Here’s an oldie but a goody: a 2009 Brookings report on sustainable transportation in Germany. The upshot is that Germans enjoy a safer, more energy efficient, and more affordable transportation system than Americans do. (Germany almost certainly beats Canada too, though the article focuses on the US.)

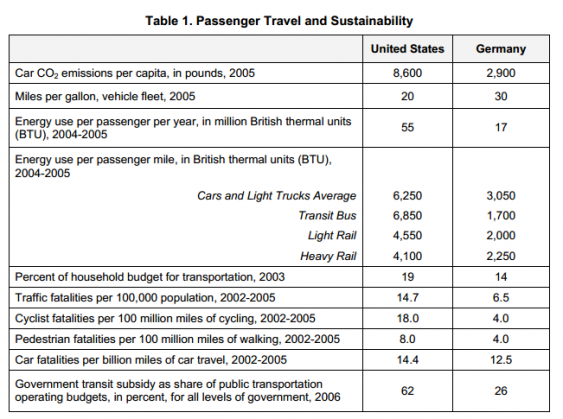

Just look at the numbers: compared with the US, Germany’s cars emit 1/3 the CO2 emissions per person, and cause less than half as many traffic deaths. And it’s a safer place for bicyclists, with a quarter the US fatality rate for cyclists, after adjusting for the number of miles biked. And even though Germans take transit far more frequently than do Americans, government subsidies account for only 26 percent of transit agencies’ budgets in Germany, compared with 62 percent in the US.

The question is: why? What gives Germany the edge?

The article presents a nice summary of the major policy differences that have helped move Germany into the forefront of sustainable transportation within the developed world. Standing head and shoulders above the rest is the high cost of driving—gas taxes, vehicle sales taxes, car registration, and drivers licensing are all more expensive in Germany than in the US. As of 2006, gas taxes averaged 42 cents per gallon in the US; in Germany, they were $3.60.

Paradoxically, though, the high cost of driving doesn’t make transportation as a whole more expensive. Although Germans still take 60 percent of their trips inside a car or light truck, the trips tend to be shorter, and they’re in more efficient vehicles. And more households find that they can make do without a car, or with only one car per household instead of two or more. As a result, Germans spend 14 percent of their overall household budgets on transportation, compared with 19 percent in the US. This is an example of how regressive taxes (i.e., gas taxes) can sometimes lead to progressive end results (i.e., more transportation options and lower household spending on transportation).

The Brookings article lists a host of additional policy differences that separate Germany and the US: lower speed limits in cities; car-free zones in downtowns; annual vehicle registration fees tuned to engine size and emissions; coordinated transit, bike, and pedestrian planning; and land-use planning that favors (or at least doesn’t prohibit) higher-density housing near already-developed areas.

I’d argue that there’s one factor that the article misses: history. Germany’s major urban cores were all fully developed well before the rise of the automobile—in eras when walking, horses, and maybe transit were the common means of transportation. As a result, there’s just not a lot of room for cars in most of the major German cities. Car-oriented development is inherently spread out, because cars require lots of room for both streets and parking; and the fact that Germany’s major urban areas were already densely built out in the 1950s made them harder to retrofit for the car. In contrast, many US urban areas, particularly in the West and South, were just taking off in the 1950s. Older US cities (New York, Boston, Philadelphia, DC) are less car dependent than many of the cities that boomed in the last 60 years (Atlanta, LA, and, yes, Portland and Seattle). History gives these older places a real edge in sustainable transportation—not only because of smart transportation policies in the present, but because of decisions made for unrelated reasons decades or even centuries ago.

Comments are closed.