Permeable pavement can make old-school road engineers and pavement builders anxious. To them, the idea of water seeping through roads like they’re made of Swiss cheese just doesn’t seem right. Water runs off roads, not through them. Or at least it used to.

In the Northwest, there’s a growing acceptance of the use of pervious concrete and porous asphalt for roads, sidewalks, parking lots, and driveways. The unconventional pavement does a great job reducing the amount of polluted stormwater runoff that damages homes, streams and lakes. Instead of gushing from the roads carrying a slug of toxic chemicals, the water seeps through small pores in the pavement, soaking into the gravel and dirt beneath the road. Some of the pollutants get trapped inside or beneath the pavement, or are consumed by organisms living in the ground below it.

Those who’ve used the pavement praise the technology. Advocates can be found around the region, including a 32-acre eco-friendly development near Salem called Pringle Creek, where all of the roads and alleys were built with porous asphalt.

“It’s pretty remarkable to see water disappear into the street,” said James Santana, vice president of Pringle Creek. “We’ve been really impressed with how effective the streets have been.”

The development, which was built in 2007, was deemed “the nation’s first full-scale porous pavement project” by the Asphalt Pavement Association of Oregon.

But fears about the technology persist. Can pavement that’s likened to rice crispy treats to illustrate its pervious nature take a pounding from countless cars, trucks, and buses and survive intact? How long can water seep through it before its pores are clogged with dirt and debris? Is it OK to put a bunch of water underneath a road?

A rice crispy roadway

Permeable pavement has been used for years in the Northwest and even decades elsewhere. A porous stretch of highway in Arizona is more than 20 years old and holding up fine. That’s because permeable roads aren’t that different from a conventional road. Instead of laying concrete or asphalt that’s completely solid, it’s made from a rock and liquid mix that creates a lattice of interconnected pockets of air that allows water to pass through it.

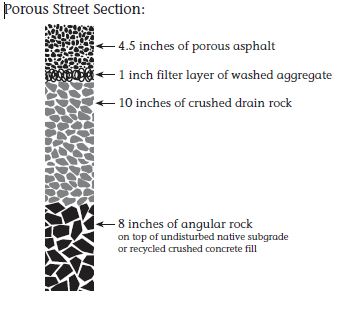

Beneath the layer of concrete or asphalt is a layer, or multiple layers, of gravel that the water can move through. In many cases, this gravel layer can be thicker than it might be for regular, impervious pavement. Underneath that is the native soil. Many experts recommend taking care not to severely compact the native soil and gravel during installation so that these sub-layers remain absorbent.

Some projects also include the use of a geotextile fabric beneath the gravel and on top of the native soil. This material can help maintain the gravel layer and trap pollutants to ensure that they don’t travel into the groundwater, causing contamination. The fabric can also prevent the gravel from settling and causing depressions in the permeable pavement. (This Oregon SeaGrant document gives a great overview of permeable pavement and descriptions of how it’s constructed.)

There are restrictions and limitations to installing permeable pavement. It’s not recommended for use on slopes or in places where the groundwater is very close to the surface. There are still questions and concerns about how much traffic the permeable roads can withstand, and for the most part, it has been used for lower traffic areas such as parking lots, shoulders of roads, pedestrian and biking paths, driveways, and quieter, residential roads.

But experienced engineers say that abundance of caution regarding low traffic is overkill. Mark Palmer, city engineer for Puyallup’s Public Works department, points to the lasting success of the Arizona highway to make his case.

“I really don’t have a problem,” using permeable pavement on high traffic roads, he said. “But to be realistic, we have to take baby steps to get people convinced (that it works).”

While Pringle Creek is a residential area, Santana says there are a lot of heavy trucks driving through the community during build-out and construction, and the streets show no signs of wear or damage.

Other examples of permeable pavement in the Northwest include:

- Rainier Avenue, a two-lane street with two additional parking lanes in Issaquah, in the foothills of the Cascades.

- Multiple projects in Bremerton including parking lanes on Pacific Avenue in the city’s downtown; the shoulders of a heavily-used road in South Kitsap Industrial Area; sidewalks and parking areas in Lions and Blueberry parks; Schley Boulevard in the East Park military housing development; and Sylvan Way Meadows, a private housing development. Other projects using porous asphalt are being planned.

- Gresham, a neighbor of Portland, installed wide strips of porous asphalt along Holladay Street in 2007, making it the city’s first “green street.” City code strongly encourages the use of permeable pavement and other applications can be found around Gresham.

- A 32,000-square-foot roadway in Snohomish County’s city of Sultan was one of Washington’s first uses of permeable pavement in a public right of way when it was installed in 2006. The project, located in a 20-home development called Stratford Place, also included driveways and sidewalks.

- Dockside Green, a 15-acre redevelopment project that’s being built in Victoria, BC, will use permeable pavement for most of its hard surfaces.

- Portland has lots of projects using permeable pavement, beginning with a 2004 installation on residential streets.

- Washington State University is doing research to better quantify the performance of porous asphalt and to understand what happens to pollutants. The work is being done at the Washington Stormwater Center at WSU’s Puyallup campus.

I can pave for miles and miles

There are endless opportunities to use permeable pavement in lieu of conventional road construction in cities and towns across the Northwest.

In Seattle alone, 400 miles of major roadways need repairs, and many streets are in such bad shape that they need to be reconstructed, according to statements made this fall by the city’s transportation department.

But the city so far has been disinclined to use porous asphalt on busy streets. And to be fair, the Northwest has seen some problems with the technology. Seattle itself ran into trouble with some permeable pavement that was laid in West Seattle. After it was installed, a cement mixer used for an unrelated project rinsed out its equipment onto the pavement, clogging the pores and requiring some of it to be replaced.

In Bremerton, cars were allowed to park on a stretch of porous asphalt on Pacific Avenue before it had sufficiently cooled and set, causing some of the asphalt to sheer off the top. Despite the damage, the blacktop is still soaking up water and perfectly useable for vehicles.

“There’s just a little bit of unsightliness to it,” said Larry Matel, former managing engineer for Bremerton’s Public Works & Utilities overseeing stormwater projects.There was “a little bit of trial and error” in figuring out how long to wait before the road was ready for traffic.

Similarly, Puyallup’s Palmer oversaw the construction of porous asphalt cul-de-sacs in a development in the town of Rainier. The streets experienced some “spalling” in which some of the rocks in the asphalt crumbled out of the road. Palmer said the road, which was built in about 2004, needed a higher amount of asphalt to make it adhere better. And again in this case, the street is still performing well.

“It’s more of an aesthetic issue,” Palmer said. The spalling was mostly a problem in places where cars are parking, torquing their wheels and digging into the asphalt.

Putting a stop to potholes?

Keep in mind conventional roads fail everywhere, all the time. Again, one can look just about anywhere in Seattle to find a street pocked with potholes and other roadway hazards.

There’s a strong case to suggest that permeable roads could and should hold up better than traditional ones. Most often, the pervious roads are built with a thicker subbase of gravel and frequently the asphalt or concrete are deeper as well.

“You’re putting a stronger pavement down, so you’ll have a more durable lasting pavement,” Palmer said.

Palmer said that many conventional roads in Puyallup have a tendency to “alligator” or break into scalelike chunks because the water table is high and the water soaks the asphalt, causing it to fail. There are plans to install porous alleys in Puyallup and a porous residential street.

In Seattle, the roads in the city’s northend tend to get the most potholes, said Steve Pratt, street maintenance director for the city. He explained why in a 2011 story in the Seattle Times:

“Basically they paved asphalt on dirt, with no gravel subbase.” Instead of draining, stormwater forms puddles beneath the blacktop, he said.

But if the road was rebuilt to add a thicker layer of gravel so that the city wasn’t returning add nauseam to patch the potholes, it could be capped in porous asphalt and the problem solved.

Another worry with the permeable roads is that the pores will get blocked with sand and dirt, or even as happened in Seattle, with a foreign source of concrete. If the holes get clogged, water will sheet off the pavement as it would with a normal road, creating the stormwater problems it was meant to resolve.

Experience, however, shows that a little extra maintenance up front can prevent clogging. At the Pringle Creek development, they lay geotech fabric on the street in front of new construction to catch the mud and dirt that trucks can track off a site. Builders and landscapers are cautioned not to dump dirt or sand in the street. They blow and removed the leaves that fall in autumn. And once a year, they hire a truck to vacuum their roads. It costs about $200.

“We use a standard vacuum truck that cleans all the (parking lots at) Walmarts in America,” said Santana. “It’s not special equipment.”

Even if maintenance is less than stellar there are more extreme solutions to choked pavement. One expert recommends something called the BIRD (Bunyan Infiltration Restoration Device) from Bunyan Industries that blasts damaged pavement with water and then vacuums out the debris. The machine is reportedly able to restore permeability to surfaces clogged with concrete grindings, sawdust, and asphalt.

Porous asphalt and pervious concrete do present some unique challenges in installation and maintenance.They take more thought and planning than standard roads, and perhaps more sweeping or vacuuming. But when done right, they work well. And when you consider the damage caused from the polluted stormwater runoff that gushes from conventional roads and parking lots, it’s hard to make the case that they’re doing the job we need them to do.

Permeable roads have proven to be an effective solution in countless situations. In addition to the benefits to stormwater, the pervious roads are quieter and reduce the risk of hydroplaning and water splashing onto windshields.

Because the pervious roads are thicker, they require more materials and often cost more to install. But in fact, they can actually save cash. In Pringle Creek the porous asphalt took the place of costly, conventional stormwater drainage systems that shunt water to detention ponds or straight into creeks.

“We saved a tremendous amount of money not having to do pipes and gutters and curbs,” said Santana. That sort of concrete work is very expensive and maintenance adds up as well.

“Our streets are our pipe and drain system,” he said. “We’re really pleased with the results.”

Comments are closed.