From sunny Southern California, some gloomy news on highway tolls. Here’s the Orange County Register…

Orange County’s toll roads have slid farther and farther behind the confident projections of ridership and revenue on which they were built, prompting an unusual state review of their finances.

The roads were the first of their kind in California, a bet that drivers would be willing to pay to escape the grind of Southern California freeway traffic…but the bet has not paid off as well as operators expected.

The bonds backing both projects have sunk to junk status—a sign that investors are worried about whether they’ll actually be paid back.

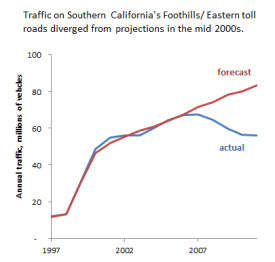

To be fair, one of the two toll projects was performing as expected up until 2006—when traffic started falling below projections. Revenue stayed up with projections for another couple of years, before it started to trail off as well.

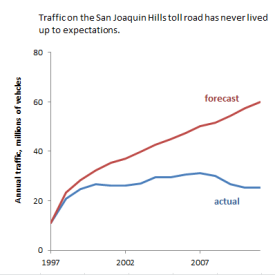

But traffic on the other route lagged behind forecasts from the get-go. The toll route is generally free-flowing, but drivers prefer parallel, toll-free alternatives, even if they’re clogged with traffic.

Toll road failures are nothing new; in fact, they’re surprisingly common. But I thought that this case deserved a special mention, for two reasons.

First, it took about a decade for the forecasting flaws in the Foothills/Eastern projections to appear—but those flaws quickly turned high-grade bonds into junk. The lesson here: in highway bonding, short-term success doesn’t matter that much. To be safe from serious fiscal consequences, you have to be right over the long haul.

And second, there are very relevant connections between the Southern California roads and what’s happening here to the Pacific Northwest. The traffic forecasts for the Southern California roads were made by the same consulting firm—CDM Smith, formerly Wilbur Smith—that performed the investment-grade bond study for Washington’s SR-520. And that firm was recently contracted for similar study on the Columbia River Crossing connecting Portland, OR with Vancouver, WA. CDM Smith has a good reputation—but that didn’t protect them from producing projections that went badly awry. For SR-520 or the Columbia River Crossing to avoid the same fate as the California toll roads, they’ll have to meet CDM’s traffic growth forecasts not just for a few years, but for many years to come.

What’s more, the troubles facing Southern California’s toll roads may have ripple effects in the municipal markets here as well. Bond investors are notoriously risk-averse. The savvy ones may look at the California toll road failures, along with many others, and decide that there’s a lot more risk in road-tolling bonds than they thought. If that happens, the Northwest might be faced with higher interest payments for transportation bonds, and lower revenues from the bond markets—neither of which is good news for boosters of highway megaprojects.

Comments are closed.