with size caps, though. The main problem is that they block many ADUs from ever getting installed. For years, for example, Portland capped accessory units at the lesser of 800 square feet or one-third the floor space of the primary dwelling. In a 900 square-foot house (the US-average size of houses built in 1950), for example, an ADU could not exceed 300 square feet. The rule helped to keep ADU development at a trickle. Portland bumped the fraction up to three-fourths in 2009: A 900-square-foot house could now host a 675-square-foot cottage. For this reason, and because of some other reforms, ADU development more than quadrupled.

Portland, like many cities, also restricts cottages’ footprint. DADUs combined with other accessory structures on a lot, such as detached garages, may cover no more than 12.5 percent of the site. On a 5,000-square-foot lot with a 280-square-foot one-car garage and a 45-square-foot potting shed, a cottage would be limited to a meager 300 square-foot footprint.

Many communities tamp down ADUs by enforcing size caps like the one that Portland discarded. In 13 Cascadian cities—including Kent and Vancouver, Washington; Victoria and Surrey, BC; and Bend and Springfield, Oregon—ADUs may not exceed 40 percent (and in some cases 33 percent) of the floor area of the primary unit. In fact, the only city we surveyed that leaves size unregulated is Burnaby, BC, and why would Burnaby bother? It bans DADUs completely and only allows attached units for family members.

Where in the City Are ADUs Allowed?

All cities that allow ADUs constrain them by restricting what types of lots and buildings may hold or accompany them. Some cities are only mildly restrictive; others seem almost paranoid about secondary dwellings. Vancouver, BC, is among the most open. It welcomes secondary suites in houses and condominiums citywide, wherever layout permits. It allows laneway houses on 90 percent of single-family lots. Portland allows them not only at detached, single-family houses, but also at attached and manufactured homes.

On the other end of the scale are Yakima, Washington, and Ashland, Oregon. Yakima only allows accessory units on lots that spread over at least 10,890 square feet—a full quarter acre. No other city demands even close to that much land. Ashland, meanwhile, requires that every ADU get a “Conditional Use Permit.” Getting such a permit is typically so expensive and time consuming that many developers blanch and flee at the mention of the term.

Must DADUs Match House in Exterior Design?

Most cities require that the exterior appearance of backyard cottages and other DADUs match the primary house. Some 27 of the 37 cities that allow DADUs for which Sightline found data require that the smaller unit be a scale model of the house’s appearance in at least some of these ways: finish, roof pitch and materials, window proportions, color, trim, and siding. Only nine Cascadian cities, including Vancouver, BC; Seattle and Kent, Washington; Eugene, Oregon; and Nampa, Idaho, have no design standards. These nine cities hold only a third of the population of the 46 cities we surveyed.

Are design standards a weighty problem, though? They may sound like commonsense safeguards against tacky cottages. They are not. For starters, some homes aren’t worth matching. As Portland developer Eli Spevak puts it, with design standards, “Ugly house -> ugly ADU.” More insidiously, to make cottages that match the houses they sit behind, builders have to custom-build each one. That’s expensive, like buying your clothes from a tailor. The lack of design standards in Vancouver, BC, has allowed laneway developers to control costs by standardizing and prefabricating building components.

Adding Up

Beyond the seven criteria just reviewed, cities have still more requirements: where an ADU may be in a house or on a lot or with relation to the house or garage or lot lines; how tall it can be; where the door can be; how much of the front wall must be windows; whether it must have its own porch; the ratio of any second floor to the first floor; and more. Much more. Cities, especially in Oregon, also charge fees to ADU builders. Some of them are thousands of dollars. But the ADU Gauntlet at least captures the magnitude of the regulatory obstacle course that homeowners must run if they want to install an in-law apartment or laneway house. The gauntlet’s complexity threatens to overwhelm the mind. To simplify comparisons among cities, we’ve constructed a crude scale to score how welcoming cities are to accessory units.

For each of the seven criteria in the ADU Gauntlet, we assigned points on a scale of either 10 or 20 points. For example, legalizing both attached and detached ADUs earned Vancouver, BC, all 20 possible points in the “how many ADUs allowed” category. Seattle, which allows either an attached or a detached unit but not both, earned 10 points in this category. Salem, Oregon, which bans ADUs, earned 0 points. After following a similar logic for all cities and all criteria, we summed each city’s total. The top 25 cities by population are in the table below, in order of their score. (Further notes are at the bottom of the article, and scores for all 46 cities are also marked on the right side of the ADU Gauntet.

| How ADU-friendly are Cascadia’s biggest 25 cities? | Score (0-100) |

| Vancouver, BC | 96 |

| Portland, OR | 72 |

| Richmond, BC | 70 |

| Nampa, ID | 67 |

| Victoria, BC | 60 |

| Seattle, WA | 58 |

| Eugene, OR | 56 |

| Kent, WA | 53 |

| Gresham, OR | 49 |

| Surrey, BC | 47 |

| Yakima, WA | 45 |

| Boise, ID | 43 |

| Hillsboro, OR | 43 |

| Spokane, WA | 41 |

| Beaverton, OR | 39 |

| Bellevue, WA | 39 |

| Langley, BC | 38 |

| Vancouver, WA | 38 |

| Tacoma, WA | 38 |

| North Vancouver, BC | 38 |

| Burnaby, BC | 36 |

| Everett, WA | 29 |

| Abbotsford, BC | 28 |

| Coquitlam, BC | 22 |

| Salem, OR | 0 |

Because of the imprecision of scoring and weighting cities on each criterion, scores close to each other are unlikely to be reliable reflectors of substantial differences. But big differences on the score likely tell the truth. Vancouver, BC, is by far the most welcoming place in Cascadia for ADUs. It is alone atop the league. Portland, its closest competitor, is 24 points below it. Seattle lags by 14 points more, and smaller cities trail away down to no-ADU Salem. These lagging scores reflect a main reason that ADUs remain so scarce in most of Cascadia and why Vancouver, BC, has so many more of them.

Not a Secondary Issue

The gauntlet of rules that keep accessory apartments and cottages so rare are not a small-time concern. They are a first-order priority for Cascadia’s cities. The overwhelming majority of the region’s residential land is restricted by city zoning codes for single-family homes and nothing else. These rules are among the urban laws that do the most to keep housing prices unaffordable, cities sprawling, and carbon emissions voluminous. The politics of upzoning are almost never favorable: single-family neighborhoods fight fiercely against even duplexes, much less larger, multifamily buildings.

Yet for the Northwest, the only path of urban development that can lead to affordability and climate- and energy-security—not to mention that can adapt the 7 million detached houses already built across the region for shrinking households and aging populations—is to open up single-family neighborhoods to more residents. Accessory dwelling units are the main politically plausible way to do that, though decriminalizing rooming houses and roommates can help.

During World War II, housing for military-industry workers precipitated widespread subdivisions of houses in Portland and in Vancouver, BC. Neighborhoods full of one-household-per-lot dwellings became neighborhoods full of dwellings split among two or three households. War mobilization swept aside local opposition. After the war, most of these neighborhoods and houses reverted to their single-family norm. The gathering trend of ADU legalization and development across the Northwest promises to repeat and make permanent that brief war-time period.

Unfortunately, citizens have yet to convey to city halls that rising to housing and climate challenges warrants the kinds of sweeping changes witnessed during the 1940s. And the politics of zoning reforms are doubly hamstrung. First, as argued previously, classist attitudes and financial self-interest have long motivated a potent coalition against renters in single-family zones. There’s a quote passed around among planners in the Northwest, often repeated with a smirk. It’s an exaggeration, but it’s not a lie: “In India, they have the caste system. In England, they have the class system. Here, we have zoning.”

That’s why Kitsilano is such an important example: the density is there, but it’s mostly invisible, hidden in a landscape of classic Northwest bungalows. ADUs provide density that do not trigger class opposition in the same way that the words “duplex” or “apartment building” do.

Second, and as important, local land-use regulations—the home of ADU restrictions—are arcane, technical, and bewilderingly complicated. They seem mundane, boring, and unlikely to matter much in the grand scheme of things. Yet their ultimate implications are momentous: the global climate is at stake, for example, as are housing market chains of cause and effect that ultimately yield rates of homelessness. Thus, in a mild, urban-planning-kind-of-way, ADU restrictions offer a small instance of what Hannah Arendt famously called the banality of evil.

More hopefully, their very banality may offer an opportunity for progress on legalizing ADUs. Citizens, planners, and elected leaders in cities across Cascadia can target for relaxation the rules documented in this article—the rules that stem backyard cottages and forestall in-law apartments—and perhaps they’ll find that all of Cascadia is now ready to shrug and accept Kitsilano-like density. Perhaps the whole region in 2013 is like Vancouver, BC, was in 2004, when the city council proposed to legalize ADUs citywide, and hardly anyone even showed up for the hearing. Perhaps we’re ready to again accept such a commonsense, affordable and time-honored way to live.

NOTES on ADU SCORES: In several categories, scoring cities’ policies was straightforward. For example, not requiring a parking space yielded a score of 10, while requiring one produced a score of 0. Owner occupancy requirements and design standards were also simple to score, because cities mostly either have or do not have these rules: No occupancy or design rules earned 10 points. Roommate caps, size limits, and where ADUs may be in a city were more difficult to score. We attempted to set the best city in the region as the top of the scoring range and the worst as 0. Then, we used arithmetic and judgment to distribute the cities across this spectrum, in proportion to the stringency of their ADU restrictions. Because many rules are incommensurable, this process was necessarily inexact. For cells in the table marked with a question mark, we assigned 0 points: Bellevue and Abbotsford may therefore deserve at most 10 points more than we awarded. Coquitlam may deserve at most 20 additional points.

THANKS: “Researching restrictions on accessory dwelling units in Northwest cities is like being a character in a Franz Kafka novel,” I posted on Facebook part way through preparing this article. “Writing them was, too,” replied former Seattle Mayor Greg Nickels. I share credit with several people who helped me map the Kafka-esque labyrinths of municipal rules in this article and the two that preceded it: Sightline staffer Mieko Van Kirk and Sightline Writing Fellow Alyse Nelson; in Portland, ADU builder and expert Eli Spevak of OrangeSplot; real-estate tracker and aspiring ADU developer Martin Brown of AccessoryDwellings.org; Jordan Palmeri and his collaborators at the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality’s Green Building Team, who did much of the work on the ADU Gauntlet table; and more than a dozen city planners in many Northwest cities who patiently explained their rules to us.

Comments are closed.