Editor’s Note: The post has been slightly updated on 2/12/12.

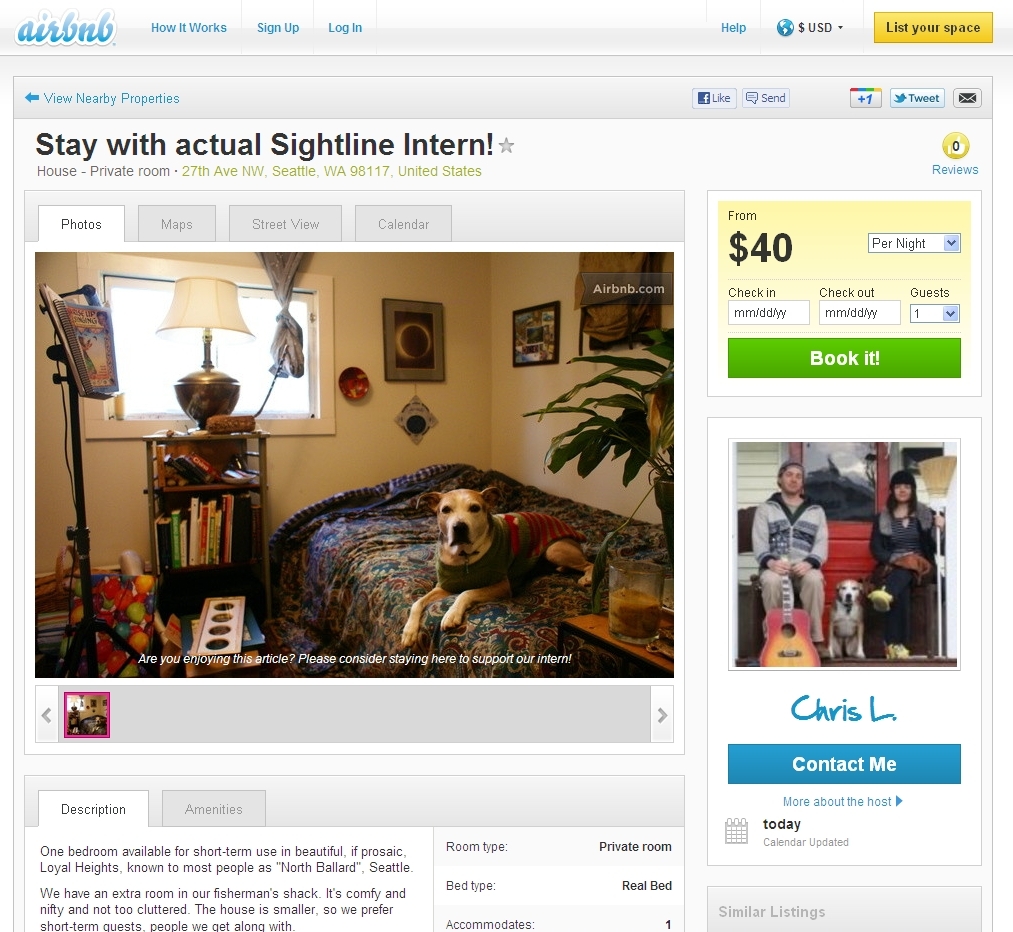

Tight budgets and the internet have given rise to the hottest new thing in travel accommodations. Web-based company Airbnb has received a lot of press recently for its for-profit service that matches travelers with spare bedrooms, such as mine (pictured above). It’s already growing like moss in the Northwest winter, but the potential is much bigger than most have considered. Airbnb and other companies that create a market for guest rooms could fundamentally change the hotel industry, boost income for thousands of householders (including Sightline interns like me!), and slash the ecological footprint of travel.

That is, unless an existing thicket of rules and regulations on the operation of hotels strangles the emerging eBay of empty bedrooms.

Cascadian jurisdictions have yet to crack down on informal hoteling, but authorities elsewhere have. Case in point: New York City enacted a law in May 2011 “banning renting out Class A residential spaces — apartments intended only as permanent, rather than transient, residences — for less than 30 days,” according to the real-estate magazine Real Deal. “The move was prompted, in large part, by complaints from those living next to apartments rented on the website, as well as from the Hotel Association of New York City, a trade group that was concerned about short-term rentals eating into the city’s hospitality business.” Another online source quotes an Airbnb representative arguing that the New York ordinance was not aimed at them at all but at other types of enterprises. Whatever the impetus for the law, though, its effect is to cast a legal shadow, if not a legal net, over peer-to-peer sharing of accommodations. So far, though, Airbnb is still going strong in New York City, with growth clocking in at 35 percent per month since September 2010.

The situation is eerily similar to what happened to Zipcar in the state of Washington in 2007. Zipcar was then the rising star du jour of web-based collaborative consumption enterprises. Out of the blue, the Washington Department of Revenue ruled that Zipcar had to pay the state’s rental car tax—which adds a 10 percent tax on top of the existing state sales tax. The department did this because the rental car companies had been quietly threatening to make a giant stink about unequal treatment. Zipcar and car-sharing advocates did not hear of the tax hike until it was too late to stop it. They were caught flat footed. Since then, Washingtonian car-sharers have never been able to roll back the change, despite considerable effort. Politically, undoing changes is like putting Humpty Dumpty back together again.

Proponents of the fledgling industry of in-home hoteling would do well to anticipate the attacks that the hotel industry will undoubtedly unleash, and may be plotting already. Otherwise, they’ll end up blindsided

After all, Informal hoteling is still in its infancy. In greater Seattle, for example, about 700 different lodgings are now available on a typical night. That’s 2 percent of the 34,459 hotel rooms in the greater Seattle/King County area, and it counts both Airbnb and Couchsurfing.org, the older, free counterpart used by backpack travelers worldwide. If Airbnb is the eBay of guest rooms, couchsurfing is the Craigslist. Greater Vancouver, BC, where housing is so expensive that householders may be especially keen to supplement their incomes, has more informal hoteling than Seattle, with about 800 Airbnb and 700 couchsurfer listings on average nights. Even those numbers do not threaten the formal hotel sector, though. The city has 12,900 hotel rooms in the downtown area alone.

Still, the rapid growth of in-home accommodations could end future growth in hotels. That’s especially true when you consider that much of the Northwest’s existing housing stock was designed for larger families than are common today. One study by Urban Futures in Vancouver, BC, estimated that 29 percent of all homes had more bedrooms than people in them. That’s more than 220,000 empty bedrooms—a massive untapped reservoir of accommodations, already built, painted, furnished, heated (and sometimes cooled), and provided with bathroom and kitchen access. Channeling travel growth into existing homes rather than new hotels would bring big environmental benefits, as Finnish think tank low2no.org argued in an analysis of the carbon footprint of hotels.

Airbnb and Couchsurfing are promising new ventures, yet they are also a return to an older pattern of travel. They have used new technology to resurrect the age-old practice of taking in lodgers and boarders. They are also a simple extension of the still-pervasive pattern of staying with distant relatives, friends, or friends of friends. Just as eBay and Craigslist have given new technological potency to yard sales and flea markets, person-to-person accommodation networks have facilitated the emergence of a larger and more reliable marketplace for informal hoteling.

Yet this green, affordable, and sociable form of housing for travelers is as vulnerable to ill-considered regulation as are car-sharing, hair braiding, and solar clothes drying. Conventional hotels are regulated in special ways under land-use laws (their locations and sizes), building codes (fire safety, structural integrity, handicap access), health codes (especially if they have restaurants), and tax laws (most Cascadian jurisdictions have special taxes on hotel stays, for example). The spare-bedroom market, however, flies under the radar of most such laws at present. Exempting it from hotel-specific regulations makes good sense. Social evaluation tools on collaborative consumption sites such as Airbnb allow a degree of transparency unheard of in prior times, and that transparency obviates the need for as much regulation and public enforcement.

Besides, in the new era of straitened economics, expensive energy, and the imperative of moving beyond carbon, we should be encouraging, not constraining, fuller sharing of existing assets, whether cars or bedrooms. Especially when it lets householders earn a little extra money.

Chris LaRoche is a Sightline Intern, recent MPA grad, and occasional traveler. Learn more about him by staying at his place with Airbnb! Alan Durning edited this post.

Comments are closed.