Sightline is an unapologetic booster of British Columbia’s carbon tax. For good reason, other jurisdictions look to Canada’s west coast as a model of a strong carbon policy. Yet, BC’s tax is not perfect. It’s come in for criticism from progressive groups in BC who wish the tax were fairer, stronger, and broader than it is now.

Let’s take a moment to examine three major criticisms of the tax. Then we’ll recommend some fixes that can make BC’s tax even better.

Robin Hood in Reverse?

The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA) has been shining a spotlight on the tax’s economic fairness since it was first proposed in 2007. It’s an important perspective because consumption taxes, particularly on energy, are often regressive. Let’s take a look at how the tax stacks up.

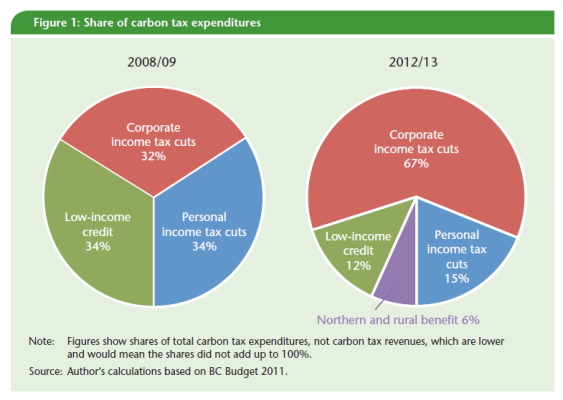

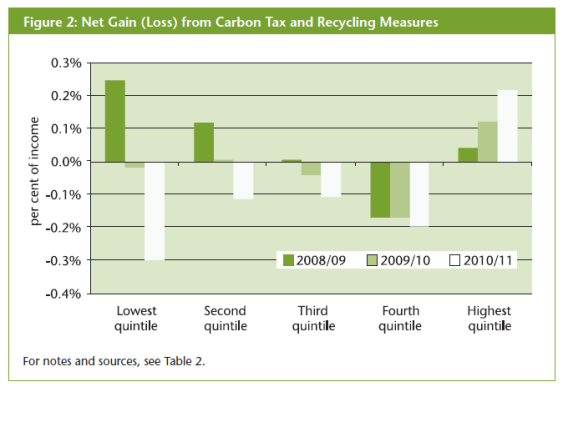

BC carbon tax has attempted to address concerns about fairness by funding a special low-income tax credit designed to offset the disproportionate impacts on low-income families. But the emphasis on these fairness-enhancing low-income tax cuts has diminished drastically since 2008. In its first year, according to CCPA’s “Fair and Effective Carbon Pricing: Lessons from BC,” the low-income tax credit accounted for fully 34 percent of the tax revenue, but by 2012 it had fallen to only 12 percent of overall revenue. Every year, more of the revenue has been directed toward corporate and business tax cuts, which tend to benefit the wealthiest individuals.

According to another report by CCPA, “Is BC’s Carbon Tax Fair?,” the tax was slightly progressive for the first year, but since then it has become increasingly regressive.

Overall, the carbon tax rate has increased 200 percent since it started in 2008—from $10 to $30 per ton—yet the total revenue dedicated to the low-income credit has grown by only 15.5 percent. In 2012, the lowest-earning 20 percent of BC families will lose $47 per year as a result of the tax, while the top 20 percent will gain $311.

CCPA argues that the tax structure should be re-evaluated to make it more equitable, with between one-third and one-half of the revenue used for low-income tax credits. They also suggest making the low-income tax credit rise proportionately to the carbon tax. Fortunately for carbon tax proponents, CCPA’s equity-enhancing tweaks would be easy to implement and they would make the tax much fairer to BC’s residents.

Keeping the Tax on Pace with Targets

The carbon tax has also come under fire from environmentally focused organizations such as the Pembina Institute and the Sierra Club of BC for not doing enough to combat climate change. Green advocates have criticized both the scale and scope of the carbon tax.

The Pembina Institute, a Canadian sustainable energy think tank, argues in their suggestions for the BC carbon tax review that the tax rate is not high enough to keep the province’s emissions reductions on track. While carbon tax rates were apparently sufficient, in tandem with other carbon-reduction strategies, to reduce emissions enough to meet BC’s 2012 emissions reductions target, the targets for 2016 and 2020 aim for much greater emissions reductions but with no corresponding increase in the carbon tax rate, which is currently stalled at $30 per ton. Pembina suggests that the tax will need to increase to between $100 and $200 per ton by 2020 to keep pace with BC’s emissions goals.

Expanding the Tax in More Ways than One

Others argue that the carbon tax is not extensive enough. While the provincial government has claimed a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions of 4.5 percent (about 3 million metric tons) since 2007, the official tally excludes several important categories of emissions.

The carbon tax applies to only about 75 percent of all the emissions that occur within BC. It covers fossil fuels that are combusted within the province, but not the emissions from harder-to-capture activities like logging and landfill waste. Yet, according to the Pembina Institute, an additional 7 percent of BC’s emissions can be accurately measured, mostly in the “process” emissions from natural gas extraction, plus lime and cement production. Pembina argues these measurable emissions sources should face the same tax treatment as the fossil fuel emissions already under the tax.

What’s more, as the Sierra Club of BC points out in its recent “Emissions Impossible” report, the carbon tax overlooks emissions from BC’s prodigious export of coal, oil, or natural gas. If all of these excluded sources were counted—including emissions from BC forest lands—the Sierra Club argues that the province’s carbon footprint would be four times higher than the officially reported 62 million tons. Counting all of these categories BC has notched a greenhouse gas reduction of only 1 percent since the carbon tax went into effect in 2008—hardly a huge success.

To be clear, neither the Pembina nor Sierra Club arguments undermine the case for carbon taxes. They simply show that the tax is not applied widely enough.

Fixing the Tax

BC’s carbon tax is a success, but it is not perfect. Fortunately, most of its major imperfections are fixable.

Let’s start with the easiest fix first. The BC government should adopt CCPA’s equity-enhancing tweak—expanding the low-income tax credits—to make the tax fairer to BC’s residents. It would be easy to implement, and it would help make the tax an even better model for other jurisdictions.

A second fix would adjust the tax rate. The carbon tax reached its final scheduled increase, to $30 per ton, in July 2012. To help achieve greater emissions reductions going forward, the government can continue the tax’s annual $5 increase, stepping up to $35 next summer and growing in the future. A steady annual increase of $5 would almost reach $70 per ton by 2020, not quite Pembina’s optimal rate of $100 to $200, but it would provide a clear market signal and steady pressure on carbon emissions. The province need not settle on an ultimate price now, but should continue to review its carbon reduction progress regularly and evaluate whether higher tax rates are in order.

Finally, the province should seriously evaluate expanding the scope of the tax. Applying the tax only to fossil fuels has some notable advantages, such as minimizing the administrative complexity of the program. But if other forms of emissions can be reliably monitored and priced, such as the additional 7 percent identified by the Pembina Institute, they should eventually be folded into the scope of the tax.

Perhaps most importantly, BC should begin aligning its green reputation with its role as a seller in the global fossil fuel economy. To be fair, the government’s official tally of greenhouse gases—including internal emissions but excluding exports—is consistent with international standards for reporting emissions, yet BC’s tally badly distorts the province’s true contribution to climate change. A more accurate and credible accounting would at least report on BC’s total carbon contribution, including exports, and officials should begin phasing in a carbon tax on the carbon-based fuels that it exports.

So far, BC’s carbon tax has correlated with emissions reductions and no loss in economic dynamism. That’s good news. Better yet, the tax’s imperfections can be fixed in ways that will make it an even stronger model for other places.

Comments are closed.