At this point, most serious researchers agree that the average city-dweller produces fewer climate-warming emissions than a typical suburban or rural resident. City-folks tend to drive less, and walk or use transit more, than those of us who live in suburbs or out in the country. And city dwellers also tend to have less living space per capita, and are more likely to share walls or ceilings with their neighbors—all of which tend to reduce energy consumption per person. (And just to be clear: there’s no finger-pointing intended here, since my own neighborhood easily qualifies as suburban!)

The connection between urban form and greenhouse gases is strong enough that many policymakers concerned about climate change are looking for ways to trim back on rural development, in exchange for a little more housing in city and town centers.

A little while ago, at the request of King County (which contains Seattle and its closest suburbs), Sightline took a look at one increasingly popular mechanism for doing just that: Transfer of Development Rights, or TDR. In a nutshell, TDR programs allow willing owners of rural lands to sell their development rights—which means that the rural lands will remain rural. In turn, landowners in areas where the county wants to encourage development can purchase those rights, and thereby gain the right to boost housing intensity to higher levels than local zoning rules would ordinarily allow. At their best, TDRs are a winner all the way around: rural landowners get some income for protecting their land; purchasers get a financial boost from higher development intensity; farmland or open space gets spared from development; and taxpayers and utility ratepayers save a little cash from having better-planned development. And, with a little luck, the county that runs the TDR program might help trim greenhouse gas emissions in the process!

That’s the theory, anyway…and, in fact, our study found that the greenhouse gas reductions are almost certainly real:

Sightline’s analysis of King County’s TDR program and a variety of public data sources suggests that a single TDR exchange could reduce climate-warming carbon dioxide emissions by about 270 metric tons over 30 years, compared with development patterns that might otherwise occur. This is a significant reduction, representing half of the average [per capita] emissions from one US resident for the same period.

Combining energy savings on transportation, electricity, and home heating, we found that shifting a home in the distant exurbs of King County into a compact city or town center can make a real dent in household emissions. And the greenhouse gas reductions were still substantial, even when we assumed that cars and home appliances would grow more efficient over the years.

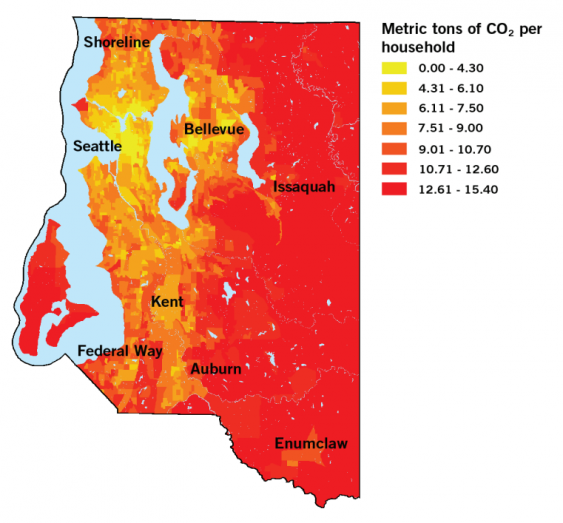

The largest reason that emissions fell in urban areas was that city dwellers drive less. We used two very different models of household transportation energy by neighborhood—based on completely different methods and data sources—and they came to the same conclusion: people in far-flung neighborhoods with few businesses or stores nearby logged more miles in their cars than folks in compact town and city centers. See, for example, this map of transportation emissions in western King County, based on a transportation model from the Center for Neighborhood Technology.

But the devil is in the details. In fact, we looked at some specific cases where King County had used TDRs to boost housing density in areas that were technically inside the urban growth boundary, but still pretty far out in the suburbs. The models we were using showed that some of this new housing would have been associated with even greater transportation emissions than the average King County home!

But the devil is in the details. In fact, we looked at some specific cases where King County had used TDRs to boost housing density in areas that were technically inside the urban growth boundary, but still pretty far out in the suburbs. The models we were using showed that some of this new housing would have been associated with even greater transportation emissions than the average King County home!

So you just can’t say that all TDR transactions automatically reduce emissions. Some definitely do—especially when they boost housing in the yellowest parts of the map above. But some are arguably worse for the climate than doing nothing at all.

What this all points to, in my mind, is that TDR programs can help cities and counties pare back on greenhouse gas emissions. But like any tool, they should be used with care. From the climate’s perspective, using TDRs to boost single-family housing at the urban fringe often represents a wasted opportunity.

Sightline GIS intern Erik Cortes conducted mapping and other analysis for Sightline’s report on Transfer of Development Rights programs.

Comments are closed.