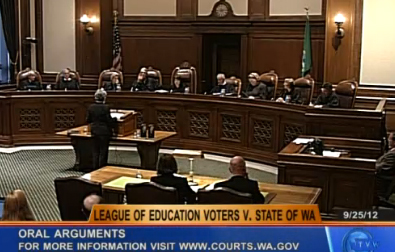

As I’ve said, yesterday was a hugely important day: the Washington State Supreme Court heard oral arguments on I-1053, the undemocratic law that gives minority factions in each house of the Washington legislature veto power over closing tax loopholes and raising revenue. (Find news coverage at Publicola here and here, The Oregonian, and The News Tribune.) This is arguably the single biggest legal barrier to progress in Washington on issues ranging from climate to education.

I watched the hearings twice (here) and took note of every question a justice asked. I even tried to study the justices’ inflection and body language. (Paging, Cal Lightman.)

I came away more optimistic than before. I’m raising my estimate of the odds from one in four to one in two—50-50—that the court will throw out Eyman’s measure and restore the Washington legislature to majority rule. If so, many good things will become more possible: Puget Sound clean-up, funding for education, perhaps even a carbon tax shift. Such a ruling would also moot I-1185, a carbon copy of 1053 that will be on November’s ballot.

But handicapping supreme court cases is notoriously difficult, and I’m a novice at it. So you should take what follows with a handful of salt. We won’t know the outcome until the court announces its decision, probably some time before the end of the year.

Every member of the court asked at least one question of the attorneys. Questions of the pro-supermajority attorney, Solicitor General Maureen Hart from the state attorney general’s office, came from more justices, more aggressively, and with sharper legal edges. Two justices posed questions that almost mocked Hart’s argument. Justice Debra Stephens asked whether a statute that required new laws to be approved not only by the legislature and governor but also by “Joe Smith of Walla Walla, Washington” would be constitutional. Justice Tom Chambers asked the same about an initiative that set a 90 percent supermajority requirement in the legislature and also required Santa Claus’s signature. That question should have given 1053 sponsor Tim Eyman and the oil and liquor lobbies a belly ache.

Other questions and comments verged on incredulous. Justice Steve Gonzalez asked, “However does one get standing . . . ?”—not “how does” but “however does.” Justice Stephens interrupted Hart to interject, with passion, “You’re losing me there. I just don’t follow that at all.” Chief Justice Barbara Madsen broke in at another point with, “That assumes that the legislature wants to violate what it thinks is the law.” Later, she said, “It seems odd to me that you’re saying that.” And Justice Susan Owens concluded a skeptical string of questions by saying, “Those are two really big presumptions.”

All of this was in response to Hart’s curiously inverted argument—which is essential to winning a dismissal of the case—that the legislature isn’t actually governed by 1053’s supermajority requirement. The legislature may, she said, ignore the law and operate by simple majority. Then, if it passes a tax or closes a tax loophole and someone challenges that law, the court could properly rule on the constitutionality of 1053. I’ve argued for the legislature to do just that, but I know it would be a violation of legislators’ oath of office along with a bevy of parliamentary rules and precedents, plus a whole slew of legislative traditions. It’s strange to hear the attorney general’s representative strenuously insisting that the law it is defending can be ignored by the legislature it is intended to govern.

Justices James Johnson and Charles Johnson asked friendly questions of Hart. The former, who in previous life helped Tim Eyman draft initiatives, didn’t just ask friendly questions. He essentially argued from the bench in support of 1053.

The tables reversed when Paul Lawrence, attorney for the majority-rule side, stood to make his case. He was questioned repeatedly, aggressively, and at some length by Justice James Johnson. Justice Charles Johnson also threw a couple of odd, quasi-political questions at him. Others mostly asked questions that were friendly or neutral. The one exception was Justice Debra Stephens, who posed a hard, legal question.

It’s always been unlikely that the court would overturn the initiative, because of the numerous legal hurdles that plaintiffs have to get over. On the central question, the state constitution is clear: majority rule, no vetoes for minority factions. But before the court gets to that question, it first must answer “yes” to a series of procedural questions. On three previous occasions, it has said “no” to at least one of those preliminary questions. Most recently, the court dismissed a challenge to supermajority requirements in 2009. In that decision, Justice Mary Fairhurst wrote for the court and every current justice who was then on the court concurred: Tom Chambers, Charles Johnson, James Johnson, Barbara Madsen, Susan Owens, and Debra Stephens. So we know that even those who seemed unfriendly to minority rule in yesterday’s hearing have in the past voted to leave it in place.

Bearing all of this in mind, I’ll go out on a limb and guess the votes: I count Justices Mary Fairhurst, Susan Owens, and Charlie Wiggins as ready to throw out 1053 in this case. Justices Tom Chambers, Steve Gonzalez, and Barbara Madsen are harder to read, but I think they’re leaning the same way. Justice Debra Stephens is undecided for procedural reasons. She is sure supermajority requirements are unconstitutional, but she’s not sure this case is properly before this court. The two Justices Johnson believe not only that minority rule is constitutional but that the case isn’t properly before the court. If I’m right, that’s six or seven to two, and majority rule will be restored in Olympia.

But, as I said before, I may not be right. This whole article is an exercise in guesswork. Supreme court justices ask questions for a variety of reasons. They may want other justices to hear the answer, or just the question. They may want those who helped them win office to see them asking the question. They may want to help an attorney who is arguing before them more effectively make the case. They may want to use up the time of an attorney arguing against their position. Only infrequently—exceedingly infrequently—do they ask questions in order to reveal how they will vote. So this entire exercise is fraught.

Still, I’m taking some hope from yesterday. The court may well throw out minority rule, which would be a cause for dancing in the streets.

But even if it does not, at least legislators now have a thorough legal brief from the attorney general advising them that 1053’s supermajority voting requirement does not, in fact, actually apply to them. Sure, supermajority is the “law,” reasons the attorney general, but don’t let that stand in your way: you’ve got every right to operate by majority rule, regardless of what the “law” says. If someone has a problem with that, they can sue you. And then the supreme court will have no choice but to decide what the constitution means when it says “majority.” It wouldn’t be a bad consolation prize.