I stopped buying new stuff for all of 2012 as an experiment to save money, cut clutter, and reduce my family’s carbon footprint. I also thought of it as a way to “occupy my wallet”—by which I meant I’d feel a tiny bit better keeping my personal pittance out of the hands of big corporations. What I didn’t think about was modern-day slavery.

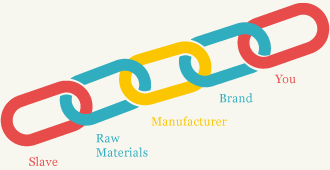

It turns out our stuff can also have a “slavery footprint.”

Stephanie Hanes—who recently wrote about how many slaves it takes to produce her toddler’s necessities and possessions for the Christian Science Monitor—points out that most of us have “only a fuzzy idea about the forced labor and human trafficking that exists around the globe. We don’t often think about our hand in supporting it.”

I had some idea about ugly practices in the production of electronics and diamonds. But like Hanes, I was shocked to learn that stuff for kids (I’ve got one of those.) accounts for a surprising share of what experts refer to as modern day slave labor—toys, clothes, diapers, even baby cereal and soap. Also noteworthy for Sightline audiences—if you didn’t hate coal enough already—is that coal industries around the world are some pretty bad offenders in terms of forced and child labor.

Working on a story about sex trafficking, Hanes came across a US State Department website where you can calculate your “slavery footprint.”

I recommend doing it. You answer a battery of questions about your lifestyle—what your house looks like, what’s in your medicine cabinet, your jewelery box, and your closet, the electronics you own, what you eat—and, put bluntly, you find out the number of slaves you use. (The shock value of this wording is intentional, I think. And it does get your attention!)

Of the estimated 27 million slaves worldwide, Hanes “uses” 47, and her toddler accounted for 20 of those. (As she points out, news stories over the past couple of years have reported about the child labor behind some of American kids’ most popular brands, such as Mattel, Fisher-Price, and Disney.)

My own “slave count” came out to 40. And that’s only when I didn’t include the clothes and other items that I’ve purchased second-hand, so it may not represent a full reckoning. (There’s got to be at least some benefit from buying used…but it certainly doesn’t negate the problem).

According to the site, the bulk of the forced labor I support happens in China, where “coal mines, brick kilns and factories in the poorest regions…operate illegally, using much of China’s estimated 150 million internal migrants as slaves.” And in India, where “millions from… lower castes are enslaved in brick kilns, rice mills, and embroidery factories.” But the slave labor I’m responsible for comes from a handful of other countries too.

A US Department of Labor, Bureau of International Labor Affairs (ILAB) issues an annual list of the top dozen or so products likely to be made by child or forced labor. Agricultural goods, manufactured goods, and mined or quarried goods are the biggest offenders. Some things I consume on a regular basis—coffee, cocoa, cotton, rice—as well as energy from coal, which I’d rather not have anything to do with, make for a sobering list.

Far more sobering are the descriptions and images of little kids working under harsh and dangerous conditions. When it comes to coal, the majority of child labor is found in small-scale, artisanal mines. And, as ILAB points out, though the number of children working in mining is not as high as in other industries, it arguably represents the most dangerous occupation for children. Child workers in mining suffer a higher fatal injury rate than children in any other sector.

We westerners may not contribute to the coal problem in other countries directly, though coal power probably fuels the manufacture of other goods we do consume here. And schemes to export coal out of the US play into the global politics of and markets for coal, likely affecting labor issues in ways we can’t predict.

In the end, it’s all part of the same big problem of turning a blind eye to lacking or ignored labor standards in countries with which we do business.

So, how many slaves work for you? (Find out). And what do you do about it?

Anyone can be a more conscientious and informed consumer. But there’s also an app for that. With the Slavery Footprint app you can check in at stores and pressure brands about slavery in their supply chain as you shop. You can ask companies where their raw materials are coming from. And then, of course, you share your check-ins so your friends will get the word too.

In addition, the Slavery Footprint project gives you a range of actions to take upon calculating your score, including lobbying, volunteering, recruiting your friends. You can also get involved with organizations working to stop slavery around the world; Free the Slaves is one. I’m not up on this stuff, but I’m sure there are plenty of others.

But as Stephanie Hanes concludes—and I concur—all of that is very important and necessary, but “another, perhaps healthier, reaction to the slavery footprint is to simply have less stuff.”

She writes: “The world’s system of forced labor, slavery, debt bondage, trafficking—all of these human rights abuses that involve the desperate living and work conditions of others––goes hand in hand with Americans’ desire to consume. A pattern of consumption, I might add, that studies have shown does us very little good.”

And, I argue, buying less is liberating on all kind of fronts.

Comments are closed.