Anyone familiar with Seattle’s Rainier Valley knows it’s a place in transition.

Long one of the most racially diverse neighborhoods in the Northwest, it has for many decades struggled economically. In recent years, some areas of the valley such as Columbia City have gentrified rapidly even while nearby neighborhoods were rocked by the economic downturn, experiencing high rates of foreclosure and unemployment.

It was in that complicated geography that the Puget Sound’s first light rail line arrived, bringing with it both the promise of new investment and, for some, the threat of economic dislocation. To evaluate the changes Puget Sound Sage just published a new report: Transit Oriented Development That’s Healthy, Green, and Just.

I highly recommend it, in large part because the report invites a valuable equity perspective into a conversation that has not often focused on social justice. I also recommend it because it’s well-grounded in data and research.

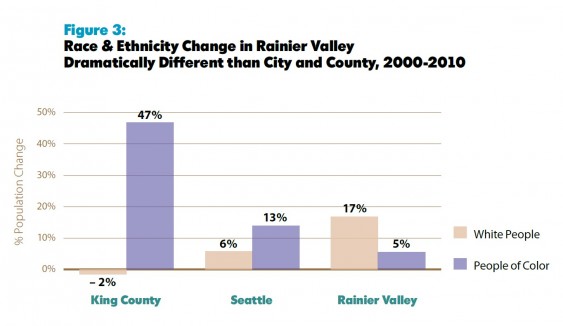

I even learned a few things, such as this fascinating demographic comparison:

The new light rail line is, of course, hardly the sole driver of change in the Rainier Valley, but it serves as a useful orientation because it is particularly tangible, recent, and significant.

Puget Sound Sage finds that like most large infrastructure investments, light rail has increased property values and raised rents. Now whether that’s a problem for you or not depends in large measure on what your own economic situation is like. For the 44 percent of the neighborhood’s residents who rent, it’s potentially a threat.

On the other hand, large-scale transit investments like light rail also bring with them a number of positive developments, such as increased private sector investment, renewed public sector interest, and economic activity. And all of that provides some opportunity to make the outcomes of transit oriented development more equitable, but only with proper policy guidance.

The central public policy question—and one that Puget Sound Sage frames up admirably—is whether the benefits of light rail and transit oriented development actually accrue to the specific people who live in the neighborhood. No doubt for many locals, gentrification may prove to be a very good thing. But for others, there’s strong evidence that higher housing costs lead to financial distress and displacement which, as the report shows, may undermine the benefits for the transit investment in the first place.

It’s not a simple problem and, as such, it’s not a simple thing to fix. The report outlines a number of principals and specific solutions—including applying a racial justice framework to transit oriented development planning—but I won’t spoil those for readers now. You should go read the full report. It’s worth it.

Comments are closed.