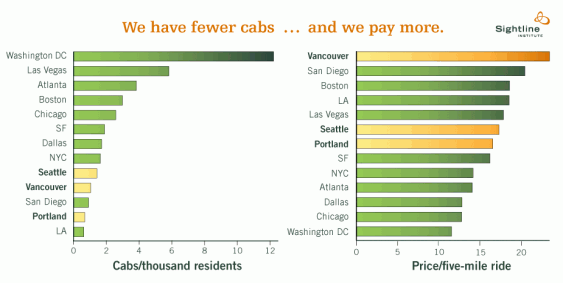

Update 8/11: I have an addendum to this post published here. Also, the chart was altered to reflect a slightly higher number for Vancouver.

What if the Northwest’s cities legally capped the number of pizza delivery cars? What if, despite growing urban population and disposable incomes, our Pizza Delivery Oversight Boards had scarcely issued new delivery licenses since 1975? Pizza delivery would be expensive and slow; citizens would rise up in revolt.

Substitute “taxicab” for “pizza delivery” and you have a reasonable facsimile of the taxi industry in Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver, BC: tightly restricted taxi numbers, high fares, and low availability.

Plentiful, affordable taxis facilitate greener urban travel. They help families shed second cars, ride transit more often, and walk to work on could-be-rainy days. They fill gaps in transit systems and provide a fallback in case of unexpected events.

In the Northwest’s largest cities, however, local ordinances enforced by taxi boards suppress the entry of new cabs onto the streets. They impose arcane and ultimately farcical management principles reminiscent of Soviet planning. Imagine teams of pizza regulators pawing through discarded receipts and pizza boxes to determine whether demand for pizza delivery markets are “oversaturated,” and you won’t be far from the truth. Restricting taxicab licenses undermines passengers’ mobility, local economies, and—by encouraging driving—our natural heritage; uncapping cabs would allow market competition to bolster all three.

As shown in the figure above, at present, the Northwest’s largest cities have fewer cabs per capita, and higher fares, than many US cities. Seattle’s 1.4 cabs per 1,000 residents is twice Portland’s 0.7, and well above Vancouver’s 1 cab per 1,000. But all our cities lag. Washington, DC, has more than 12 cabs per 1,000 residents; Las Vegas has almost 6; and San Francisco has 2. Meanwhile, the cost of a typical, five-mile trip is $16.50 in Portland, $17.25 in Seattle, and $23.39 in Vancouver. Washington, DC’s typical fare is just $11.50.

Consider the efforts of Portland’s Transportation Board of Review, which has the power to issue new taxi licenses but is also charged by city law with monitoring “market saturation factors.” It is supposed to avoid market oversaturation, something every other market—from pizza delivery to home remodeling—manages to do just fine on its own, without benefit of a board. In Portland, the rules actually require applicants to prove that a new taxi license is needed. Imagine if Pizza Hut had to demonstrate to the Pizza Delivery Board that it needs another driver for the Super Bowl.

In Vancouver, the Passenger Transportation Board‘s rules are slightly more flexible than Portland’s. They have allowed a trickle of new cab licenses over the years, but they have screened out many applicants, too. A Vancouver cab company seeking a new license is supposed to prove the taxi market isn’t already too full, and that can be a complex question to answer. In other markets, entrepreneurs figure out the answer to their own satisfaction, then see if they’re right by risking their own time and money. New pizza parlors do not have to show city regulators that their delivery service is needed.

Worse, in Vancouver, cab companies may petition against a competitor’s new license. When Pizza Hut applies for an extra delivery license for the Super Bowl, in other words, Domino’s has a right to challenge the application. In 2010, the board rejected some 43 percent of requests for new permits, despite the city’s high taxi fares and paltry cab numbers.

Seattle’s Department of Executive Administration, like taxi boards to the north and south, tries to divine the number of taxicabs Seattle can support without oversupplying the market (whatever that means). Its method is to comb through an enormous database of “weighted average taxi response times” to look for signs that wait times are getting worse. Making the heroic assumption that Seattle’s status quo of long waits and fruitless cab hunting are acceptable, it looks for signs of further deterioration before considering new licenses.

A better test would be whether anyone is willing to pay for a taxi license. Guess what? Seattle medallions currently trade for $100,000, when they’re for sale at all. When the city offered 15 new licenses for wheelchair accessible taxis in 2009, 723 drivers applied. Vancouver taxi licenses have sold for up to CDN$500,000. (In New York, taxi medallions were selling for close to $1 million in June.) The explanation of these bubble-like prices is economics: restricting taxi supply increases the profitability of each cab. Holders of taxi licenses can fill their cabs more of the time and keep the meter running.

In the Northwest as across the continent, taxi regulation is dominated by license caps and fixed rates, but that isn’t the only way. Washington, DC, has no limit on the number of cabs. It has plenty of taxis and low prices. The capital city does regulate taxis, insisting, for example, that drivers and vehicles meet safety criteria, that fares be clearly posted, and that meters be accurate. But DC law imposes no lid on taxi licenses. That’s good sense. When we import that approach to Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver, we’ll have more-robust urban taxi fleets and we’ll be able to leave our own cars home more of the time.

Guest blogger Vince Houmes of Seattle is a longtime Sightline supporter and hobbyist policy researcher.

Sources of charts: Data from the Chicago Dispatcher, with updated city populations (from Wikipedia) and updated numbers of Seattle and Vancouver taxis. An “average trip” is 5 miles long, with 5 minutes of waiting. Per-capita numbers are for city, not metro, population. Vancouver cab prices relied on an outdated website when this post was first made. Correct prices may be found here.

Sightline’s Making Sustainability Legal project identifies specific regulatory barriers to affordable, green solutions. If you’ve come across such an obstacle, please let us know by writing Eric (at) Sightline (dot) org.

Comments are closed.