Brookings has released a new survey that shows American public understanding of climate science is rebounding.

When Brookings asked Americans if the earth’s climate was warming in 2008, 72 percent of Americans said “yes.” By 2010 the number had sunk to a low 52 percent—and it stayed in the 50s for several years. Today it’s back up to 65 percent.

Not too shabby—especially as it reinforces a trend seen in other polling (see here, here, and here.)

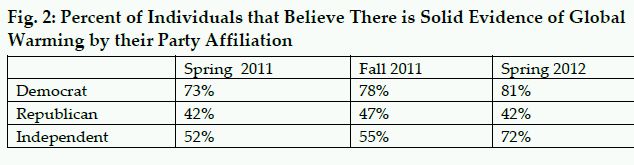

The partisan divide is still alive and well. But, quite significantly, independents have moved in the direction of hard climate evidence by a whopping 20 points in just a year—from 52 to 72 percent. As Joe Romm points out, this move toward science by independents, the solidified stance among Dems, and the marked stagnation among Republicans adds up to make climate a winning wedge issue.

Here’s a snapshot:

Also notable is that just under two thirds (63 percent) of those on the correct side of climate science say that they are “very confident” in their position—14 percentage points higher than in the fall of 2011 and the highest level since Brookings started their climate polling in 2008.

But, as Kevin Drum cautions (and all us climate communicators know this in our bones already), the swing might not be happening for the reasons you think it is or hope it would be. In other words, it’s the weather, not more scientific evidence:

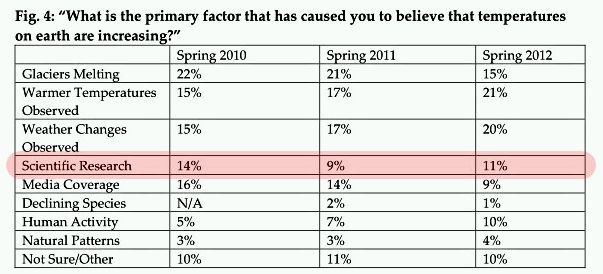

It would be nice to think that people are being swayed by the increasing torrent of scientific evidence about climate change, but it ain’t so. As the table below shows, only 11% of respondents say that scientific research is the main reason for belief in climate change. The most popular reason by far is personal observations of weather and warmer temperatures. And in a followup question, 68% of respondents said recent mild winters have had a large effect on their views.

Joe Romm put it this way: “Certainly the American public is seeing for themselves the off-the-chart heat waves and other extreme weather that climate scientists have long said would become more common as we pour more heat-trapping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere (see NOAA Chief: US Record of a Dozen Billion-Dollar Weather Disasters in One Year Is “a Harbinger of Things to Come”).”

And so it seems:

What are the takeaways?

Romm’s advice: “People are starting to connect the dots. Now if only policymakers can start doing the same…and seize on this winning issue.”

Drum’s advice: “…stop nattering on about the latest research. It may gall us to do it, but anecdotal evidence (mild winters, big hurricanes, wildfires, etc.) is probably our best bet. We should milk it for everything it’s worth.”

My advice: In plain language and in the simplest of terms, talk about extreme weather as a means to a frank, open, and honest conversation about climate impacts—and solutions.

Comments are closed.