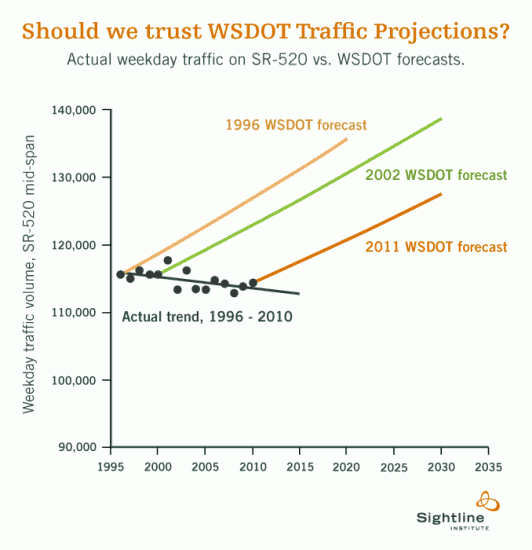

I’ve been harping for a while now on the laughably inaccurate traffic forecasts by Northwest transportation agencies. See, for example, the following chart, which shows how WSDOT’s predictions of ever-growing traffic on the SR-520 bridge have lined up with reality:

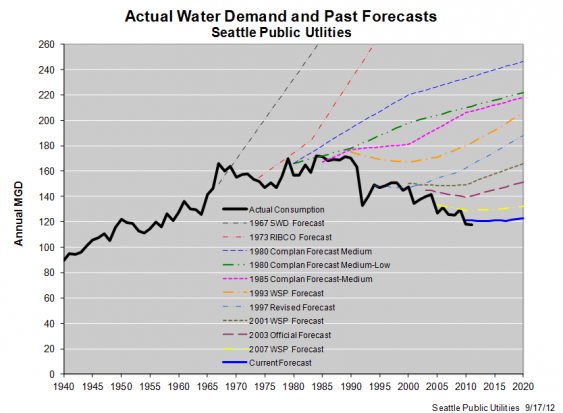

But as an alert reader points out, traffic isn’t the only domain where forecasters persistently overestimate future demand. Seattle’s utility department has done the exact same thing for water consumption for more than four decades. (Click the image for a larger version.)

Of course, this chart is actually published by Seattle Public Utilities itself—making this chart a forthright and refreshingly clear-eyed admission of the agency’s own forecasting errors.

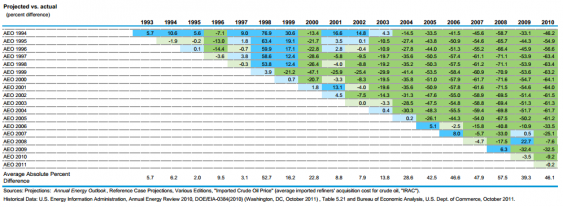

In the same vein, the US Energy Information Administration recently published a review of its own forecasting record—and, like Seattle Public Utilities, it found massive forecasting inaccuracies. The chart below is just one example. It’s a bit hard to read (click on it for a larger version!) but in a nutshell, the sea of green represents years and years in which actual oil prices were significantly higher than EIA forecasts—suggesting a persistent bias that has clouded the agency’s vision since about 1999.

I’m truly not trying to pick on Seattle’s water agency, or on the Energy Information Administration. Far from it! The fact that both agencies have been willing to evaluate their track records, and share the results with the public, strikes me as both thoughtful and refreshingly candid.

But such clear-eyed self-evaluation by forecasters is far from universal; some prognosticators never bother to look backwards. Author and forecasting guru Nate Silver spoke about the problem in a recent interview at Talking Points Memo:

You write in [your new] book about forecasters’ biases and the hurdles to making objective predictions. How can forecasters overcome that bias?

In the long run, the best test is: How do your predictions do? People are sometimes too slow to change course when they’re clearly doing something wrong…I see prediction as the means by which we test our theories against reality, test are we being objective, are we in touch with reality? I mean that fairly literally. If you keep making these statements that are totally and completely wrong…then you have to examine your world view, and say, “Am I remotely in touch with what’s really happening?” People don’t like to change, they don’t like to admit faults…

That seems exactly right to me. Taking the time to check predictions against reality ought to be a regular habit among professional forecasters. Yet it’s surprisingly rare—which makes the self-examination by the EIA and Seattle Public Utilities all the more commendable.

I can only hope that the Northwest’s transportation forecasters follow their lead.

P.S. Nate Silver’s book has gotten many glowing reviews, but also some sharp criticism for his views on climate science.

Comments are closed.